“It’s 6:30 in the morning and I’m checking my inbox for the first time. It’s early. It’s also earnings season, when most public companies are releasing their quarterly earnings and market participants are on edge. At the top of my inbox is a news release from a company I recommended to my portfolio manager. I open it and start reading. It’s the company’s third-quarter earnings release. I skim the report, locate the table of key financials, and begin studying the figures. Something is wrong.

The results are abysmal. Sales are down and profits have evaporated. I dig into the text in the press release. Apparently there were operational issues at the company’s main manufacturing plant–high staff turnover and difficultly procuring raw materials–which held back production and pushed up costs. This is going to be ugly, I think to myself.

Three hours later, the Toronto Stock Exchange opens. The company’s stock begins trading down 30%. My stomach churns. How could I have made such a big mistake? Everything I read told me this was a good company. I researched it for months and never read anything about these operational risks. My phone rings. It’s my portfolio manager and he’s calling to ask what happened. I cringe and pick up the phone.”

Seasoned analysts will probably recognize this story. Newcomers to the investment business usually experience something like this in their first few years on the job: An investment recommendation does badly because of an unexpected problem. The problem is unexpected because it was never discussed in filings, research reports, or in meetings with the management team. This unfortunate occurrence underscores two challenges facing investors.

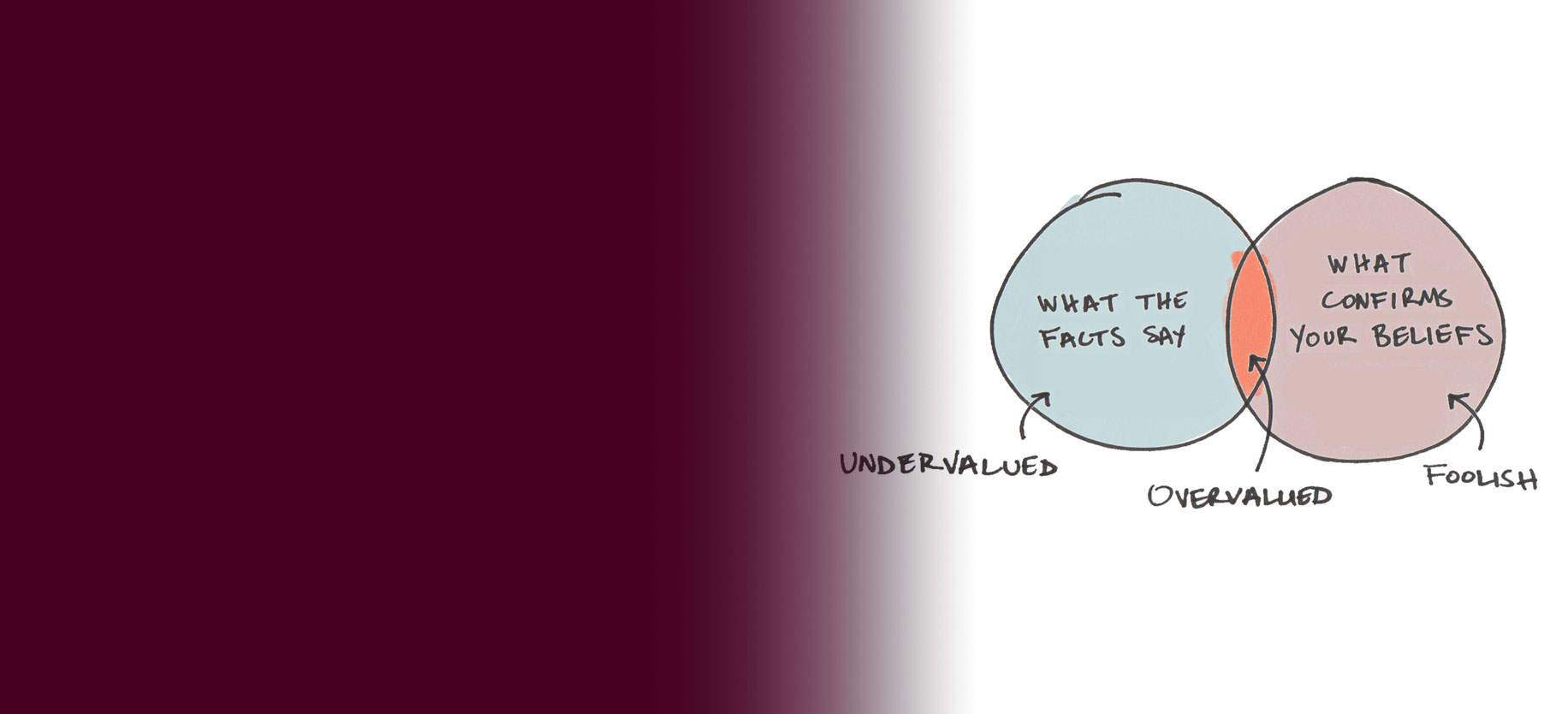

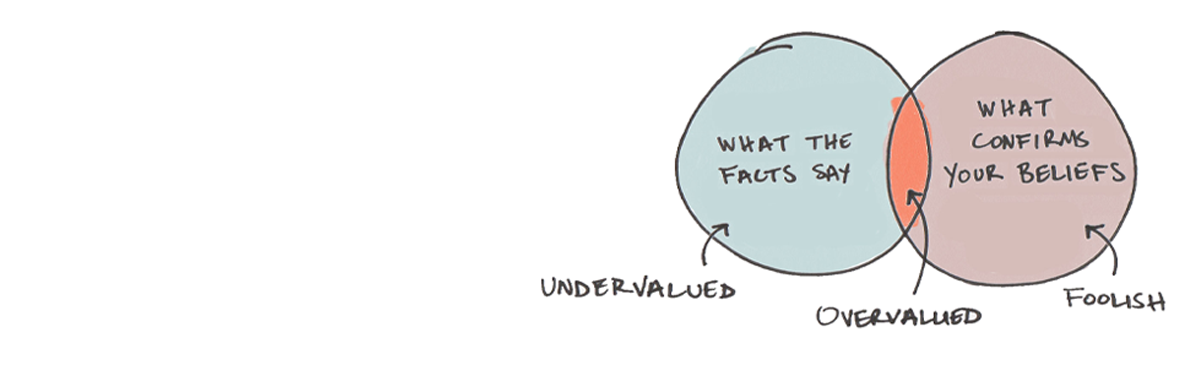

The first challenge comes from the inside. Investors suffer from personal behavioural biases. A particularly deadly bias is confirmation bias, which leads investors to search for confirming evidence and ignore disconfirming evidence. The more time an investor spends researching a company, the stronger the search for confirming evidence becomes.

The second challenge comes from the outside. The capital market is engineered to get investors to buy. Companies want capital; management teams want a higher stock price for their stock options; brokers want trading revenue; and investment bankers want issuance fees. As a result, everything that the capital market distributes to investors–annual reports, investor presentations, research reports, and so on–paints an optimistic picture. In short, the capital market delivers the confirming evidence that the investor’s confirmation bias craves. While securities laws require some risk discussion, these disclosures are often superficial. The real risks of an investment are usually hidden, requiring investors to hunt for the disconfirming evidence that allows for a balanced view of risk.

Among investors, there are a variety of ways to approach this challenge. I like to complete a checklist before investing in a new company. Referring to a list helps me to uncover hidden risks by forcing me to systematically look for disconfirming evidence. While this checklist certainly does not guarantee investment success, it does help to counterbalance the optimistic view crafted by the capital market.

Below is a sample of items from my checklist. My actual checklist is longer (and involves more tedious steps), but I hope this sample gives you a sense for how my checklist serves to widen my perspective on investment risk.

1) Gauge management’s integrity, incentives, and alignment:

- Check management’s personal trading history. Several times I have been told a rosy story by a CEO, only to find he or she is selling the company’s stock.

- Speak to someone who knows the management team. Sometimes I can find ex-employees or others in the business community who can opine on the integrity of management. Bankers and brokers will even occasionally tell me when they think a management team is too aggressive in their promises to the investment community.

