No Country for Old Rules

Rules give structure to our world, but what happens when they no longer serve us?

In this View from Burgundy, Portfolio Manager David Vanderwood reflects on the evolution of his investment approach, sharing what he’s learned, what he’s unlearned, and how a movie hitman inspired an unlikely epiphany.

KEY POINTS

- When the rules no longer apply, it’s time to rethink your approach.

- True safety comes from owning high-quality businesses that can endure across market cycles.

- Quality plus value is where compounding can thrive.

- Investing success depends on staying curious.

Clarity often arrives unexpectedly. It’s usually less about where the message is coming from and more about whether you’re ready to hear it. As the old saying goes, when the student is ready to learn, the teacher will appear. In late 2007, I was primed.

I was sitting in a movie theatre watching the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men. Set in 1980s Texas, the Western thriller follows a Vietnam veteran who stumbles upon a drug deal gone wrong. Against his better judgment, he pockets the cash left behind, a whopping $2 million, and quickly becomes the target of Anton Chigurh, a merciless hitman played by Javier Bardem. With his bowl cut and bolt pistol, Chigurh ranks among the most memorable villains in modern cinema. When another bounty hunter joins the chase for the money, Chigurh ambushes him in a hotel room and, with chilling calm, asks him, “If the rule you followed brought you to this, of what use was the rule?” Moments later, he pulls the trigger.

Something about what the psychopathic, yet principled, villain said rang true. As soon as the credits rolled, I headed for the door. Minutes later, I was in line at a nearby bookstore, ready to devour the Cormac McCarthy novel the film was adapted from.

What Did All the Rules Add Up To?

When the film No Country for Old Men was released back in 2007, the investment world was on the precipice of change. The Global Financial Crisis was on the horizon, and the traditional value investing mindset I carried with me from school was being tested. Back then, I’d been taught to buy companies that looked “statistically cheap,” meaning their stock price looked low compared to how much they earned or what their assets were worth. This technique was based off Ben Graham’s approach. However, while the father of value investing incorporated intrinsic value and a margin of safety into his framework (principles that still help guide Burgundy’s approach today), this shortcut focused mainly on the price. It captured the cheapness side of value but overlooked its deeper substance and many of Graham’s finer points.

By 2007, the old “cheap” playbook was breaking down, and the investing community faced a collective reckoning. For those whose careers had been built on companies that looked cheap on paper, it was time to think again. For me, it was a moment to re-evaluate the lessons and formulas I’d been taught and to truly appreciate the long-term compounding power of great businesses in a way I hadn’t before. I watched a tried-and-true method become less tried and less true. It’s no wonder Chigurh’s question left such an impact on me. What did all these rules add up to if they no longer worked?

In this View from Burgundy, I will reflect on the evolution of my investment approach, tracing the path from my university days to how I think about quality and value today.

