3 for 30

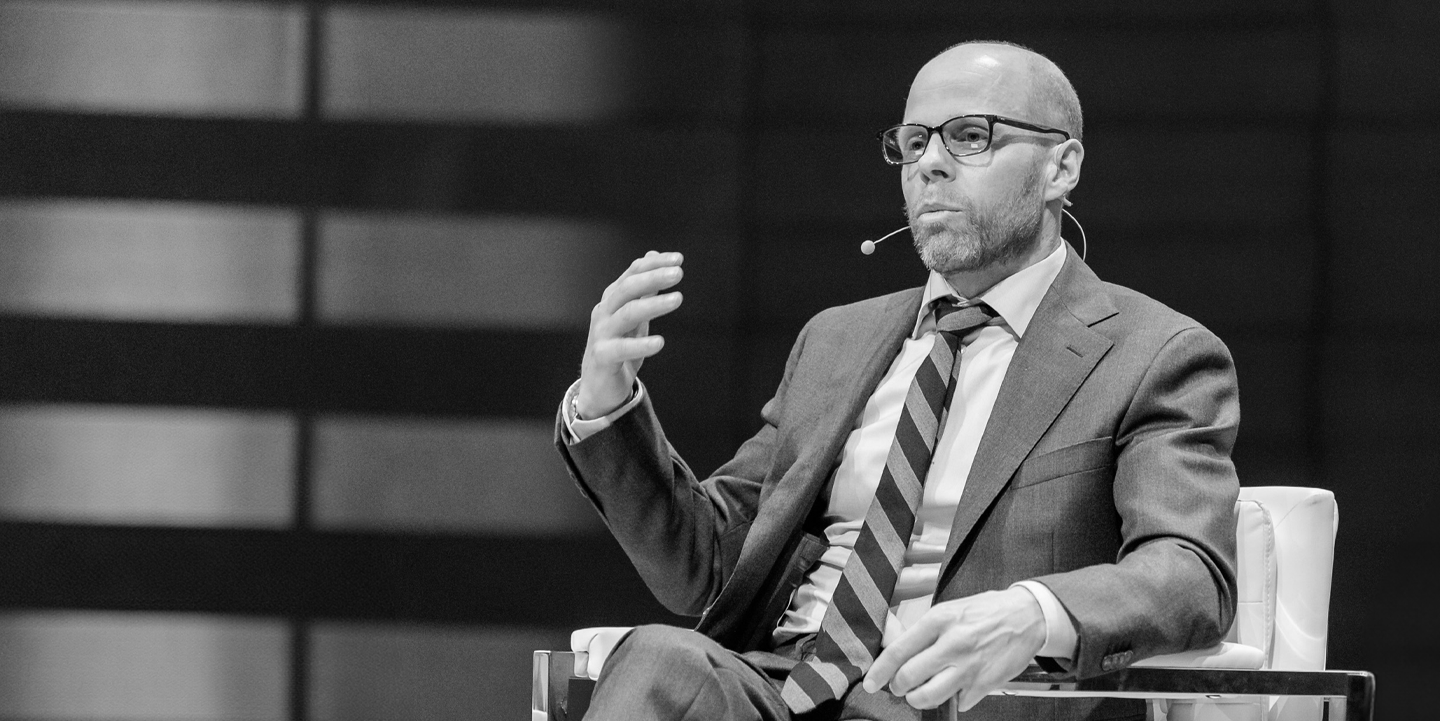

Can you distill a three-decade career down to three essential lessons? On the heels of his 30th anniversary, Portfolio Manager David Vanderwood is up to the challenge.

In this View from Burgundy, David reflects on the guiding principles that have shaped his career, offering insight into navigating change, unlocking the magic of compounding, and embracing the power of patience.

KEY POINTS:

- Benefitting from the magic of compounding requires a commitment to patience.

- Changes and surprises are guaranteed, but human nature stays the same.

- Most fortunes are accumulated over many years.

- When moments of volatility and fear strike, it helps to be disciplined.