- Read the management compensation section of the proxy circular. Management teams often pay lip service to returns on invested capital, but only a fraction have their compensation linked to this metric. I am often disappointed when I read this section of the circular, finding incentives linked to absolute dollars of revenue growth or, even worse, adjusted profits where the management team picks the adjustments.

2) Study the financial and operating history of the company, paying particular attention to:

- Goodwill impairments and restructuring charges, which may point to poor capital allocation decisions.

- A low conversion rate of earnings into cash flow, which may signal aggressive accounting.

- Swings in revenues and margins, which offer clues into the cyclicality and cost structure of the business.

- 2007 to 2009, which shows the performance of the business in a difficult economy. For this step, I read the annual reports from 2007 to 2009 to put myself in the shoes of an investor living with the company through the financial crisis.

3) Analyze the competitors and peers:

- Search for examples of blow ups. I sometimes find companies in similar markets (usually in the U.S., the U.K., or Australia) that have comparable business models to the company I am studying in Canada. If I can find a comparable company that has blown up, it usually serves as a great case study for what can go wrong.

- Look for direct competitors with better margins. If I can find a competitor who has better profit margins, that competitor must have more pricing power, greater scale, or be run more efficiently. In any case, it probably means the company I am researching is not the best company in the industry.

4) Build a flexible financial model and use it to:

- Stress test the business. Take an educated guess at the division of variable and fixed costs in the business, using the footnotes to the financial statements and any commentary from the management team. Apply a revenue decline informed by the performance of the business through past cycles and measure the percentage decline in earnings in the “stress case.”

- Infer what the market is pricing in. Take the current share price and use the model to deduce what assumptions the market is making about revenue and profit growth. This backwards modelling helps us to avoid bubble stocks where investor optimism is running too high.

5) Ask a teammate to play devil’s advocate:

- I ask a member of my team to take a fresh look at the company and try to blow it up. This person does not know the file as well as the other members of the team and is therefore less prone to confirmation bias. In short, he or she is less personally invested in the company. I am always surprised by how consistently the devil’s advocate exposes new investment risks.

While there are no hard-and-fast rules for expecting the unexpected, there are ways to better predict investment pitfalls. This checklist serves as a reminder to remain measured in times when I am pulled towards optimism over skepticism.

Image credit: 5 Common Mental Errors That Sway You From Making Good Decisions by James Clear

This post is presented for illustrative and discussion purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment advice and does not consider unique objectives, constraints or financial needs. Under no circumstances does this post suggest that you should time the market in any way or make investment decisions based on the content. Select securities may be used as examples to illustrate Burgundy’s investment philosophy. Burgundy funds or portfolios may or may not hold such securities for the whole demonstrated period. Investors are advised that their investments are not guaranteed, their values change frequently and past performance may not be repeated. This post is not intended as an offer to invest in any investment strategy presented by Burgundy. The information contained in this post is the opinion of Burgundy Asset Management and/or its employees as of the date of the post and is subject to change without notice. Please refer to the Legal section of this website for additional information.