In a space that’s free of investment screening tools and fraught with cautionary tales, mergers and acquisitions require careful attention to detail. Using case study examples, Investment Analyst Irena Petkovic highlights how her consolidator checklist fits within Burgundy’s investment process and sheds light on what makes a consolidation strategy prosper or crumble.

One of the first things I was taught in business school was the pattern of failed acquisitions. Professors would often regale their students with cautionary tales of mergers and acquisitions (M&As) gone wrong, and there seemed to be endless examples of value destruction.

When I entered the investing world, I was surprised to find that not only are acquisitions common, but these “consolidators” make up some of the most successful investments. Rather than engage in the occasional transaction, these companies rely extensively on acquisitions for growth. Many of Burgundy’s successful investments across our regional portfolios have been in consolidators, including Alimentation Couche-Tard, Constellation Software, First Service, SS&C Technologies, and Diploma to name a few.

Despite the success stories, academia’s concerns are still warranted. Some of the worst stocks of all time have also been consolidators. Valeant, Toll Holdings, U.S. Office Products, and Slater & Gordon are some names that have endured a great deal of value destruction. In fact, research has shown that more than two-thirds of consolidation strategies have failed to create value.1

What is it about a consolidation strategy that makes them either work so well or unravel so spectacularly fast? The answer is in the unglamorous practicalities of buying and integrating companies. Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) who feel pressure to continue growing start overpaying for acquisitions, salespeople leave over disagreements around compensation, computer systems do not talk to each other, and people simply do not get along. These tedious details can make or break a consolidation thesis, and they are almost impossible to predict.

This wide range of outcomes creates opportunities for active managers like Burgundy. It is impossible to run a filter for new ideas that sorts the good consolidators from the bad, and underlying profitability can be difficult to untangle. Since revenue and earnings grow non-linearly (which makes them inherently awkward to model), growth via acquisition is also difficult to predict. Investing in a consolidator also requires outsized conviction in the chief capital allocator, a role often assumed by the CEO of companies who have adopted this business model,2 and management meetings help tremendously in understanding the individual’s vision, acumen, and temperament.

From analyzing numerous consolidators, Burgundy has come up with a “consolidator checklist” to help us separate the good from the bad. The five characteristics in the checklist include: (1) operating in a fragmented industry, (2) experiencing high customer retention, (3) showing evidence of real synergies, (4) having a strategic financing strategy, (5) having a well-aligned capital allocator.

“From analyzing numerous consolidators, Burgundy has come up with a ‘consolidator checklist’ to help us separate the good from the bad.”

While this checklist is a useful tool, it is important to recognize that it is not used in isolation. At Burgundy, we also incorporate our own deep research process. By applying five of the most important characteristics of a successful consolidator, showcasing two unsuccessful case studies, and sharing how Burgundy adds our own judgement and research, we hope to offer some insight into this universe and demonstrate the speed at which seemingly great consolidators can implode.

THREE BURGUNDY PORTFOLIO CONSOLIDATORS

1 – FRAGMENTED INDUSTRY WITH LITTLE COMPETITION FOR TARGETS

One of the first things we consider is whether there is a long enough runway for the company to deploy capital at attractive prices. There are very few targets if the consolidator operates in a concentrated market. Competition can also push up prices, which decreases returns on capital.