In 1994, I was in my early twenties, two years into my budding investment career, and working for a larger-than-life investor named Richard (Dick) Bonnycastle, who hired me to look after a portion of his family fortune that was earmarked for “safer” investments. Twenty years prior, Mr. Bonnycastle had made a great deal of money selling his family business, the highly successful romance book publisher Harlequin Enterprises. While I handled the lower-risk portion, Mr. Bonnycastle continued to focus on his twin business passions: venture investing and trading.

Mr. Bonnycastle and I could not have been more different. He was 60 years old, tall, actively single, experienced, and rich, with an air of aristocracy about him (one of his many homes was near Ascot in Britain, the prestigious horse racing venue). I was straight out of university, already engaged to be married, inexperienced, and broke, with $25,000 in student loans and still living in the modest family home of my upbringing in Ladner, B.C., a small farming and fishing village on the banks of the Fraser River. Mr. Bonnycastle recognized our differences and attempted to educate me. Upon hiring me, he transmitted two messages loud and clear. The first piece of advice: “David, the first $40 million is the toughest.” The second: “I don’t care what you do. You can go to the f&#*n beach. Just don’t lose money.” In Mr. Bonnycastle’s gruff and direct manner, he was trying to teach this neophyte investor about compounding.

February 2, 2024 marked my 30th anniversary as an investment manager. As I reflect on the past three decades, Mr. Bonnycastle’s sage advice, which I will return to shortly, has resurfaced, along with many other learnings. In this View from Burgundy, I will share the three most impactful lessons learned from 30 years of investment survival.

Lesson 1: Compounding is Magical

The power of compounding, or exponential growth, is pervasive in our world, from the spread of viruses to the accumulation of wealth. And yet, it is not intuitive to people. As Morgan Housel, author of The Psychology of Money and Same as Ever, has pointed out, we are wired to think linearly. Housel notes that figuring out the answer to 8 + 8 + 8 + 8 is not too challenging. If we are asked to solve for 8 x 8 x 8 x 8, however, most of us will reach for our calculator. Our lack of intuitiveness makes appreciating, and benefitting from, compounding a challenge. As Physicist Albert Bartlett once said, “The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function.”1 Given its elusive nature, compounding can feel supernatural, even magical.

The benefits of compounding make it a worthwhile challenge to overcome. Consider Warren Buffett’s roughly US$120 billion fortune. Ninety-nine percent of this 93-year-old’s wealth has accumulated since he was 50. Let me repeat that: 99% of Buffett’s vast net worth has piled up since he was 50. To break this down further, 11.5% compounded annually for 43 years will turn a little over US$100 million (Buffett’s estimated wealth at 50) into US$120 billion. That is supernatural.

Though incomprehensible to my young, broke self, this is the lesson Mr. Bonnycastle was driving at when he told me that “The first $40 million is the toughest.” And, as Buffett’s incredible compounding illustrates, Mr. Bonnycastle was right. Once a nice chunk of wealth is accumulated, even a small regular investment gain will turn it into a much larger chunk with the passage of enough time.

Mr. Bonnycastle’s other piece of advice, “don’t lose money,” is precisely what Buffett calls his investment rule #1 (his rule #2 is don’t forget rule #1). I expanded on this idea in my 2004 View from Burgundy, “The Eighth Wonder,” when I wrote that “negative numbers wreak havoc on compounding equations.” They sure do. If you lose 50%, you have to make 100% (a double) just to get back to where you started. That’s a tough ask, and it is why capital preservation is critical to enjoying the magic of compounding.

Once we understand the principles, the next question is: How can we benefit from compounding? One answer, once a little capital is saved, is ownership, especially ownership of good businesses that remain good businesses.

While determining which businesses will remain good is difficult, determining which are good today is easier. Let’s start with the observation that most good businesses earn a superior return on the investment entrusted to them by their shareholders. A good proxy for this is return on equity (ROE), the annual net earnings (or profit) after-tax, divided by the capital shareholders have invested in the business.

