Investment Analyst Irena Petkovic invites us into her first year at Burgundy, which happened to coincide with the year of COVID-19. In this exploratory piece, Irena delves into the world of Canadian real estate investment trusts, where she offers perspective on these tumultuous times and considers what the future of the industry may hold.

On March 16, 2020, the Toronto Stock Exchange tripped a circuit breaker for the third time in eight days. Circuit breakers are emergency measures where trading is temporarily halted to give investors time to calm down and prevent markets from entering freefall. Rather than offer a meditative pause, however, these halts felt like 15 minutes of “airtime,” the term that roller coaster enthusiasts use to describe the feeling of terror, excitement, and weightlessness when going over a hill.

I joined Burgundy only nine months earlier, taking the role of Investment Analyst on the Canadian small-cap equities team. Prior to this, I spent my free time reading lessons from value-investing greats who mused on the potential bargains awaiting discerning investors during an indiscriminate selloff. By reading about it, I naively believed I would have the fortitude to invest deftly in my first meltdown, which I presumed would be in the very distant future. I did not expect to see a bear market unfold with frightening speed within my first year.

One of the first companies I worked on was NorthWest Healthcare Properties REIT. Real estate investment trusts, or REITs, are companies that hold portfolios of real estate and distribute most of their free cash flow as dividends. Since most REITs do not offer significant returns over their dividends, we had a small real estate portfolio at the time. Occasionally, REITs will have distinct assets that enable them to meet our return expectations. With its portfolio of healthcare real estate, we believed NorthWest was one of these, and we bought the company at the end of 2019. I will return to NorthWest later.

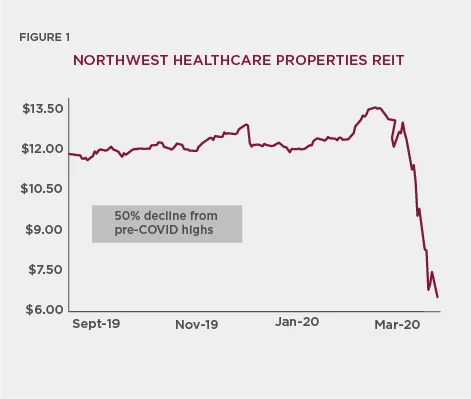

The trading halts did not have their intended effect, and the market went back into freefall for another week. NorthWest was taking a beating again. My stomach lurched as I studied the share price chart. Figure 1 indicates what I saw:

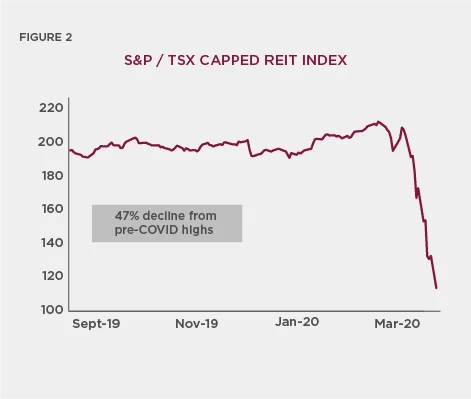

When I pulled up the S&P/TSX Capped REIT Index, a barometer of the Canadian REIT industry and subindex of the S&P/TSX Income Trust Index, it revealed a similar pattern, as demonstrated in Figure 2:

Investors concerned about the prospect of empty office buildings and closed malls were left asking questions that were previously unthinkable. Would the office market ever come back if work from home became broadly accepted? Would retailers pay their landlords if malls were closed? I was forced to consider similar questions for NorthWest. I wondered whether hospitals would be able to pay rent if elective surgeries were cancelled.

Shortly after, NorthWest reported that 93% of April rents had been collected. The lurching feeling eased a little. It looked like the company would survive, though I was sure there would be more surprises to come. The aggressive central bank response triggered by COVID-19 was also welcome news for REITs, with two emergency rate cuts lowering interest rates by 1% in March. This reduction benefitted REITs because real estate requires the use of debt, and interest is often a REIT’s largest expense. These fundamentals were not reflected in share prices, with the REIT market down 24% halfway through 2020 and only the energy industry doing worse. This was puzzling. Some REITs had close to pre-COVID-19 levels of revenue and had a major expense tailwind coming from lower interest rates. The confusion grew as our team began hearing from private real estate investors that competition for assets was intensifying and private market prices were exceeding pre-COVID-19 levels in some asset classes. It quickly became clear to us that public markets were pricing all REITs as if they were offices and malls.