Lessons From UBC PMF

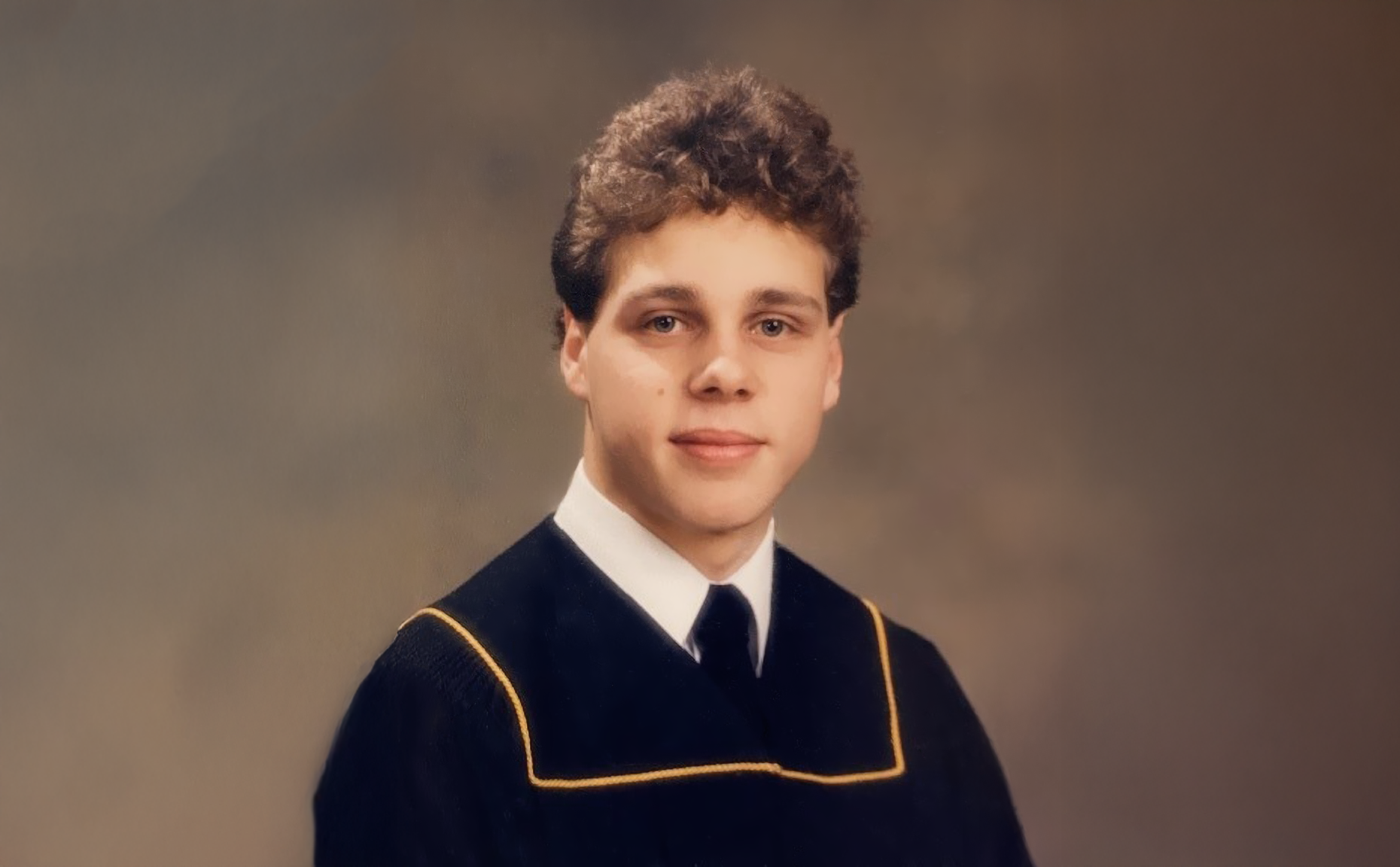

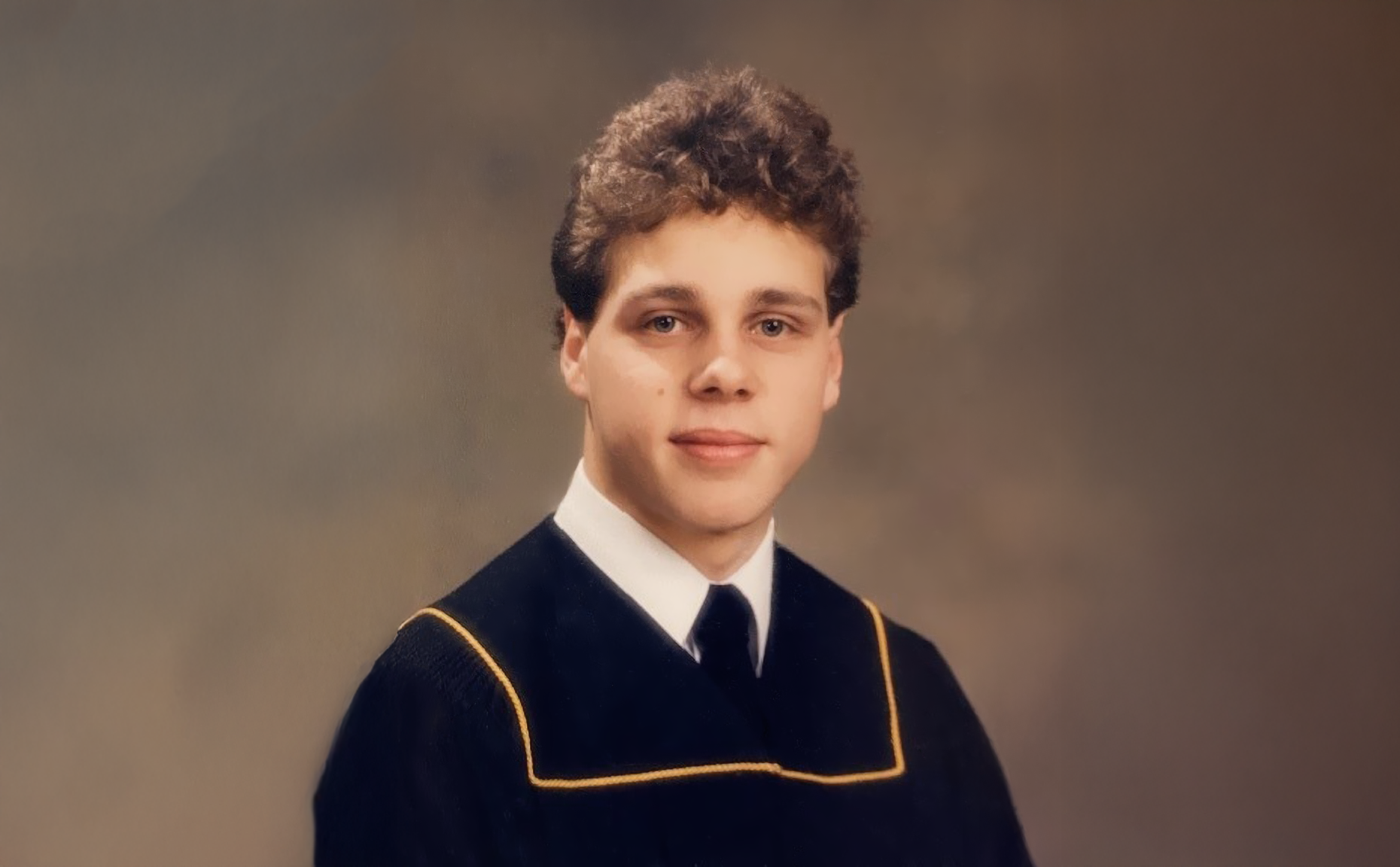

Long before Bardem brandished his bowl cut on the silver screen, I was training to be a traditional value investor.

It was the early ’90s. Nirvana had exploded out of Seattle, and I was just a couple of hours’ drive away in Vancouver, enrolled in the University of British Columbia’s Portfolio Management Foundation (PMF) course. The grunge scene was in full swing—“Smells Like Teen Spirit” was all over the radio, and everywhere I looked people in plaid flannels and slouchy cardigans were channeling their inner Kurt Cobain. I was still shaking off a decade “lost” to teenage exploration. A student of investing, my initial foray into this field hadn’t exactly gone as planned—the first stock I bought had already gone bankrupt. I knew I had a lot to learn. It was during my studies in the PMF program that I first discovered Graham’s approach to value investing.

As I mentioned, Graham’s investment philosophy was reduced to something straightforward but powerful: figure out what a company is really worth (its intrinsic value) and buy only when the price is significantly lower. Graham called this gap between price and value the margin of safety—the cushion that protects you if things go wrong. To determine the intrinsic value, you gathered the data, made assumptions, tested the minimum return that would make the investment worthwhile, ran the numbers, and poof! It was like cracking a code. I built a portfolio of these “value” investments and sold them once they reached intrinsic value, repeating the process again and again.

Some people are born appreciating the value of a dollar and are always on the lookout for bargains. Maybe it’s being frugal, or maybe it’s just being a cheapskate. Regardless, I was definitely one of those people, and this just-buy-what’s-cheap approach to value investing suited my scarcity mindset. I loved the clarity of the formula. If a business was worth “x” and I could buy it for 60% of that, then I could just wait until it climbed back to “x” and sell. Back then, it felt like the investment world was certain and predictable. Now I know better.

It Worked (Until it Didn’t)

While this approach on its own worked for a long time, it’s important to appreciate that these cheap investments were cheap for a reason. They were often plagued by “issues” or riddled with controversies. For instance, a loss-making segment overshadowing a strong underlying business, a major management move sparking uncertainty, or an ill-timed acquisition rattling confidence. Despite these risks, prominent value investors like Martin Sosnoff encouraged others to buy these cheap stocks. In his 1997 Forbes article, “If it Ain’t Controversial, Don’t Buy it,” Sosnoff argued that controversial “issue” stocks were often mispriced because many investors avoided the anxiety that came with owning them.1

