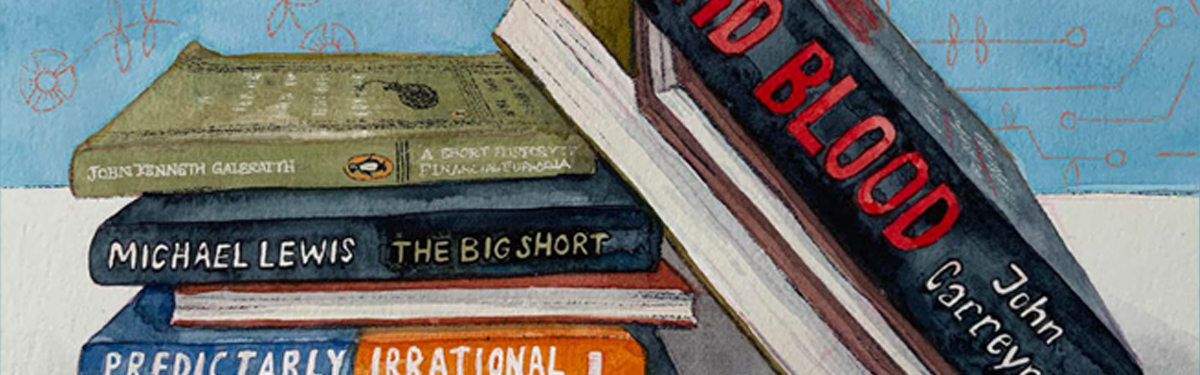

Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup by John Carreyrou

Investors are constantly faced with compelling stories about early stage companies claiming to be “disruptors,” re-writing the rules of the industry in which they operate. Disruptors claim to offer a simpler, cheaper or more convenient alternative to an existing product or service. Well known examples include; Uber forever changing the taxi industry, Airbnb redefining hotel accommodation, and Netflix’s entry into the at-home entertainment industry. While some early stage companies go on to become very viable businesses, the reality is, the majority do not.

Theranos, was a private healthcare technology firm founded in 2003 by then 19-year old, Elizabeth Holmes. Holmes had dropped out of Stanford to pursue what she saw as a significant opportunity to completely transform the blood testing industry. Her company claimed to have developed technology to run hundreds of tests on a small drop of blood drawn from a single finger prick. It was further asserted that the blood would be analyzed in just a few minutes, providing accurate test results on the spot. These key changes to blood testing, if successful, would significantly reduce costs, normalize the use of this type of blood test, and increase the frequency of early detection of disease.

After years spent quietly researching and fundraising, Theranos launched its technology to the public in 2012. The company formed a partnership with U.S. grocery chain Safeway, with the plan to retrofit 800 stores with Theranos blood-testing clinics. One year later, Theranos was successful in forming a similar partnership with drugstore chain Walgreens, to open blood-testing centres in over 40 of its locations. The momentum continued to build. Theranos raised more than US$700 million from venture capitalists and private investors. At its peak in 2013, the company was valued at US$9 billion. Elizabeth Holmes had become a household name in the U.S., appearing on the covers of Forbes and Fortune magazines in 2014.

What investors and the public didn’t know, however, was that Theranos’ technology was flawed, and the test results were unreliable. The turning point happened in October 2015, when investigative journalist, John Carreyrou, published an article in the Wall Street Journal questioning Theranos’ technology and exposing the lies.1

Theranos is one of the most widely publicized frauds in U.S. history because of the potential for misdiagnoses that could ultimately lead to harm or death. The rise and fall of Theranos has been documented not just in John Carreyrou’s book, but also in the HBO documentary “The Inventor”,2 and on the front pages of newspapers.

The Lure of a Compelling Story

Many startup companies market a compelling story of being disruptors with tremendous growth potential. In the case of Theranos, the founder told an emotionally captivating story of how the new technology could detect illnesses very early, including one of the worst, cancer. By placing this technology in people’s homes or nearby pharmacies, Holmes promised individual empowerment over one’s health at an affordable cost.

Board members such as Former U.S. Secretary of State George Shulz, Former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and U.S. Secretary of Defense General James Mattis, were drawn by Holmes’ “visionary” story focusing on the human right to affordable and timely access to diagnostic testing. The involvement and support of these influential people provided credibility to the company, irrespective of the fact that they had no expertise in biotechnology.

The media was initially complicit in helping to retell this captivating story. Their validation of Holmes’ vision and the company’s ability to execute according to it, resulted in an enormous sense of public and investor belief in Theranos. Blind trust overrode any instinct to look for evidence of validation of the technology by the medical community.

John Carreyrou helped us understand what drove decision making at the companies that partnered with Theranos. As he described in his book, the partnership was rationalized through flawed judgement, guided by the “fear of missing out.” When problems with the Theranos technology were pointed out to the executive at Walgreens leading the partnership, he answered, “We can’t not pursue this. We can’t risk a scenario where CVS has a deal with them in six months and it ends up being real.”

In hindsight, there were many issues at Theranos that a careful due diligence process would have revealed. For example, a simple check of Theranos’ Glass Door profile (a website that allows employees to anonymously rate and review their companies) would have found several red flags. A former Theranos employee shared the following comment: “How to make money at Theranos: Lie to venture capitalists, doctors, patients, the FDA and the government. Commit highly unethical, and possibly illegal acts.”3

So, what are the investment lessons from the study of the rise and fall of Theranos? There are many, but perhaps the most important is to simply be mindful of the human behavioural tendency to subordinate reason to emotion. If we understand and remember this, careful due diligence and discernment will guide us to better decisions. As Dan Ariely, Professor of Psychology and Behavioural Economics, and author of last year’s Book Club selection Predictably Irrational, states, “Data doesn’t sit in our minds like stories do. Stories have emotions while data doesn’t. And emotions get people to do all kinds of things, good and bad.”2

1. “Hot Startup Theranos Has Struggled With Its Blood-Test Technology,” 2020. May 24, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/theranos-hasstruggled-with-blood-tests-1444881901

2. “The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley,” 2020. May 25, 2020. https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Inventor:_Out_for_Blood_in_Silicon_Valley

3. “Theranos Reviews,” 2020. May 25, 2020. https://www.glassdoor.ca/ Reviews/Theranos-Reviews-E248889.htm

This post is presented for illustrative and discussion purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment advice and does not consider unique objectives, constraints or financial needs. Under no circumstances does this post suggest that you should time the market in any way or make investment decisions based on the content. Select securities may be used as examples to illustrate Burgundy’s investment philosophy. Burgundy funds or portfolios may or may not hold such securities for the whole demonstrated period. Investors are advised that their investments are not guaranteed, their values change frequently and past performance may not be repeated. This post is not intended as an offer to invest in any investment strategy presented by Burgundy. The information contained in this post is the opinion of Burgundy Asset Management and/or its employees as of the date of the post and is subject to change without notice. Please refer to the Legal section of this website for additional information.