In recent years, some new members of the Burgundy investment team have begun to find their voice through The View from Burgundy. David Vanderwood wrote this analysis of the checkered history of capital allocation at BCE, one of Canada’s flagship companies. He also worked in a theme that gets entirely too little attention – the supremely important nature of compounding and the radically damaging nature of negative returns.

– Richard Rooney, 2007

On a cold Montreal day in February 2000 at BCE Inc. headquarters, Jean Monty was making a tough decision. As head of the dominant local telephone company in eastern Canada, Mr. Monty felt like he was in a box. His business, while generating huge cash flow atop a natural monopoly, was a mature one. His shareholders, at least as he understood them, wanted growth. So, what to do?

The question was made even more challenging by BCE’s track record, where prior attempts to jumpstart growth via diversification had ended painfully. In 1989, the corporation bought a controlling interest in Montreal Trustco Inc., only to take a $500 million loss on selling it to the Bank of Nova Scotia in 1993. In that same year, management had also presided over the sale of BCE’s interest in Brookfield Development Corporation. This involved a $700 million write-off of another blunder from the 1980s.

Mr. Monty had asked one of his bright, up-and-coming financial analysts to prepare a report on those very transgressions. The conclusion was clear. Had Mr. Monty’s predecessors just left well enough alone, stuck to the core telephone business and used the excess cash flow to repurchase BCE shares, earnings per share would be almost 50% higher than their level at year-end 1999.

But, in Mr. Monty’s opinion, an organization couldn’t stand still or it would wither and die. It was harder than it sounded to just mine the cash flow out of a mature business. Top-notch talent might not stick around.

And the World Was Changing

At that time, giant global telecom behemoths were emerging, with names like WorldCom, Level 3 Communications and Global Crossing. They would have a huge scale advantage when they were finally able to get access to Canada’s residential customers. Following this reasoning, if Mr. Monty just stood pat, BCE would eventually be marginalized by massive competitors offering one-stop shopping, and doing so with a huge cost advantage. If there was a reasonable chance of this scenario playing out, something would have to be done. And soon.

Opportunity was knocking at Mr. Monty’s door. BCE already owned 23% of Teleglobe Inc. (the entity that prior to 1998 held a monopoly position on transferring international telephone traffic in and out of Canada) and was in a position to purchase the remainder. While this formerly good business was barely breaking even now that it was competing in a deregulated marketplace, it had something that BCE did not – an international network. At the end of 1999, Teleglobe had telecommunications licences or operating authorities in 27 nations, offices in 43 countries and connections with 450 carriers and 60,000 business customers. Buying Teleglobe would give BCE the platform upon which to build a global business that could compete with the big boys.

So, what was the downside? Yes, Teleglobe was burning through cash as it spent heavily to upgrade its global network so it could get in the game. And yes, the roaring bull market in technology and telecommunications stocks meant that Teleglobe’s global competitors had access to almost limitless supplies of equity capital that was almost free. Predictably, that was driving a massive gold rush to build out global high-speed telecom networks.

While fundamental economics would argue that too much supply of anything – even bandwidth – will eventually erode prices, bull market participants would hear none of it. Salomon Smith Barney analyst Jack Grubman once called a leading communications stock a buy “at any price” because, given the explosion in new applications that the Internet was driving, demand for bandwidth was infinite.

Mr. Monty made his decision. BCE’s purchase of Teleglobe for $10 billion was announced on February 16, 2000, just one month before the peak of the biggest stock market bubble in history. Timing is everything, as Teleglobe’s happy shareholders learned that spring. BCE shareholders would see the other side of the coin.

In his presentation to the investment community justifying the Teleglobe purchase, Mr. Monty made much of the boost in BCE’s revenue growth rate to 10% that buying Teleglobe would bring. Of course, that was looking out a couple of years. The day before the deal, Teleglobe released results for 1999 that included a 15% drop in sales.

And the World Did Change

Just two years later, a huge $7.5 billion write-down of Teleglobe led to Mr. Monty’s departure. What happened? Yes, demand for bandwidth and connectivity services kept growing, but far too many companies had chased the same market. And the free equity capital that was available to Teleglobe’s competitors added nuclear fuel to the competitive fire.