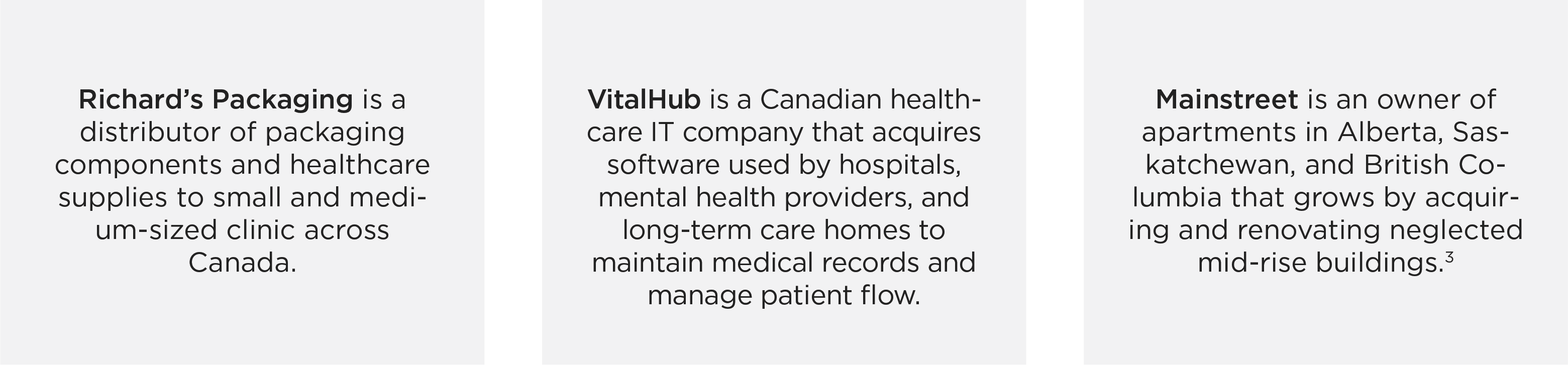

One of the ways consolidators can minimize competition for acquisitions is by focusing on smaller targets. For many companies in the Canadian small-cap universe, it can be meaningful to acquire a company that would be considered too small for a private equity fund. For instance, VitalHub focuses exclusively on prospective targets with $1-12 million in revenue,* which would be significant to the $28 million in revenue they have generated over the last 12 months. Stretching across Canada, Europe, Australia, and the United Kingdom, VitalHub’s management team has identified more than 400 companies that could be possible acquisition targets.

To avoid paying high prices, Richard’s Packaging also focuses on smaller targets and looks for companies generating between $20-100 million in revenue. Unlike its competitors, who focus on larger acquisitions that can cost up to twice as much, concentrating on acquiring smaller companies allows Richard’s to not only realize the same synergies as its competition, but (with an estimated 50 distributors of this size in its markets) also have access to a long runway.4 Likewise, Mainstreet Equity focuses on purchasing mid-market apartment buildings with less than 100 units. Ownership of these buildings is highly fragmented among mom-and-pop operators, with the 10 largest apartment owners in Canada owning just 12% of total supply. Since smaller owners are often capital constrained, there is also the opportunity to add value through renovations in this segment. This combination of highly fragmented ownership and assets which have been under-invested in allows Mainstreet to purchase apartments below replacement cost.

Each of these companies operates in industries in which acquisition activity has been increasing over time and competition for assets has intensified. However, as described above, the management teams of these companies have cleverly carved out niches to minimize competition and remain disciplined in the face of valuations rising around them.

2 – HIGH CUSTOMER RETENTION

As previously mentioned, integration can be the undoing of an otherwise high-potential consolidation strategy. One way to increase the likelihood of a smooth integration is to acquire in industries with sticky, recurring revenues to begin with. If it is difficult for a customer to switch away from the target’s solution, the customer will be less sensitive to changes in ownership and may be more tolerant of any operational hiccups. This is the case with VitalHub, which seeks to acquire businesses where more than 60% of revenues are recurring software subscription fees. The clinicians who make up VitalHub’s customers use the software every day, and it often provides them with real-time insights into bed utilization and patient flow. Switching software would be disruptive to patient care and would require re-training staff. This dynamic has kept churn rates at VitalHub in the low single digits.

Similarly, while Richard’s Packaging’s revenues are not contractually recurring, customers would face disruption if they switched. Richard’s focuses on distributing to small and medium-sized businesses (SMBs) that do not have a full procurement team and rely on Richard’s for logistics management. This means that Richard’s holds inventory at distribution centres near customers and provides just-in-time delivery. Unlike larger customers who may have their own warehouses, customers switching from Richard’s risk going without packaging and being unable to sell their products.

