As he sifts through the noise of a 24-hour news cycle, Investment Analyst Donald Gawel offers insight into the world of value investing and valuation. Using case studies as evidence, Donald disrupts the myths surrounding growth and value stocks, offers his tips for avoiding traps, and advocates for a balanced approach when assessing what a business is worth.

One of my guilty pleasures in life is watching investors, strategists, and reporters debate various themes in the stock market. These short clips are an integral part of my morning news routine, some added levity alongside breaking articles and morning emails. I generally find these debates act as a good barometer of market sentiment at any given time, helping me determine what Mr. Market might be feeling. While these debates do absolutely nothing to change my thinking or planned work for the day, they do have some great entertainment value.

Lately, I have seen two topics getting a lot of airtime. The first is one that eminent investor and writer Howard Marks discusses at length in his latest memo, “Something of Value”1: the great debate between owning “growth vs. value.” When this unfolds on the air, one talking head might say something about “expecting value to outperform for the next six months,” and another commentator might cut in with an argument about how “a divided congress is better for growth stocks over value.” The second topic receiving airtime today is whether valuation is an investment tool altogether. Some in this debate have argued that if a company is a disruptor, or a concept stock, financial metrics do not matter because there is nothing to use as the basis of valuation – valuation simply cannot be done. Alternatively, if the company has a large total addressable market (TAM), a high growth rate, a path to higher margins, and a competitive advantage, there is no valuation that is too high to stop you from buying those attractive business qualities.

The concepts of “value” and “growth” are often simplified as follows: Value stocks have low price-to-book or price-to-earnings ratios or trade below net asset value. Growth stocks grow well in excess of the general market and have a long runway of this outsized growth ahead of them (even if those businesses look expensive on traditional value metrics). I would argue that the overall debate in owning growth versus value at any particular moment is largely an exercise of blowing hot air. More importantly, it does not (and should not) have much of an impact on our investment philosophy. As bottom-up investors, picking between growth and value does not make a lot of sense.

First of all, why would you pick only one category? No one is forcing you to pick. Why would you play a game with one arm tied behind your back? Why not buy the best businesses, regardless of their classification, for less than their true worth? Secondly, the distinction between growth and value is just a fuzzy, made-up concept to begin with. We agree with Warren Buffett when he stated that growth and value are “joined at the hip,” but there is a pervasive notion in the marketplace that these investment philosophies are opposites. This distinction does not make a lot of sense when your investment philosophy is based on business fundamentals and intrinsic valuation. Let me explain why.

Would You Free Climb K2?

The investment process is a bit like trying to climb a sheer rock face. It is in the best interest of the rock climber to establish anchor points along the way for safety. After these anchors are hammered into the rock face and secured, the climber clips in, advancing the climb past this point and establishing new anchor points higher up. These anchor points take time and effort to establish, but they are something to fall back on. When investing, these anchor points are what we deem a company’s intrinsic value. We feel safe investing when the share price is below this intrinsic value “anchor,” and feel even better when we expect that anchor to get higher in the future. For example, think of a company successfully introducing a new product or business line and increasing its intrinsic value. This is akin to the climber who continues to venture upwards, past the previous anchor point, to establish a new higher one. We now have a strengthened position for the climber to launch the next ascent.

Now, completely ignoring valuation in the investment process is similar to climbing the rock face with no safety harness, no rope, no carabiners, and no anchor points. Sure, the free solo climbers can ascend quickly and there is nothing limiting how far or fast they can climb, but if they slip, they can fall very far, very fast. Without a sound valuation to anchor onto, you may quite easily plummet to your death. In the investing world, this would mean a permanent impairment of capital. At its best, the philosophy that valuation does not matter over the long term is simply reckless. At its worst, it could be fatal.

So, Why Does Valuation Matter?