The ensuing massive build-out of global telecom network capacity knocked bandwidth prices through the floor. Fundamental economics had stood the test of time: too much supply of anything will drive prices down. How bad did it get? Teleglobe’s core voice and data business was sold to a vulture buyout fund for a mere US$125 million in May 2003. This equates to less than 2% of its “worth” just three years earlier.

What characteristics does the Teleglobe blunder share with BCE’s historical transgressions? Bell Canada has a long-term competitive advantage in its core local telephone business, but all of the strategic errors were to invest in businesses outside of this area, like real estate and financial services. Investing outside of one’s “circle of competence,” as Warren Buffett calls it, almost always ends badly.

Why do people insist on repeating the same mistake over and over? Part of the answer has everything to do with human nature. People are overconfident as a rule. Surveys suggest that 80% of us think that we are better than average drivers. To some extent this is necessary to deal with life, as studies have shown that the only people who assess themselves accurately in such areas as driving ability, appearance and sense of humour are the clinically depressed.

So-called “experts” are even more infected with overconfidence. Studies have shown that physicians ascribe a 90% confidence level to their initial diagnoses, but achieve only 50% accuracy. And trial lawyers at the outset of a case greatly overestimate their chances of winning in court.

“So-called “experts” are even more infected with overconfidence. Studies have shown that physicians ascribe a 90% confidence level to their initial diagnoses, but achieve only 50% accuracy.”

Business chief executive officers (CEOs) are no different. Despite reams of historical evidence that suggest that some 70% of mergers fail to create shareholder value, every executive who attempts one is confident that he or she will buck the odds.

The growth fixation of most public company managements is another reason they do deals. Instead of understanding the company’s true competitive strengths and then capitalizing on these strengths, countless CEOs pursue growth merely for growth’s sake. Making the company bigger tops the personal agendas of many CEOs. Refusing to acknowledge the economic limits imposed by the competitive capitalist system on the companies they run, many CEOs indulge their obsession with growth by trying to force it through acquisitions. Impatient executives become willing to assume the risk of severe capital loss in order to get to the finish line sooner. But long-term investors don’t have finish lines.

Consider this quote from the 1988 BCE annual report: “We are aiming for a steady annual improvement in earnings of five percent or more.” 1 This sounded good to us, until we went on to read: “To attain this, it is not sufficient to sit back and watch the various BCE companies go about their business. At the holding company level, we must manage aggressively the assets at our disposal in order to bring about earnings growth and an increase in share value.” 2 Of course, the aggressive actions taken the following year included the purchase of Montreal Trustco Inc. at the top of the cycle.

It is dysfunctional for shareholders to have a great business pass through all of its massive cash flow to a holding company run by “aggressive” executives. It is the rare manager at a parent company who is content to sit idly by and “watch the various BCE companies go about their business.” It is far more exciting to unleash the animal spirits within by doing deals. Of course, by pursuing sub-optimal investments, especially those outside of the core business, in the end the shareholders lose

An Investor’s Aim is to Compound Capital

Compounding capital steadily and regularly, even at a low rate, is ideal. Management action that impedes the compounding from a reliable business, whether by buying bad assets outside their “circle of competence” or by selling good assets within it, is the bane of a good investor’s existence. Unfortunately for its shareholders, BCE has done both.

What would have happened had BCE just stuck to its knitting since 1987 3 and concentrated on delivering the targeted 5% growth rate to shareholders? (Earnings from their Canadian telephone businesses actually grew at a compound annual rate closer to 6% over that time period.) We calculate that if management had used BCE’s free cash flow to repurchase shares, earnings per share would be more than double today’s level. The intrinsic value of BCE’s common shares would have gone along for the ride. Instead, management chose to subject shareholders to the risk of interrupting the compounding equation, or worse, suffering a significant capital loss by pursuing investments outside of BCE’s circle of competence.