3 – EVIDENCE OF REAL SYNERGIES

We look for evidence that the consolidator can add value to the target company and that those synergies are not only repeatable over several acquisitions, but also sustainable long term. Cost synergies, where operating expenses can be reduced, are the most common and reliable source of synergies. Examples include reducing the acquired workforce (there is seldom the need for two human resources departments, two information technology departments, two accounting teams, etc.), renegotiating supplier agreements, and closing redundant facilities. We recognize that these cost synergies, while highly coveted by investors, often mean employees are losing their jobs. Indiscriminate workforce reductions in the name of short-term profits can be unsustainable long-term, and we place a high level of importance on determining whether management is cutting too deep.

VitalHub has consistently been able to reduce the costs of acquired companies by over 20% by offshoring research and development to an office in Sri Lanka. As a result, VitalHub can take a target from breakeven to 20-30% earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) margins in short order.

Similarly, Mainstreet’s acquisition model results in cost synergies at both the capital investment and operational expense level. When investing in a building’s renovations, Mainstreet can do so for 40-50% less than its competitors. This is because Mainstreet transacts in volumes large enough to source materials directly, without the use of a distributor, and has built these relationships over 20 years. Mainstreet is also able to lower operating expenses by clustering apartment buildings within a five-block radius, doing away with the need for resident managers and property managers at each building.

Conversely, revenue synergies assume that the combined entity will have higher sales growth than if the companies were separate. This increased sales growth can come from cross-selling, gaining access to new distribution channels, or increasing brand recognition from being a larger company. The focus on serving SMBs provides a benefit to bundling and simplifying purchasing, which has made Richard’s Packaging successful in cross-selling across its network. VitalHub has also been successful in cross-selling acquired technologies to existing customers. This is especially true in its patient-flow segment since hospitals prefer to work with existing suppliers.

“How a company acquires is just as important as what is acquired. As investors in the acquirer, we are conscious of whether acquisitions are financed with per-share earnings in mind.”

4 – STRATEGIC FINANCING

How a company acquires is just as important as what is acquired. As investors in the acquirer, we are conscious of whether acquisitions are financed with per-share earnings in mind. The best consolidators find a way to finance acquisitions that do not rely on dilutive equity issuances or excessive debt burdens. Similarly, the operational risk involved with consolidation means that excessive leverage can magnify the downside. Both VitalHub and Richard’s Packaging have clean balance sheets and do not rely on debt when acquiring. Richard’s total shares outstanding have decreased over the past decade as management has used excess cash to buy back shares.

Mainstreet Equity has found a creative way to finance acquisitions in a non-dilutive way. Mainstreet’s financing strategy requires very little equity, which is different from a typical REIT. When Mainstreet acquires an apartment building, the company uses cash and a line of credit to buy it outright. When renovations are completed, Mainstreet has the apartment appraised. This appraisal is used to take out a lower-rate, government-insured mortgage with Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), the value of which often exceeds the initial purchase price and construction costs. This frees up the initial cash to repeat the process with another property, meaning there is virtually no additional capital required. This shows up in Mainstreet’s capital structure, with total shares outstanding decreasing by 15% over the past decade and funds from operations (FFO) per share compounding at 17%.

5 – A CAPITAL ALLOCATOR WITH A DISCIPLINED APPROACH AND STRONG ALIGNMENT

An investment thesis based on capital allocation places outsized emphasis on the allocators themselves. We look for evidence of strong capital allocation acumen with CEOs of consolidators, a clear succession plan, and incentives that emphasize long-term earnings growth over “empire building,” where revenue growth is the only key performance indicator (KPI).

The most observable way to determine alignment is insider ownership, and both Richard’s Packaging and Mainstreet have CEOs with significant stakes in their businesses. Gerry Glynn, the CEO of Richard’s Packaging, has been with the company since 2002 and owns nearly 20% of shares outstanding. Similarly, Mainstreet’s CEO Bob Dhillon owns 46% of total shares outstanding and still does most of the acquisition sourcing and diligence himself.