At Burgundy, we classify ourselves as quality-value investors who focus on bottom-up business analysis and fundamental value. In other words, we want to purchase financially productive businesses at a discount to their intrinsic value. Valuation serves as a tool in our analytical framework. Investors need to have a framework to determine the potential future earnings power of a business to protect themselves from irrational investments and markets. If a company is trading at a higher price than even the most rose-coloured, optimistic business forecast would imply, more likely than not, that is a recipe for disaster. While we agree that business quality matters more than valuation and that the pace of disruption is faster today than ever before, valuation still matters.

The pure math component to arrive at the intrinsic value of a business is pretty simple. An investor forecasts out the future cash flows of a business and discounts those cash flows back to today to arrive at the net present value, or intrinsic value, of the business. Now, getting to that forecast requires a tremendous amount of work, including evaluating business quality, substantiating competitive advantages, gaining confidence in management, and understanding reinvestment opportunities. At the end of the day, though, we use expected future cash flows to help us think about business value. It then makes sense that the growth rate of those cash flows (positive or negative) impacts the intrinsic value. Growth is therefore an input to the intrinsic value of a business, and we want to buy the business at a discount to its intrinsic value.

It does not make sense to buy a business simply because it is a “cheap” stock, the same way it does not make sense to buy a business simply because it is growing “quickly.” These characteristics have absolutely nothing to do with what the business is actually worth from an intrinsic standpoint. Our view is that valuation matters. If a company passes our business quality screen, finds itself on the Dream Team2, and is trading at a fair discount to its intrinsic value, that would indicate it is time to buy the business.

How Do We Think about Value?

Investors need to realize that some value companies are overvalued, even though they are statistically “cheap,” because their competitive position is deteriorating at a much faster rate than people realize. In other words, their intrinsic value is declining over time. These companies are commonly known as value traps or melting ice cubes. It is equally important to realize that some growth companies are overvalued because the underlying assumptions regarding that growth, future profitability, or reinvestment opportunities are simply too aggressive and do not leave an adequate margin of safety or any room for error. These are known as growth traps, and for good reason (recall the risk of the free solo climber we discussed earlier).

Beyond the “knowable” forecastable period of a business (usually between five and 10 years), investors must make an assumption on the terminal value or the remaining life of that business. Overestimating the terminal value of a business exposes investors to terminal value risk, but predicting into the future is no easy feat. Investors must face the challenging reality that a significant portion of a company’s value exists beyond the forecastable future. And as we can see from 2020, sometimes no amount of financial modelling can predict what a year will bring.

Burgundy takes a conservative approach to these terminal assumptions. We typically use an 8-10% discount rate and a terminal growth rate of around 2% and have done so consistently throughout numerous business cycles. We apply this discount rate because it tends to reflect the average long-term returns of the market, and we seek to invest in companies that we think will generate returns in excess of the market. The terminal growth rate we use roughly reflects a zero-real-growth scenario. We do not change these assumptions based on market conditions. The future will always be uncertain, but we believe applying a conservative discount rate and terminal value provides us with some protection.

I am an advocate for using case studies and learning from real market examples. You can see a lot further when you stand on the shoulders of giants. The examples below illustrate how these traps may reveal themselves and what we can learn from them.

Case Study #1: The Value Trap

Perhaps the most famous value trap of all is Berkshire Hathaway. Not the financial conglomerate and investing juggernaut it became, but the small capital-intensive New England textile mill it once was.

Warren Buffett has called Berkshire the “dumbest stock” he has ever bought. He went into Berkshire because it was statistically cheap and selling well below its working capital. The business made sense to him through the lens of his “cigar butt” approach to investing. In Buffett’s words: “A cigar butt found on the street that has only one puff left in it may not offer much of a smoke, but the ‘bargain purchase’ will make that puff all profit.”3 That one good puff from Berkshire, along with its cheap price, made up for it being a pathetic company.