Our team set to work sifting through the rubble. We conducted 15 calls with REIT executives and five calls with real estate lenders. We attended three conferences virtually and spoke to half a dozen experts, ranging from brokers to developers. Most importantly, we observed our own neighbourhoods. Grocery stores thrived, packages became a permanent fixture of front porches, and home purchases continued. After speaking with management teams from across the country, we also came to appreciate the importance of having long-term focused executives, especially when navigating a downturn. We had the immense privilege of learning about and speaking to many of these managers, and our REIT holdings today have some of the highest levels of insider ownership in our portfolio, averaging 19%.

Our research identified four trends that COVID-19 had accelerated: e-commerce, immigration, low interest rates, and the institutionalization of real estate. These trends gave us the confidence to add to our position in NorthWest and initiate new positions in Summit Industrial Income REIT, InterRent REIT, and Mainstreet Equity. These developments were not exclusive to small-cap REITs as our colleagues also recognized the chance to capitalize on these trends in their own portfolios, adding to their positions in NorthWest in the Burgundy Canadian Equity and Burgundy Partners’ Canadian Income Funds. Investor disdain for Canadian REITs presented opportunities across mandates, and our broadened exposure demonstrates how we can leverage ideas to the widest possible extent.

E-commerce

One of the first trends we analyzed was the accelerated adoption of e-commerce. Initially, it seemed to us that this could only have negative implications for real estate – lockdowns forced consumers out of physical stores almost overnight, leaving retail landlords in the lurch. We soon realized that while transactions were shifting online, the physical goods themselves still had to be stored somewhere. These goods were moving out of brick-and-mortar stores and into warehouses and fulfillment centers, both of which are a form of industrial real estate.

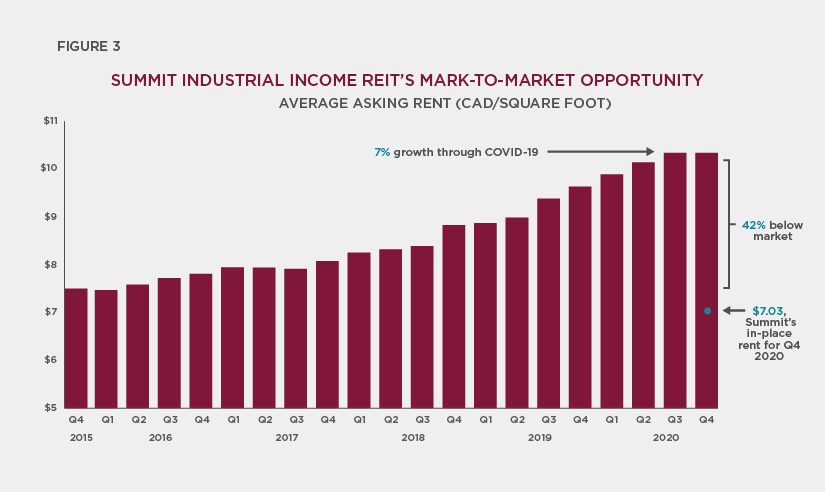

This shift was core to our thesis on Summit Industrial Income REIT, which leases warehouses in Ontario, Quebec, and Alberta. As e-commerce has grown to represent a larger part of retail sales, the resulting demand for the warehousing and distribution space has pushed rents up. Since 2015, average asking rents for industrial real estate in Canada have risen 36%, and this has been uninterrupted by COVID-19. Given that vacancy across Canada is low (and as low as 1% in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), which is Summit’s largest market), rental rate growth may continue after COVID-19. Increases in market rates do not instantly flow through Summit’s financials and create a “mark-to-market”1 opportunity upon lease renewal. The average tenant in Summit’s properties is paying rents 42% below market rent, meaning that there is a significant tailwind for Summit’s rental income as leases roll over. This spread exists because Summit’s average lease term is five and a half years, meaning many tenants are still paying market rental rates from 2015 and 2016. Recall that this was around the time that e-commerce penetration was growing and consequently driving demand for industrial real estate. This increased demand meant that market rental rates began appreciating at a faster rate than they had historically, creating a widening gap between market rents and Summit’s average in-place rent.2 Depicted in Figure 3, this mark-to-market lease renewal opportunity shows Summit’s average in-place rent per square foot compared to the Canadian average industrial rent on new leases:

Sources: Company filings, JLL Research

On the surface, the benefits of accelerated e-commerce adoption seem to accrue exclusively to online retailers and software companies, but Summit is an example of how overlooked opportunities exist beyond the clear winners. The share prices of immediate e-commerce beneficiaries quickly reflected our new retail reality, but many indirect beneficiaries and top-tier management teams’ efforts to adapt have been overlooked, creating opportunities for investors like Burgundy.