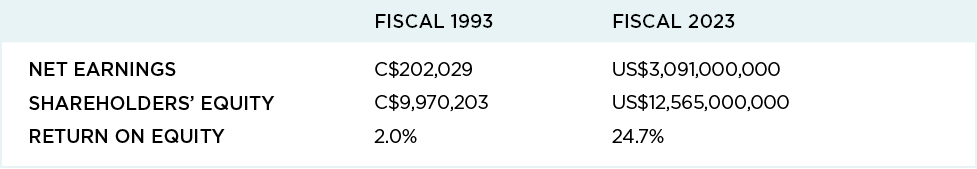

Consider a Canadian example. Alimentation Couche-Tard Inc., the owner of the Circle K convenience store chain, is a company we have owned off and on in our Burgundy Canadian equity portfolios, and consistently since 2016. From its origins as a single convenience store in Laval, Quebec in 1980, the company grew to 159 stores by 1994. Today, Couche-Tard has expanded to more than 16,700 stores in 29 countries. Over my 30-year investment career, the stock has gone up 265,000%, equating to a compounded return of 30% per year. Talk about compounding. As demonstrated in Figure 1, 30 years ago, Couche-Tard was earning a sub-par 2% ROE. Importantly, the company achieved an attractive mid-teens ROE two years later and hasn’t looked back since.

FIGURE 1

ALIMENTATION COUCHE-TARD FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS

Today, the company’s ROE is still above 20%, and the business remains extremely profitable. This profitability is being earned on a shareholder’s equity account that, having massively compounded, is many, many times bigger than it was 30 years ago (roughly US$12.6 billion today, up from just C$10 million 30 years ago). It has grown a whopping 1,700 times in 30 years. A business that can continue to earn a superior ROE, as the denominator that is shareholders’ equity continues to compound year after year, will be a wealth-compounding vehicle. Couche-Tard more than fits the bill.

So, all we need to do is to identify the compounders of the world, like Couche-Tard, in advance and own them. This approach is powerful and simple, but, unfortunately, not very easy. It is the “in advance” part that is so challenging.

Lesson 2: Face the Predictability Challenge

The second lesson involves the elusive nature of change, which makes predicting the future hard, if not impossible.

Take Hollywood as an example. In his 1983 classic Adventures in the Screen Trade,2 Willam Goldman wrote that, despite reams of market research, including various methods of audience analysis and focus groups, all used to protect the major investment dollars that go into producing a feature film, the vast majority of features lose money. “Nobody knows anything,” the screenwriter famously wrote, and it has become axiomatic. One of Goldman’s examples was the blockbuster Raiders of the Lost Ark. Passed on by every major studio but one, the film would go on to become a five-time Academy Award winner and one of the highest-grossing movies of all time. Adventures in the Screen Trade mentions another film in the George Lucas universe: Star Wars. Also rejected by all the major studios, Star Wars went on to spawn one of the most successful franchises in movie history, which Disney purchased for more than US$4 billion in 2012.

This predictability challenge appears in the venture capital industry as well, which runs under the assumption that a few “multi-baggers,” or large compounders, will make up for 90% or so of the investments that never pan out. Like pinpointing a box office smash, identifying compounding businesses in advance is tougher than it looks. Most startup companies don’t become profitable and eventually fail.

“While some may earn money for a few years before product obsolescence or competition bites, very few will earn money for decades.”

While some may earn money for a few years before product obsolescence or competition bites, very few will earn money for decades. And fewer still are those rare breeds, like Alimentation Couche-Tard, that earn superior ROEs and maintain them. While predicting the future may feel futile, and in some ways is, understanding the nature of change can help. Doing so requires appreciating a couple of things about change. One, it’s a sure thing and two, some things never change.

Change is a Sure Thing, but Some Things Never Change

Our lives 30 years ago were very different from today. Technological change has transformed our world. In 1994, almost no one used cell phones or the internet. If you asked to work from home, you would have been escorted out of the office, for good. Many changes come as a surprise. In 1994, a Kardashian was defending a former NFL football star in a trial widely watched on TV. Today, many are “keeping up” with some of his Kardashian descendants on a relatively new medium called social media. This would have been surprising (even unimaginable) 30 years ago.