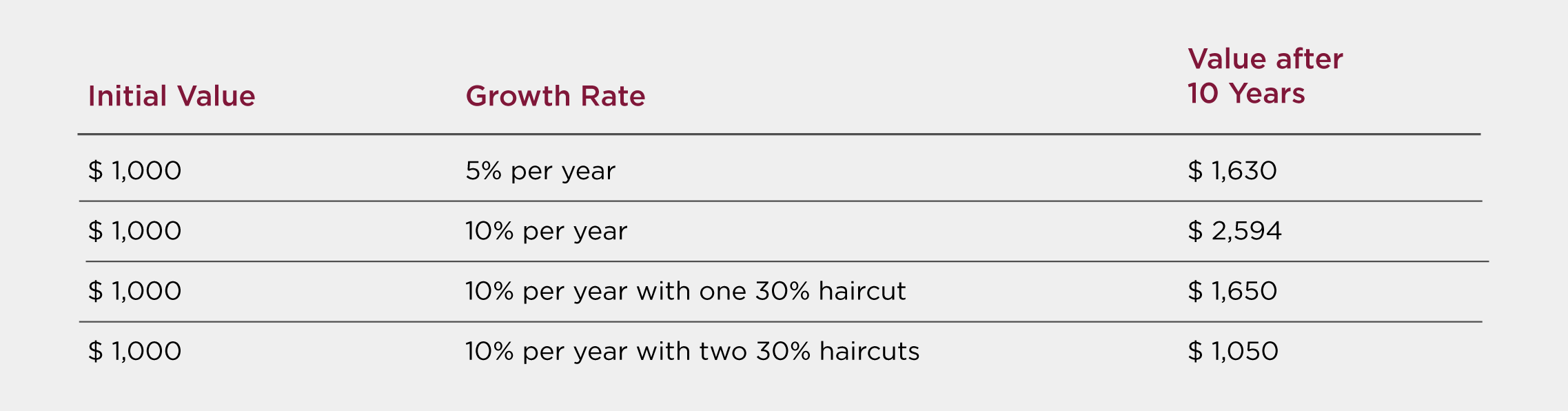

The achievement of even a modest 5% earnings growth rate over many years will drive substantial shareholder value. For example, $1,000 compounded at 5% over 10 years will grow to almost $1,630. Not bad! Of course, add dividends (BCE’s current yield is over 4%) and the total return can approach double digits. Pretty darn good when buying 10-year bonds will get you less than 5%.

“The achievement of even a modest 5% earnings growth rate over many years will drive substantial shareholder value.”

In addition, we think that there is a good reason why Warren Buffett’s number one investing rule is to never lose money (and why rule number two is: don’t forget rule number one!). Losses greatly inhibit the compounding of capital.

Consider our 5% compound interest example in the table below. If we were able to juice up the compound growth rate to 10%, the value of $1,000 after 10 years would obviously be far greater – almost 60% higher in fact. But, including only one year with a 30% negative hit would knock the compound result back to exactly the 5% level. And subtracting two 30% haircuts from an otherwise 10% positive annual rate virtually eliminates any growth over the entire decade.

Negative Numbers Wreak Havoc on Compounding Equations

The best investors understand this sombre fact and look for management teams who will not expose them to negative shocks. But the massive capital misallocation mistakes we too frequently observe suggest that many executives just don’t get it.

Outstanding managers know where to draw the line. Much like integrity, which author Flannery O’Connor defined in her 1952 classic novel, Wise Blood, to mean what you won’t do, excellent executives simply won’t risk shareholder’s capital on inappropriate adventures that could upset the compounding equation.

This is not to say that risk-taking has no place in our economy. Far from it. Risk-taking is the essence of wealth creation in our capitalist system. But executives at mature, cash-generating companies are not running venture capital funds where large numbers of investments are made in the hopes that a few huge paydays will occur and make up for the majority that turn out to be losers.

When dealing from the position of strength that an established competitive advantage brings about, the appropriate risk-taking actions are those of a “blocking and tackling” nature. Relentless focus on the core business and on executing a business plan that exploits strong positioning will yield good returns to shareholders. Slow and steady wins, especially when running a mature, well-positioned firm.

Executives should pursue strategies that maximize the long-term profitability of businesses with sustainable competitive advantages. Furthermore, companies should only invest in these businesses if the expected return surpasses a reasonable estimate of the company’s cost of capital. This is effective capital allocation.

Ineffective Capital Allocation Will Disturb the Compounding Miracle

Any BCE executive could have saved shareholders a bundle by asking himself one simple question: “Did BCE have a sustainable competitive advantage in offering global telecommunications services (Teleglobe), real estate (Brookfield) or financial services (Montreal Trustco)?” The answer was no. It brings to mind the world champion chess player’s advice when asked how to avoid making a bad move. His answer: “Sit on your hands!”

