Before institutional investors dominated the investment landscape, most public-company shareholders were individuals who owned their stock directly. The human identity of these shareholders was an important underlying principle of capital formation in the mid-1900s. Stockholders were truly viewed as “owners” of the business rather than a mere paper claim on residual earnings. This concept had both economic and political motivations: it promoted growth of the middle class and aligned the interests of ordinary citizens with the success of their domestic economy.1

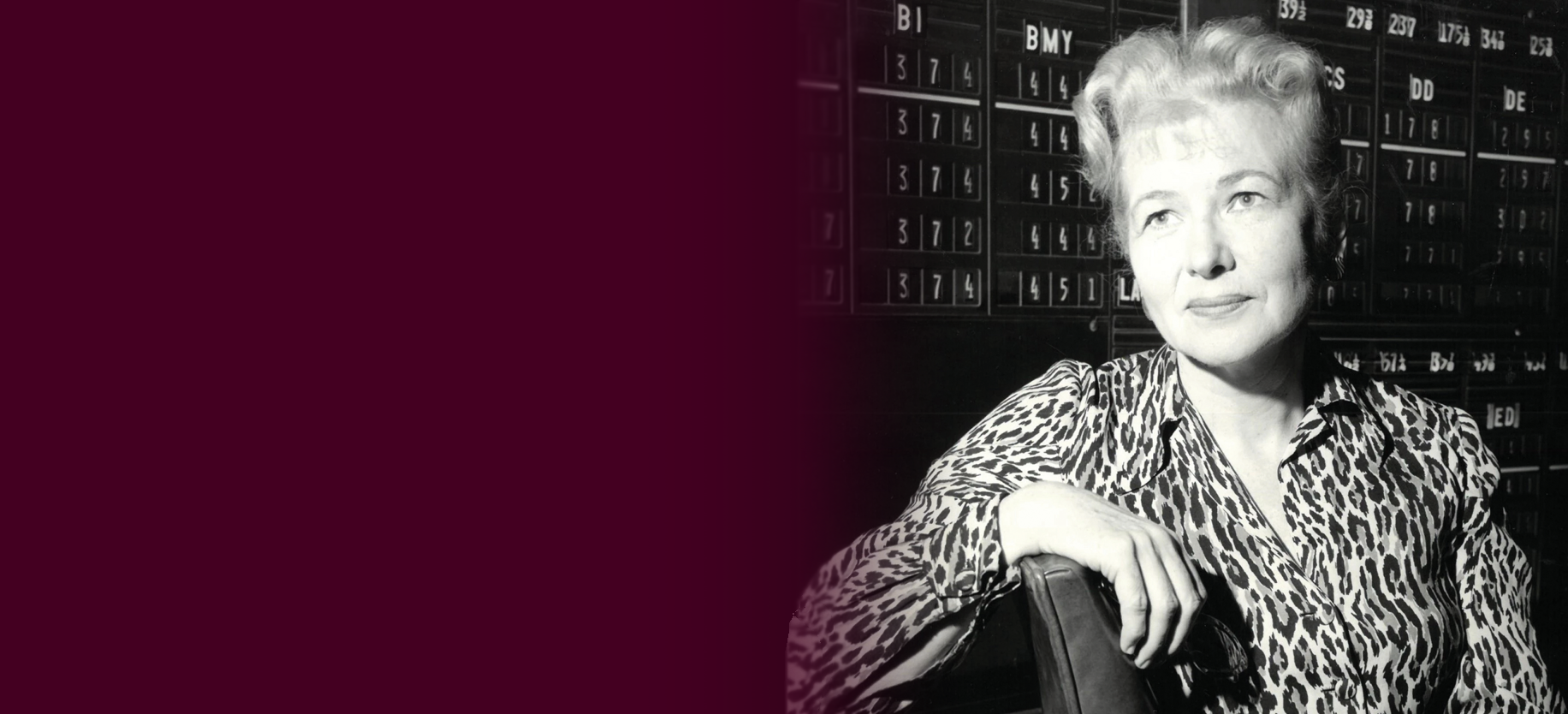

In 1945, Forbes hired 45-year-old American public relations consultant Wilma Soss to conduct a study about individual stock owners. The resulting article, titled “Business Women are Here to Stay,” would become the first act in Soss’ 40-year career as a prominent shareholder activist and champion of women’s economic rights. She uncovered a revelation that shocked her contemporaries: women, it turned out, represented the largest cohort of stockholders across many of the largest companies in America. The likes of AT&T, Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, General Electric, General Motors, CBS, NBC, and the majority of the companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange could have been called “women-owned enterprises” in today’s parlance.2 In stark opposition to their ownership, women’s representation on management teams and corporate boards was nearly non-existent.

Soss would spend the rest of her life working to ameliorate this inequity. She argued that companies should serve their shareholders and pay attention to the interests of owners, even if those owners were women. She also reasoned that women should be represented on corporate boards and management teams, particularly if women represented more than half of a company’s shareholder base. At a time when women were often excluded from the workforce altogether, Soss became one of the first leaders of the women’s economic suffrage movement.3

To organize and advance her advocacy, Soss founded the Federation of Women Shareholders in American Business. The federation leveraged women’s existing participation as owners within capital markets to make a case for broader involvement in governance and management. In addition to facilitating a coordinated appeal for equity, the group leveraged the power of the proxy vote. Soss would aggregate members’ proxies to support shareholder motions that nominated women to directorship positions. If more women could be elected to the highest executive roles in America, then women’s participation in the workforce could gain greater acceptance and prominence. The federation could use proxy voting as a tool to force change if it didn’t come freely.