Berkshire was in the low-end North American manufactured textile business, which was suffering from secular decline, immense competitive pressures and a declining topline. In addition, the commodity products sold by Berkshire had no real brand or moat and the only source of differentiation was price. Historically, Berkshire had been actively closing down textile mills, liquidating them, and buying back stock with the goal of increasing the intrinsic value per share on the remaining business and subsequent shares. Simultaneously, new textile technologies were coming to market, further increasing the pricing pressures and competition in the industry and driving down incremental returns. Just to maintain its economic position meant Berkshire would have to spend significant amounts of capital. It was a capital-intensive business whose returns on invested capital were in continual decline. As Charlie Munger put it, “Nothing was going to stick to our ribs as owners.” Berkshire is a great example of a value trap that experienced significant technological disruption. This cranked up the competitive heat and led to the ice-cube business model melting faster than even Buffett realized was possible.

Like most things in life, value traps are obvious to spot with the benefit of hindsight. The important thing for investors to remember is that if a business does not display any competitive advantages and is not financially productive with its capital, it will be very difficult to grow its intrinsic value over time. The mistake investors make with value traps is they believe that a statistically cheap valuation translates into a wide margin of safety. This is not the case. No matter how “cheap” a business may be trading from a valuation perspective, you cannot ignore the underlying business quality. By ignoring quality and focusing on valuation, you will fail to recognize how fast the competitive landscape may be shifting below your feet, and you could be left owning an asset with a declining intrinsic value (aka, a trap).

We all know Berkshire later became the wildly successful investment conglomerate it is today. This was likely only possible because the business had Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger, perhaps the two best capital allocators in history, at the helm, investing outside of the declining core business. Berkshire was statistically cheap when Buffett bought it, but given the competitive pressures and declining fundamentals, it was still overvalued over the long term. As Buffett has said, “time is the enemy of the poor business.”

Case Study #2: The Growth Trap

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, during the height of the last tech bubble, Cisco Systems was a pioneer in providing end-to-end networking solutions to unify the information infrastructure of computer networks. Cisco was revolutionary at the time, creating an environment where all computers on a network could talk to each other regardless of location or computing language. Cisco provided solutions to the internet economy of the future and enabled businesses to leverage these powerful resources. The company was on the cutting edge of a marketplace with an enormous TAM, and that got investors excited. Cisco benefitted from being the first mover, which led the company to command a dominant market share. In 1999, Cisco sold more than 80% of the routers that corporations use to send data communications over the company’s networks.

Cisco benefitted from economies of scale, which led to industry-leading margins and high returns on invested capital. Cisco also benefitted from having a relatively captive customer base with a high degree of switching costs. At the time, Cisco routers would not talk to routers of other competitors on the same network system. Therefore, existing Cisco customers would continue to purchase Cisco routers exclusively. Otherwise, these customers would have to replace their entire network, a large and expensive undertaking that would not be worth whatever menial savings could be achieved by switching to a low-cost competitor.

These competitive advantages, combined with the unfathomable TAM of the internet, had investors very excited. In the 2000 shareholder letter, Cisco’s Chief Executive Officer wrote about the future of this environment, “Over the next two decades, the Internet economy will bring about more dramatic changes in the way we work, live, play, and learn than we witnessed during the last 200 years of the Industrial Revolution.” Looking back, they were absolutely right, and investors clamoured to be a part of the new technology frontier. Internet-related stocks, both real businesses like Cisco or famous “dot-coms” that were not really businesses at all, inflated to all-time highs.