Immigration

After our work on industrial real estate, we shifted our focus towards residential real estate, and we spoke to management teams from across the country. While market dynamics differed by region, we found that these meetings almost universally involved a discussion on the importance of immigration in supporting rental markets. When the Government of Canada announced increased immigration targets in October 2020, we were reminded of these conversations, and we attempted to understand what this could mean for apartment demand.

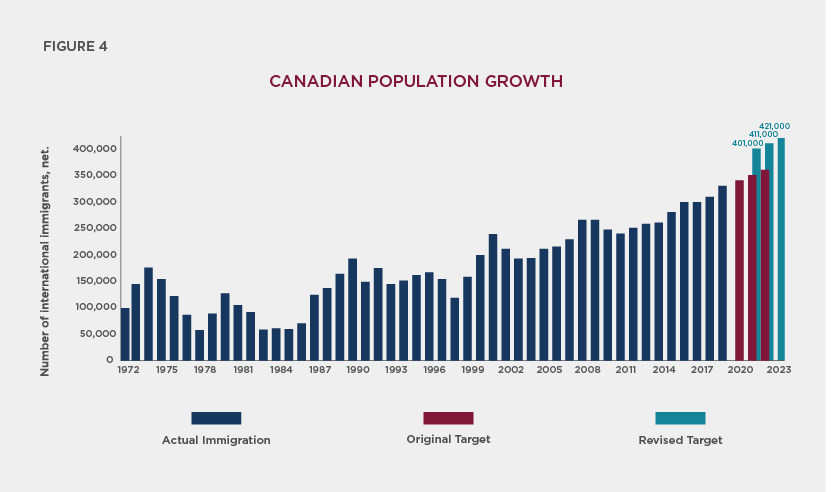

The Liberal government’s new plan aims to welcome over 400,000 new Canadians each year from 2021 to 2024. If successful, these numbers would represent the highest annual immigration numbers since 1911. We were able to find data back to 1972, which is charted in Figure 4, along with the original and revised COVID-19 immigration targets:

Sources: Company filings, JLL Research

Assuming an average household size of three and a 70% propensity to rent, this new plan could result in 100,000 rental units of annual demand growth, which will be in addition to any demand created by interprovincial migration. It is unlikely this increased demand will be met with sufficient supply. At present, there are 2.2 million rental apartments in Canada, with 30,000-40,000 units built per year. Supply growth has been challenged since the 1980s, as privately owned condo developments have overtaken purpose-built rentals. As of November 2020, condos make up 85% and 75% of units under construction in Toronto and Vancouver.

Stepping back, this means 100,000 new renters will be vying for only 30,000-40,000 units of new supply, creating a very tight rental market. Even before the pandemic, heightened immigration levels resulted in a vacancy rate in Canada’s apartment sector of only 2.2%, leading to annual rental rate inflation of 4% in 2019.3 We believe our two residential REITs, Mainstreet Equity and InterRent REIT, are well-positioned to benefit from this dynamic. Mainstreet Equity owns 13,500 apartments in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia. With average monthly rents of only C$986, the company focuses on affordability. Similarly, InterRent REIT owns 11,400 apartments across the GTA, Ottawa, Montreal, and Vancouver, focusing on slightly higher-end units with average rents of C$1,302. I will return to these two investments shortly when I discuss inflation and the institutionalization of real estate.

Lower Interest Rates

As outlined in the introduction, one of the earliest responses from central banks to the onset of COVID-19 was to aggressively cut rates. In the flurry of non-stop news coverage, it was easy to overlook how much of a boon this would be for REITs in the moment. Debt is a meaningful component of the capital structure of a REIT, making falling interest rates a tailwind. Since REITs use fixed-rate debt and stagger debt maturities, the benefit of lower rates is not instant, but our REITs are already taking advantage of this low-cost financing to both refinance existing debts and fund opportunistic acquisitions. For example, Summit raised C$200 million by issuing a five-year bond in December 2020 that carries a fixed interest rate of only 1.8%, which compares to the company’s weighted average interest rate of 3.7%.