Soss used her eccentric personal style to draw headlines and reach a broader audience. She eventually earned a reputation for being “the liveliest and most combative lady capitalist we know,” as characterized by New Yorker magazine in 1954.

“She argued that companies should serve and pay attention to the interests of owners, even if those owners were women.”

A few anecdotes from Soss’ career stand out as particularly memorable:

- In 1947, she attended the annual general meeting (AGM) of U.S. Steel, which had majority female ownership at the time. She challenged Chairman Irving Olds about the absence of female representation on their board of directors. Her call to action pointed out that “women are not represented in a company which is financed by their capital, and which does business in an economy where women have plurality of the vote.”

- In 1949, she showed up (again) to the U.S. Steel AGM in full Victorian garb to underscore the company’s old-fashioned and patriarchal attitude. Wearing a large purple hat, she stated that “this costume represents management’s thinking on stockholder relations.”

- In 1966, she went to a Ford Motor Company AGM wearing a crash helmet and medieval armour to nominate vehicle-safety activist Ralph Nader to the board of directors.4 Not all of Soss’ activism was exclusively focused on women’s issues. She argued for the interests of minority shareholders more generally, including issues related to consumer safety.

Although her tactics were creative, her objectives were clear and serious: she wanted to advance minority shareholder rights by increasing corporate transparency and access; demonstrating the active role that even small investors could play in corporate governance; and electing more women to corporate boards.

To increase transparency and access, she lobbied for the physical location of investor meetings to be held in widely accessible and well-publicized venues. Before Soss, AGMs were often held in deliberately obscure places to deter minority owners from engaging with company management. To demonstrate the active role that small investors can play in corporate governance, she would challenge directors and CEOs on executive compensation and dividend policies. In typical Soss style, she once showed up to a New York Central Railroad AGM in bare feet, lamenting that the company’s dividend wasn’t high enough to afford her a pair of shoes. To promote the inclusion of women on corporate boards, Soss would recruit talented women who could succeed as directors, then propose their nomination in upcoming proxy circulars.

While Soss was reasonably successful in her effort to increase transparency and demonstrate minority shareholder engagement, she was less successful in getting more women on boards. One chairman responded to her entreaties by saying that women may indeed be of assistance to their board—if the issue of interior decorating was ever on the agenda. Today, board diversity remains a work in progress. Over the past few years, changes in reporting standards across Canada and the U.S. continue to build upon the legacy of Wilma Soss’ federation. Most recently, the Nasdaq made it mandatory to report how many women and diverse candidates are on public company boards5 that are listed on their exchange. In Canada, we have “comply or explain” legislation6 which requires issuers to demonstrate some level of inclusion for women and other minority groups—or be forced to answer the question that Soss posed to the board of U.S. Steel 75 years ago: “Why isn’t there a woman on the board of directors?”

1 Of course, the corollary implication was to pit the interest of ordinary Americans against the rising threat of command economics that was emerging internationally.

2 Hann, Sarah. “Corporate Governance and the Feminization of Capital.” Stanford Law Review (Vol 74, Issue 3). March 2022.

3 In the years following the Second World War, there was concern among some men that the jobs they held before the war would be lost to a new wave of working women, who had filled domestic employment gaps in wartime. Consequently, there was pressure on executive management teams to fire working women and re-hire returning veterans.

4 Not all of Soss’ activism was exclusively focused on women’s issues. She argued for the interests of minority shareholders more generally, including issues related to consumer safety.

5 As of August 2021, boards of directors of most Nasdaq issuers, including Canadian issuers, are required to include at least two diverse directors, one of whom must be female, under bold new rules approved by the SEC. Nasdaq becomes the first regulator in the world to mandate diversity beyond gender on public company boards with its requirement that U.S. issuers must have at least one director who is from an underrepresented minority. Nasdaq’s new progressive board diversity listing requirement

6 Effective Jan. 1, 2020, corporations governed by the Canada Business Corporations Act with publicly traded securities arewill be required to provide shareholders with information on the corporation’s policies and practices related to diversity on the board of directors and within senior management, including the number and percentage of members of the board and of senior management who are women, Aboriginal persons, members of visible minorities and persons with disabilities. Canada is first jurisdiction worldwide to require diversity disclosure beyond gender

This post is presented for illustrative and discussion purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment advice and does not consider unique objectives, constraints or financial needs. Under no circumstances does this post suggest that you should time the market in any way or make investment decisions based on the content. Select securities may be used as examples to illustrate Burgundy’s investment philosophy. Burgundy funds or portfolios may or may not hold such securities for the whole demonstrated period. Investors are advised that their investments are not guaranteed, their values change frequently and past performance may not be repeated. This post is not intended as an offer to invest in any investment strategy presented by Burgundy. The information contained in this post is the opinion of Burgundy Asset Management and/or its employees as of the date of the post and is subject to change without notice. Please refer to the Legal section of this website for additional information.