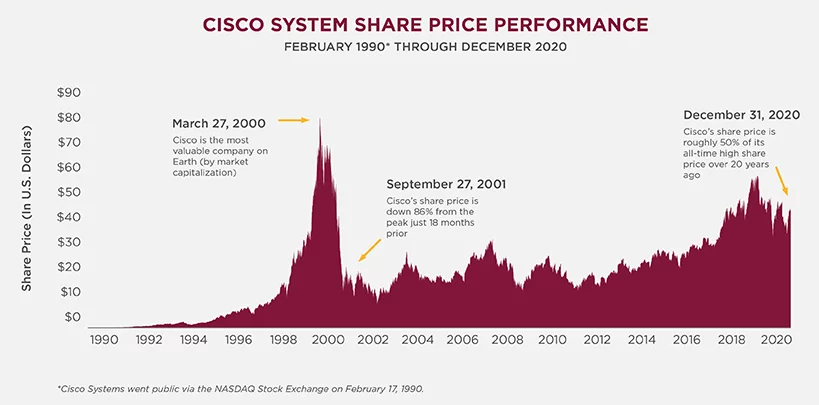

What is more, Cisco had a strong business model and financial performance to back up its ever-inflating share price. Setting aside the frenzy of the internet bubble, it is easy to understand why investors were so excited about Cisco at the time. In the period from 1989 through 1999, Cisco compounded revenue at an annual growth rate of over 83% and compounded adjusted earnings at a rate of over 85%. Cisco’s incredible financial performance led to an annualized share price return of over 98% from its initial public offering (IPO) in 1990 through to its highs in March of 2000. In fact, in March of 2000, not one of the 37 research analysts covering Cisco had anything lower than a “buy” or “strong-buy” rating on the stock. All the while, Cisco had a price-to-adjusted-earnings multiple of approximately 130 times forward earnings. On March 27, 2000, Cisco became the most valuable company on Earth (as measured by market capitalization) with an equity value of $569 billion. Then the tech bubble burst and from the period of March 27, 2000, through to September 27, 2001, Cisco’s shares were down 86%.

Adjusted for share splits, in the 20-plus years after the tech bubble, the Cisco share price has only ever got back to approximately 70% of its tech-bubble high. It is currently trading at roughly 50% of its all-time-high share price, at a forward price to adjusted earnings multiple of approximately 11.5 times (compared to approximately 130 times at the peak).

So, what happened? How did so many people get it so wrong on Cisco’s stock? We know the internet went on to revolutionize the world, spurring innovation and creating business models few could dream of at the time. So, it was not that the internet economy never took off. Did Cisco suddenly become a terrible business? Well, from 2000 to 2020, Cisco grew revenue at a compounded annual rate of close to 5% and adjusted earnings per share at a rate of approximately 8.8% annually for 20 years. This is an impressive long-term track record for any business. So, the question remains: What happened?

The answer lies in the growth expectations that investors placed on the business and the valuation in which they were willing to pay for that growth. Howard Marks famously said that, “being too far ahead of your time is indistinguishable from being wrong.” This outlines Cisco’s journey quite well. It sounds basic, but current stock prices are reflective of future expectations. In the case of Cisco, the expectations investors placed on the growth of the business were simply too large and too early in the evolution of the internet and its capabilities. If we take a bottom-up view of Cisco’s business, we can see that they were benefitting from artificially high levels of sales into venture-backed companies. When the companies eventually went bankrupt and were liquidated, these would flood the market with cheap, second-hand Cisco products. Additionally, lucrative markets attract competition. Cisco took its foot off the gas pedal and opened the door for competitors to innovate and bring a superior product to market, which opened the door just enough for these competitors to start chipping away at Cisco’s market share. Finally, networking product sales are not recurring. Once customers make a purchase, they will not need to make additional purchases until they grow their operations or the technology depreciates. As a result, Cisco started going after larger communications infrastructure customers, where the company’s competitive advantages did not carry over and the competition was fiercer.

When the euphoria ended and the fundamentals started to show weakness, investors became much less willing to pay such a high multiple on these aggressive growth estimates, and the share price collapsed. Ultimately, the valuation mattered.