Since changes and surprises are guaranteed, another way to help identify long-term compounders borrows from evolution. Charles Darwin suggested that it was not the strongest or the swiftest species that survived, but the most adaptable. Similarly, the companies most able to adapt, especially if situated in industries that change less than others, will be best positioned to survive and thrive, and potentially compound their owners’ wealth. Signs of adaptability include strong balance sheets and high profit margins, characteristics that build a margin of safety into a business and will help them respond to any negative surprises as their competitive situations evolve. Adaptability is a key tenet of what we call “quality” companies.

Just because change is inevitable, doesn’t mean everything changes. It’s important to remember that human nature never wavers, and our basic needs, wants, and emotions tend to stay the same. In our quest to discover long-term compounding businesses in advance, determining what won’t change is a good place to start.

For example, Warren Buffett regularly points out that the most popular candy bar in the U.S. is Snickers, just as it was 30 years ago, and 30 years before that. The legendary investor has said, “Our approach is very much to profit from lack of change rather than from change.”3

Consider our Couche-Tard example. While remaining nimble, Couche-Tard’s offering hasn’t strayed far from its original concept. What the company is really selling is time, and the time customers save is worth paying premium convenience store prices.

Will our collective time constraints, busyness, and need for convenience ever change? It hasn’t yet, and it seems like a reasonable bet to assume it never will. And Couche-Tard’s shareholders continue to benefit from the profitable sales their popular convenience stores generate. So, in our quest to discover long-term compounding businesses in advance, determining what won’t change is a good place to start.

Diversification is another advantage in a changing landscape. Because we cannot predict the future with any certainty, it makes sense to spread our bets. The objective is to put together a collection of ownership interests in a number of businesses that we believe are adaptable, very profitable, and likely going to be wealth-compounding vehicles. My 30 years of experience have also taught me that determining which specific companies will perform the best and worst over the long term will be a surprise. Still, if our overall judgment is good, and our selections are adaptable, high-quality businesses in industries that experience little change, a satisfactory compounded return can be expected.

Lesson 3: Be Patient

Most fortunes are accumulated over many years. That’s why the standard investment advice is to adopt a long-term time horizon. This too sounds simple but is not easy. Like heavyweight boxer Mike Tyson said, “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.”4

Sticking with a long time horizon is hard because it entails enduring an almost infinite number of short terms, when volatility, depressed business conditions, divisive politics, or even euphoria, can pull at our emotions. Let’s go back to my February 2, 1994 start date. Former U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan chose that day to surprise the market with the first interest-rate hike in five years. The U.S. economy endured a recession after the Savings and Loan Crisis of the late 1980s, and low interest rates were finally doing their job. The economy was growing again, and stock markets were moving higher. However, as the phrase “Don’t fight the Fed” would suggest, immediately after the Greenspan rate increase on my first day of investing, equity markets were volatile and challenging. It was one of many volatile short-term periods I would endure over the next 30 years.

Let’s go back to my February 2, 1994 start date. Former U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan chose that day to surprise the market with the first interest rate hike in five years. The U.S. economy endured a recession after the Savings and Loan Crisis of the late 1980s, and low interest rates were finally doing their job.

The economy was growing again, and stock markets were moving higher. However, as the phrase “Don’t fight the Fed” would suggest, immediately after the Greenspan rate increase on my first day of investing, equity markets were volatile and challenging. It was one of many volatile short-term periods I would endure over the next 30 years.

Since my tumultuous start date, we have witnessed many bouts of volatility. Some of the major ones include the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the dot-com bubble and subsequent wreck in 2000, the many bank failures and the global recession of 2007 to 2009, the very long and slow bull market of the 2010s, and the global pandemic of 2020. Yet since my start date, the S&P/TSX Composite Index is up 860% (or 8% compounded annually) and the S&P 500 Index is up about 1,650% (or 10% compounded annually) in Canadian dollars.5 While the U.S. market has done a lot better, investing in either or both markets would have led to wealth compounding, despite the regular volatility. And, fortunately, Burgundy has done better than the market averages over the long term.