Considering the importance of the CEO to the overall thesis, consolidators should also consider board composition. Several of VitalHub’s board members have M&A experience in healthcare, and many have sizable positions in the company. This suggests there is both strong alignment and experience.

BLOW-UP CASE STUDIES

Recognizing the signs of a good consolidator is not enough. Even with many positive indicators, too many red flags can lead to an ugly undoing.

CASE #1: VALEANT PHARMACEUTICALS

Valeant was a specialty pharmaceutical company based in Quebec. In 2008, Valeant hired Michael Pearson, a new CEO who shifted the strategy away from traditional drug manufacturing to growth by acquisition. A lot of Pearson’s strategy made sense in theory. He believed that since the company had to invest heavily in research and development (R&D) to develop new drugs that may or may not be successful, the returns on capital were too low for a traditional drug manufacturer. Acquiring commercial drugs would allow them to cut R&D and rapidly expand the product portfolio.

The strategy was hugely successful. By 2015, Valeant was the most valuable company on the S&P/TSX Composite Index, eclipsing the Royal Bank of Canada. Under Pearson’s leadership, Valeant’s stock price had risen more than 4,000%, and “smart money” piled into the stock. The company was revered for its insider alignment, it had hundreds of small drug companies globally, and 80% of Pearson’s compensation was tied to stock options (versus 50% for the median S&P 500 Index CEO), and those options vested exponentially based on share price performance. If Valeant stock returned more than 60% each year for three years, the number of options that would vest would be four times the number than if it only returned 15-29%. Additionally, Pearson would receive zero if annual returns were under 15%. Valeant proved that more alignment is not always a good thing. In this case, being so torqued to the share price meant Pearson was incentivized to be extremely aggressive. (Due to concerns around the sustainability of its growth strategy and its reliance on external capital instead of internally generated cash flows for funding, Burgundy never owned Valeant.)

In October 2015, just two months after becoming the most valuable company on the S&P/TSX Composite Index, Valeant’s decline began. Several reports emerged detailing the relationship between Valeant and Philidor, a specialty pharmacy that sold Valeant’s drugs. These reports showed that Valeant secretly controlled Philidor and used it to increase sales. These claims were the tipping point for Valeant. Within six months, the share price declined 90%, from $230 to $30. From its peak valuation to its price today, Valeant has destroyed $65 billion in shareholder value.5

“In October 2015, just two months after becoming the most valuable company on the S&P/TSX Composite Index, Valeant’s decline began.”

Rapid Pace of Acquisitions & Overpaying

Over Pearson’s eight-year tenure, Valeant made 120 acquisitions. Pearson prided himself on getting deals done fast. In 2013, he told The Globe and Mail that due diligence happens “very quickly,” sharing that the work for a US$2.6 billion acquisition was completed in just 10 days.6 Revenues grew from US$757 million in 2008 to US$9.7 billion in 2016. To keep growing, Valeant had to keep buying.

By 2013, Valeant’s reputation as a “serial acquirer” was widely known by pharmaceutical companies, and they increased their expectations accordingly. When Valeant acquired Bausch & Lomb in 2013, 95% of the purchase price was accounted for as goodwill, which is the excess purchase price over the fair value of assets acquired. In 2015, Valeant purchased Salix for US$15.8 billion. One year later, Valeant unsuccessfully tried to sell the company for US$10 billion. A company source said that “Pearson overpaid for Salix by something like six or seven billion dollars.”7

Unsustainable Synergies

Once Valeant acquired a drug maker, the company would quickly reduce costs, mainly by slashing R&D. Valeant spent 3% of revenues on R&D versus 15-20% for a typical drug maker. While evidence of synergies is one of our five characteristics, these synergies must be enduring. Cutting R&D expenditure to this degree meant that there were no new drugs being developed. To maintain growth, Valeant had to constantly be acquiring.