Invest Along the Spectrum

While the “growth vs. value” debate may be provocative on a 24-hour news cycle, where riled-up personalities are pitted against each other and fueling the gamification of the stock market, it is an oversimplified version of a more nuanced conversation. At Burgundy, we prefer to invest in businesses across the growth-value spectrum. If we have conviction that the growth is sustainable, forecastable, and underrepresented in the price, we are more than willing to pay for growth. Alternatively, we are just as happy to own value stocks if we believe that the business fundamentals are strong and the company has true competitive advantages that are being overlooked by the market. It does not matter if the companies are perceived as traditional value, or growth, or anywhere in between. Both growth stocks and value stocks have terminal value risk. When it comes to growth stocks, trees do not grow to the sky. For value stocks, the last 10 years of a company’s history may not look like the next 10 years. Growing cash flows can be your margin of safety, just as much as stable cash flows.

This approach requires a commitment to balance and an open mind. We will not ignore business quality for the sake of an attractive valuation, and we will not ignore the valuation because we see attractive quality or growth characteristics. We weigh all these risks at once and believe that this strategy helps us to avoid potential value or growth traps. We do, however, adhere to a quality bias at Burgundy. We want to own the best businesses in the world, and we would much rather pay a fair price for a phenomenal business than a great price for a bad business.

There is No Summit

At Burgundy, we are long-term investors, and when you are able to look at the world through a long-term lens, it brings a much-needed perspective. By thinking about our investments over an extended time horizon, we can ignore the latest noise spewed by the talking heads on TV and focus on the best predictors of long-term success, business quality, and competitive advantages. Ultimately, we strive to buoy investment results for our clients by purchasing at a reasonable price, sticking to quality companies we strongly believe will outperform the broader market over time, and reaping the rewards of compounded earnings.

Buffett’s experience with Berkshire has taught us to avoid cigar butt businesses, and these would never find themselves on the Burgundy Dream Team, list. What we saw during the tech bubble with Cisco has shown us that estimations of worth are important regardless of how high quality a business model is or how fast that business is growing.

The point is that valuation matters, especially over the long run. When securities are priced to perfection, or incorporate overly aggressive estimates into the share price, investors must practice caution and discipline. The safety harness is not just another item in a climber’s accoutrement; it is a life-saving anchor. Intrinsic value should not be understated either. It is more than just a tool in an investor’s kit. Prudent use of these anchor points helps us along the way as we look to buy high-quality businesses when they go on sale. In the world of investing, it is not a race to the top of the mountain because the reality is that there is no summit. It is an arduous and continuous ascent that we think necessitates anchor points of intrinsic value. In the end, the aim is to challenge ourselves to keep climbing.

1. Marks, Howard (2021) “Something of Value.”

2. A Dream Team company embodies the business, financial, and management characteristics that Burgundy deems high quality, but its current market price does not offer enough of a margin of safety to warrant investing at this time. Burgundy monitors these companies, waiting for the right purchase price.

This communication is presented for illustrative and discussion purposes only, and is not intended as an offer to invest in any investment strategy presented by Burgundy. It is not intended to provide investment advice and does not consider unique objectives, constraints or financial needs. Under no circumstances does this communication suggest that you should time the market in any way or make investment decisions based on the content. Select securities may be used as examples to illustrate Burgundy’s investment philosophy. Burgundy portfolios may or may not hold such securities for the whole demonstrated period. Investors are advised that their investments are not guaranteed, their values change frequently and past performance may not be repeated. The information contained in this communication is the opinion of Burgundy Asset Management and/or its employees as of the date of posting and are subject to change without notice. Investing in foreign markets may involve certain risks relating to interest rates, currency exchange rates, and economic and political conditions. From time to time, markets may experience high volatility or irregularities, resulting in returns that differ from historical events. Please refer to the Legal section of Burgundy’s website for additional information.

Third-party materials that are referenced or linked here are not necessarily endorsed by Burgundy and are entirely independent of Burgundy. Burgundy is not responsible for third-party content linked here or any consequences of engaging with third-party content. Any third-party materials referenced or linked here are provided for informational and contextual purposes only.