This trend benefits residential real estate even more than other real estate sectors, as mortgages against residential properties are eligible for insurance with the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), a crown corporation. Given that the CMHC-insured debt is essentially backed by the Government of Canada, it qualifies for a very low rate. As a result, residential REITs like Mainstreet and InterRent are now able to finance asset purchases with 10-year fixed rates as low as 1.6%. Low rates may not persist indefinitely, but while interest rates are low, our REIT portfolio is slowly locking in higher future earnings. By funding acquisitions and refinancing using long-dated, inexpensive debt, we as investors are offered visibility in what may be an impermanent low-rate environment. This clarity, coupled with our comfort in their tenants’ resiliency, means we can have greater conviction in the ability of these holdings to produce stable, growing streams of cash flow in the future.

Falling interest rates have also created concerns around inflation as we emerge from the pandemic. Since rental rates tend to rise with inflation, real estate offers a hedge against this type of environment. However, some forms of real estate are better hedges than others – if market rents are rising with inflation, but tenants are on long-term leases, then the REIT cannot pass along those increases to tenants, and therefore provides no inflationary hedge. Asset classes in which there is naturally higher tenant turnover, like residential real estate, offer the best protection, making Mainstreet and InterRent well-positioned. Especially now, during a time of such strain, it is also important to consider the importance of affordability in residential real estate. We take comfort in the fact that both Mainstreet and InterRent offer units below the national average of C$1,7144 per month – as described above, Mainstreet’s average monthly rent is C$986, and InterRent’s is C$1,302.

Institutionalization of Real Estate

Despite driving our effort from the start, it was not until our team sat down in December to codify the learnings of our deep dive that we identified this final trend. The institutionalization of real estate refers to the shift in ownership of all types of real estate from small investors to institutions, like REITs or pension funds. Historically, real estate has been viewed as a bond proxy and was mainly owned by individuals or small groups – a group of doctors owns a medical office building, a private investor owns an apartment with a few suites, and so on. Traditionally, only trophy assets like downtown office buildings and malls like the Toronto Eaton Centre were owned by institutional players, leaving the rest of the market highly fragmented. However, as interest rates have declined, institutional investors have increasingly turned to real estate in search of higher yields.

As a result, managing institutional capital has become a new business for some REITs. Many institutional investors do not have the in-house real estate expertise that REITs have, so it is beneficial to form joint ventures, whereby the REIT earns fees for managing the institutional investor’s capital. This was core to the thesis on NorthWest Healthcare Properties REIT. In late 2019, NorthWest launched its third-party capital business by partnering with GIC, the Singaporean sovereign wealth fund, to manage C$3.4 billion of GIC’s capital. Our belief was that the market was not ascribing any value to the potential of the third-party capital business, which can be thought of as a miniature, healthcare-focused version of Brookfield Asset Management, and that this was a “free option.” COVID-19 has demonstrated how critical healthcare infrastructure is and the importance of having a well-capitalized owner of these assets. Through 2020, NorthWest launched two new joint ventures, one in continental Europe and one in the United Kingdom, increasing committed third-party capital to C$8.5 billion.

A longer-term effect of this shift in ownership is that real estate can offer growth through redevelopment, not just yield. This means that, with some renovations, there is the opportunity to raise rents. The runway for redevelopment is long, especially in residential real estate, where ownership remains extremely fragmented – the 10 largest industry participants own just 12% of the 2.2 million apartment suites across Canada. To illustrate why this opportunity exists, consider the example of an individual investor who owns a small low-rise residential building. This investor’s investment objective is to have a stable source of passive income, and, therefore, keeping occupancy high is a top priority. Having a tenant move out, only to invest tens of thousands of dollars in renovating the suite and forgo months of rent is not aligned with this investor’s priorities. As a result, when this property is sold, the in-place rents can be significantly below market levels and renovations are often needed.