In those moments of volatility and fear, it helps to appreciate what others have experienced. Remember that Buffett compounded so much wealth in his lifetime, despite wars, both hot and cold, pandemics, recessions, bank failures, social and cultural tumult, etc. How did he stick to his plan? With discipline. One of the many paradoxes of human nature is that we can be both overconfident and paralyzed by uncertainty at the same time. This works against our attempts to stick to a plan. Discipline can help us transcend these challenges. Discipline depends on our relationship with commitment. A necessary part of a commitment to compounding is adopting a long time horizon. The ideal time horizon is forever.

“One of the many paradoxes of human nature is that we can be both overconfident and paralyzed by uncertainty at the same time. This works against our attempts to stick to a plan.”

Committing to a disciplined approach entails following a code of behaviour. For example, investment discipline can mean committing to a simple rule, such as: I will maintain 75% of my wealth in stocks. Keeping this commitment will keep you invested, crucial when studies have shown that missing the 10 best days in the market over the past 30 years would have cut your return in half.6 Wow, talk about wreaking havoc on the compounding equation.

Sticking to a fixed percentage of investable assets in equities, like in our example, will also encourage you to rebalance when the percentage gets too far from the target. This will have you add to equity exposure on weakness, and trim on strength–both potentially good moves. With discipline, we can transcend our reptilian reactions and respond in accordance with our long-term plan. At Burgundy, our Investment Counsellors are here to ensure that our clients stay the course and benefit from the magic of compounding

Bonus Lesson: Change Compounds Too

My 30 years of investing have led to an approach that is simple, but not easy. We cannot know what’s coming. How will areas like artificial intelligence, climate challenges, future cold and hot wars, etc. change our world? No one can say for sure, especially since variables like these will interact with each other, further multiplying change. Wealth is not the only thing that compounds. Change compounds too. But one thing that doesn’t change is human nature.

The three big lessons from the first 30 years of my investing career demonstrate how commitment pays: In a world where changes and surprises are guaranteed, benefitting from the magic of compounding requires a commitment to patience. The direct result of us adopting this approach is a feeling of trust, trusting that, with a well-thought-out plan, our capital will be safe and compound adequately over the long term. Sounds like a nice place to be.

My late father-in-law used to say he was “too smart, too late.” And yes, it would be nice if I had known 30 years ago what I know today. But with the optimal time horizon being forever, I am better equipped today than when I started in 1994. The next 30 years start now.

Here’s to an even more successful next 30 years.

SPECIAL NOTE:

While this piece shares lessons from my 30 years as an investor, I would be remiss if I didn’t also acknowledge that in 2024, I’m celebrating another, even more important, milestone with my 30th wedding anniversary

References & Disclaimer

1. https://quoteinvestigator.com/2021/02/01/understand-exponential/

2. Goldman, Wiliam, Warner Books, 1983

3. https://www.businessinsider.com/warren-buffett-quotes-2011-4#the-lack-of-change-appeal-13

4. https://www.commit.works/everyone-has-a-plan-until-they-get-punched-in-the-mouth/#:~:text=When%20

Mike%20Tyson%20was%20asked,first%20contact%20with%20the%20enemy%E2%80%9D

5. Returns are from February 2, 1994 to December 31, 2023

6. https://www.hartfordfunds.com/practice-management/client-conversations/managing-volatility/timingthemarket-is-impossible.html

This post is presented for illustrative and discussion purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment advice and does not consider unique objectives, constraints or financial needs. Under no circumstances does this post suggest that you should time the market in any way or make investment decisions based on the content. Select securities may be used as examples to illustrate Burgundy’s investment philosophy. Burgundy funds or portfolios may or may not hold such securities for the whole demonstrated period. Investors are advised that their investments are not guaranteed, their values change frequently and past performance may not be repeated. This post is not intended as an offer to invest in any investment strategy presented by Burgundy. The information contained in this post is the opinion of Burgundy Asset Management and/or its employees as of the date of the post and is subject to change without notice. Please refer to the Legal section of this website for additional information.