We have a sneaking suspicion that, much like the avoidance of disastrous acquisitions that sticking to one’s knitting entails, success from insisting on earning a decent return on allocated capital will come largely from those ill-advised moves that don’t get done. We call it maintaining strategic integrity.

So when new CEO Michael Sabia publicly stated that BCE’s new strategy was one of simplification where the only focus would be the core telephone business, we applauded. Maintaining strategic integrity is always step one. We have confidence that Mr. Sabia and new board Chairman Richard Currie embrace this. Indeed, having these two superior executives in charge was a key reason we purchased BCE shares for the first time in 2002. We still own them.

However, the new BCE executive team did make another profound mistake. They sold one of BCE’s crown jewels – a business with terrific compounding qualities that was well within their circle of competence. Perhaps they felt backed into a financial corner at an inopportune time. They were forced to unwind another past mistake by repurchasing 20% of operating company Bell Canada from SBC Corporation. SBC had bought its Bell stake in 1999, and with it came an option to sell it back to BCE in 2002 at a 20%-plus premium. With global telecom valuations at bear market lows, SBC decided to exercise their option. This forced BCE to come up with $6.3 billion fast.

The fall of 2002 was a tough time to arrange financing given the liquidity crisis that had taken over global financial markets, but BCE did an admirable job. Large bond and equity issues were completed and asset sales were studied. Unfortunately for long-term shareholders, the long line-up of buyers for their Yellow Pages directories business compelled BCE to offload it.

The Bell Yellow Pages is one of the best businesses in Canada. As the fifth-largest Canadian public media company, it has a 93% market share with a renewal rate over 90%, as well as 58% cash flow margins. While growth is slow (sales growth has compounded at 2.6% over the past decade – profit growth has been faster because of operating leverage), it requires almost no capital. For example, at other good free cash flow businesses such as radio and TV broadcasters, capital expenditures consume about 15% of operating cash flow. Directories consume less than 3%. As a result, over one-half of every revenue dollar is available for distribution to shareholders. Having a so-called free cash flow margin north of 50% ranks up there with the best assets in the world.

One way to value a stable and increasing cash flow stream is to treat it like a growing perpetual annuity.4 Yellow Pages generated about $355 million in pretax free cash flow in 2003. If one uses an 8.5% discount rate along with only a 2% growth rate, the pretax value of the annuity comes to almost $5.5 billion. BCE sold Yellow Pages for $3 billion to a financial consortium that subsequently flipped it out to the public as an income trust. While taxes complicate the matter somewhat, note that Yellow Pages Income Fund today sports a $5 billion enterprise value. Keeping this asset in-house should have been the only option. Dominant franchises with growing free cash flow streams are scarce, and BCE could easily have handled more debt. Selling it for $3 billion was a major misallocation of capital that hurt shareholders’ compounding aims.

An investor’s goal is to compound capital. Management action that impedes the compounding from a reliable business, whether by buying bad assets outside their circle of competence or by selling good assets within it, is bad for shareholders. CEOs who instead embrace strategic integrity can generate substantial wealth. Even a small positive number compounded for many years turns into a very large number. That is why in the investment business the magic of compound interest is known as the eighth wonder of the world.

1. BCE, Annual Report, 1988

2. BCE, Annual Report, 1988

3. This date was selected because that is as far back as our annual report library goes. It encompasses enough history to make our point.

4. Valued using a dividend discount model where

V = D/(R – G); V = Value, D = Dividend, R = Discount Rate, G = Growth Rate of Dividend.

This post is presented for illustrative and discussion purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment advice and does not consider unique objectives, constraints or financial needs. Under no circumstances does this post suggest that you should time the market in any way or make investment decisions based on the content. Select securities may be used as examples to illustrate Burgundy’s investment philosophy. Burgundy funds or portfolios may or may not hold such securities for the whole demonstrated period. Investors are advised that their investments are not guaranteed, their values change frequently and past performance may not be repeated. This post is not intended as an offer to invest in any investment strategy presented by Burgundy. The information contained in this post is the opinion of Burgundy Asset Management and/or its employees as of the date of the post and is subject to change without notice. Please refer to the Legal section of this website for additional information.