This also meant that Valeant had to extract as much profit as possible from the drugs the company purchased before they were genericized. Valeant did so with indiscriminate and highly controversial price increases. In 2015 alone, the company increased the prices of 56 drugs, representing 81% of its portfolio, by 66%.8 Prices more than quadrupled. A 2015 study found that of drugs whose prices had risen 300 to 1,200% over the past two years, half of them belonged to Valeant.9 Pfizer, by contrast, raised prices on 51 drugs by an average of 9% in 2015 and by 15% at most.10

Healthcare has always been political, and it was not long before Valeant’s pricing strategies drew criticism from Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, and other members of U.S. Congress. Valeant was subpoenaed by U.S. prosecutors in October 2015 to investigate its drug pricing and distribution strategies and was separately investigated by both the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate.11

Highly Levered

Valeant relied largely on debt to finance its acquisition strategy. From 2008 to 2016, debt ballooned from zero to US$30 billion, which represented 7.2 times its EBITDA. This financing strategy was not sustainable. As Valeant’s drugs came off-patent and faced competition from generics, the company did not have the cash to invest in R&D to create new drugs or to do further acquisitions. Valeant was paralyzed.

CASE #2: THE LOWEN GROUP

The Loewen Group was a consolidator of funeral homes and cemeteries in North America. In 1979, Ray Loewen began noticing that many aging funeral home operators in his town were struggling with succession. Loewen recognized this as an opportunity, and he began acquiring funeral homes across Canada, eventually raising capital in an initial public offering (IPO) in 1986.

On the surface, Loewen had several of the characteristics of a strong consolidator. The funeral home and cemetery industries were highly fragmented, with 89% of funeral homes and 93% of cemeteries in North America being owned by families in 1996.12 Despite this, Loewen Group was bankrupt by 1999.

The company’s decline began in 1995 after a jury ordered the company to pay US$500 million in damages to a funeral home operator who accused them of reneging on an agreement to purchase two of his homes. While the settlement was ultimately negotiated down to $165 million, it set off a domino effect. By 1999, the company had earned the title of worst-performing stock of the year, trading down 93% to US$0.17. Loewen Group’s share price peaked at US$55.50 in 1995.13

Rapid Pace of Acquisitions & Overpaying

After the IPO in 1986, Loewen Group planned to spend US$14 million on acquisitions in 1987, and then US$10 million and US$4 million in the next two years.14 However, the company never slowed down. Loewen had 20 funeral homes in 1985 and 131 by 1989. In just one year, that doubled to 266 homes. In five years, this would almost quintuple, with Loewen exiting 1995 with 1,115 funeral homes and 427 cemeteries.

To maintain this frenzied growth, Loewen had to buy as many homes as possible as quickly as possible. This led to overpaying, with analysts at the time estimating that Loewen was paying 20-100% above fair value for properties.

Straying from the Core

As investors came to expect high growth rates and analysts began writing about the “golden era” for the death industry, Loewen was pressured to continue growing earnings by more than 30%. This led Loewen Group to stray from its core operations and begin acquiring cemeteries, which were not as profitable as funeral homes. By 1998, cemeteries represented 40% of revenues, versus 15% in 1994.

Minimal Synergies and Integration

The purchasing behaviours of customers at funeral homes is different from most industries. Bereaved family members rarely care about brand and often seek out a locally owned home. This preference was so strong that some homes Loewen acquired would keep their new ownership secret. To illustrate just how localized these funeral homes remained, consider that when Ray Loewen stepped down as CEO in 1998, his successor discovered 1,300 separate corporate entities when he took over.