Redevelopment potential underpinned our theses in both Mainstreet Equity and InterRent. Both companies seek to acquire multi-unit residential properties from small, capital-constrained owners, often below replacement cost, and renovate them. These management teams are experts in redevelopment: Mainstreet operates its own direct supply chain in China to achieve bulk discounts on renovation materials like flooring, and InterRent’s management team has been redeveloping apartments together for 30 years. Once the property is renovated, InterRent and Mainstreet can increase rents above those in place at acquisition, leading to significantly higher operating income from the property. This has proven successful for InterRent over the past decade, with funds from operations (FFO)5 per share compounding at 18% per year since 2011.

Since Mainstreet is structured as a typical publicly traded entity and not a REIT, it differs slightly from the other REITs discussed in this piece. This is important to understand in the context of the redevelopment program, as it has allowed Mainstreet to augment per-share earnings growth by repurchasing shares opportunistically when they trade below net asset value (NAV).6 REITs are known to rely heavily on equity issuances as a source of funding, but in its life as a public company, Mainstreet has never issued shares, and the total shares outstanding have in fact decreased by 10% since 2011. These capital allocation decisions, coupled with Mainstreet’s redevelopment program, have resulted in FFO compounding by 19% annually over the past decade.

Final Thoughts

I will admit that when I began my research on this sector, I had unnuanced expectations of what I would find. I thought REIT investing was prescriptive and singularly focused on finding the most under-appreciated assets, but exploring this industry during such a volatile period revealed accelerated trends and burgeoning opportunities.

Rarely has an industry sold off as indiscriminately as Canadian real estate did in 2020, with the S&P/TSX Capped REIT Index delivering its worst relative performance in relation to the S&P/TSX Composite Index in 23 years.7 Immediate concerns around empty offices and malls were extended to the entire sector, with the market believing it was impossible for some REITs to actually benefit from the pandemic. As these concerns continue to weigh on the entire REIT sector, we believe the companies that are benefitting from trends in e-commerce, immigration, low interest rates, and the institutionalization of real estate offer very good value. While our focus on the REIT space has increased in the past year, the research we have applied to this sector has not been a departure from our typical process. Our experience getting to know the REIT industry has reinforced the importance of reading extensively on businesses, learning from management, and using a little common sense. When we apply these strategies, we can find good investments, even when the circuits are breaking.

1. An accounting method used to assess the true value of assets and liabilities based on current market conditions.

2. The weighted average of rents being paid by current tenants of a property. Differs from market rent in that it is based on lease agreements between landlords and tenants, not market conditions.

3. CMHC Rental Market Report, 2019.

4. February 2021 national average rent as per Rentals.ca.

5. A measure of cash flow generated by a REIT, calculated by adding depreciation, amortization, and gains on sales of property back to net income.

6. By not being structured as a REIT, Mainstreet does not have to distribute its earnings as dividends.

7. The S&P/TSX Composite is the headline index and the principal broad market measure for the Canadian equity market. It includes common stocks and income trust units.

Sources: Company filings, JLL Research; Canadian Conference Board, Government of Canada; Consultation, CBRE

This communication is presented for illustrative and discussion purposes only, and is not intended as an offer to invest in any investment strategy presented by Burgundy. It is not intended to provide investment advice and does not consider unique objectives, constraints or financial needs. Under no circumstances does this communication suggest that you should time the market in any way or make investment decisions based on the content. Select securities may be used as examples to illustrate Burgundy’s investment philosophy. Burgundy portfolios may or may not hold such securities for the whole demonstrated period. Investors are advised that their investments are not guaranteed, their values change frequently and past performance may not be repeated. The information contained in this communication is the opinion of Burgundy Asset Management and/or its employees as of the date of posting and are subject to change without notice. Investing in foreign markets may involve certain risks relating to interest rates, currency exchange rates, and economic and political conditions. From time to time, markets may experience high volatility or irregularities, resulting in returns that differ from historical events. Please refer to the Legal section of Burgundy’s website for additional information.

Please note that the information provided herein is not necessarily a balanced demonstration. As a result, the data relayed here is not necessarily reflective of the corresponding data for the entire strategy in question. Furthermore, the holdings described here do not represent all securities purchased, sold, or recommended for advisory clients. Please note that the information included herein does not entail profitability, and that this presentation does not provide the average weight of the holdings during the measurement period nor the contribution these holdings made to a representative account’s return. Because Burgundy’s portfolios make concentrated investments in a limited number of companies, a change in one security’s value may have a more significant effect on the portfolio’s value. A full list of securities is available upon request.