Price Increases Gone Too Far

Like Valeant, price increases featured prominently in Loewen’s acquisition strategy and was one of the only levers the company could pull to generate returns. However, Loewen took these price increases too far, preying on the vulnerability of grieving families. Loewen changed the names of its lower-cost services to shame families, with the lowest cost casket being named the “welfare casket” and a cremation being termed a “basic disposal.” This ruined the funeral home’s reputation, and in 1998, Loewen reported that its homes had conducted 5% fewer services than in the prior year. One industry expert explained it as follows: “They charged too much and pushed to the point where the public wouldn’t take it anymore.”15

High Dilution and Leverage

Loewen Group raised equity every year from 1988 to 1994, with the share count more than tripling. This meant that despite net income growing by more than 10 times over this period, earnings per share had not kept pace, having only grown four times. Loewen also relied heavily on debt, meaning those earnings were being unsustainably propped up by an increasingly leveraged balance sheet. At the time of Loewen’s bankruptcy in 1999, its debt reached US$2.3 billion, a load borne by a mere US$117 million in EBIT (earnings before interest and tax) in 1998.

PUTTING A CHECKLIST INTO PRACTICE

While our consolidator checklist lays out a neat wish-list of characteristics, determining whether a company possesses them often requires some creativity. Many of the characteristics laid out in this piece are not easily observable in a company’s financial statements, especially if the consolidator is in its early innings. Things like poor customer retention, unsustainable cost-cutting, and poor systems integration can all be buried beneath a heap of successive acquisitions, and it is not until the acquisitions stop, and it’s too late, that a broken consolidator reveals itself.

At Burgundy, our research tools allow us to go beyond filings and get on the phone with customers, former employees, industry experts, and competitors. These conversations help us round out our thesis and, in many cases, have revealed red flags that we never would have seen otherwise. We also use these conversations to inform discussions with management teams, many of whom we meet several times before investing. This process allows us to untangle the company’s own consolidator checklist and determine whether it makes for a high-quality, enduring company or one that is breakable at best.

* All dollar amounts and references to returns are in Canadian dollars, unless otherwise specified.

1. https://www.inc.com/melissa-schilling/the-top-4-reasons-most-acquisitions-fail.html

2. The chief capital allocator is the individual tasked with making the final decisions on how to invest the money a business

has available to it in order to grow the value of the operation. While this person is often the CEO, the CFO or another senior-

level individual may also assume this position.

3. Note: Richard’s Packaging, VitalHub, and Mainstreet Equity are current holdings in the Burgundy Canadian Small Cap Fund.

4. Based off Richard’s Packaging’s estimates

5. In July 2018, Valeant Pharmaceuticals changed its name to Bausch Health Companies Inc.

6. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/rob-magazine/how-valeant-became-canadas-hottest-stock/article8889241/?

page=all

7. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/rob-magazine/inside-story-valeant-pharmaceuticals-fall/article34432530/

8. Valeant Pharmaceuticals: Eroded Reputation and Stock Price – Ivey Publishing

9. https://sevenpillarsinstitute.org/valeant-pharmaceuticals-case/

10. Valeant Pharmaceuticals: Eroded Reputation and Stock Price – Ivey Publishing

11. Valeant Pharmaceuticals: Eroded Reputation and Stock Price – Ivey Publishing

12. TD Securities, 1996

13. While Burgundy we did hold shares of common stock in Loewen Group in our Canadian equity strategies in 1997, we exited

a year later

14. Billion Dollar Lessons

15. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1999-oct-24-fi-25679-story.html

Source: Burgundy research, company filings, the Atlantic, BBC Ideas.

This post is presented for illustrative and discussion purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment advice and does not consider unique objectives, constraints or financial needs. Under no circumstances does this post suggest that you should time the market in any way or make investment decisions based on the content. Select securities may be used as examples to illustrate Burgundy’s investment philosophy. Burgundy funds or portfolios may or may not hold such securities for the whole demonstrated period. Investors are advised that their investments are not guaranteed, their values change frequently and past performance may not be repeated. This post is not intended as an offer to invest in any investment strategy presented by Burgundy. The information contained in this post is the opinion of Burgundy Asset Management and/or its employees as of the date of the post and is subject to change without notice. Please refer to the Legal section of this website for additional information.