Importantly, as Graham suggested decades earlier, diversification was key. If you owned enough of these “issue” stocks, you could spread out the individual risks of each one.

And yet, a decade after Sosnoff’s article was published, value investing was entering a new phase, one in which the conventional value investing I had been taught began to lose its edge. Buying cheap stocks worked, until it didn’t. As the investment firm GMO highlighted in its 2024 white paper, “Beyond the Factor,” from the 1920s through 2006, value outperformed growth by nearly 5% per year.2 After 2006, there was a shift. You could no longer simply buy cheap stocks and expect superior performance. That traditional value approach began underperforming.

“Back then, it felt like the investment world was certain and predictable. Now I know better”

Too Much Information & Tougher Competition

Over the years, we’ve gone from being starved of information to being completely overfed, and this information buffet is partly to blame for the breakdown of traditional value investing. When I started investing, information was scarce. Annual reports arrived by mail, conference calls were rare, and brokerage analysts’ reports were paper-based and released sporadically. Because companies controlled the transmission of information, they determined not just what data was released but also when. That pre-internet environment was well suited for restrained value investors, and patience paid off. Today, we’re drinking from an information firehose. The challenge is no longer finding information but filtering out the noise. Philosopher William James’ sage advice is now apt: “The art of being wise is knowing what to overlook.”

The competition also got tougher. When I was a student in the ’80s and ’90s, business degrees weren’t nearly as coveted. But once the word got out that hedge funds were lucrative, many of the best and brightest flocked to finance, armed with better training and sharper tools. At the same time, disruption risks grew. As the cost of technology fell, entrepreneurs began launching start-ups from their garages, eager to eat the lunches of established companies. Many “cheap” stocks often turned into value traps—attractive on the surface but masking deep problems that would lead to intrinsic value erosion. Careful research became the only defence.

Together, these forces undermined the advantage that traditional value investors once enjoyed. And then something else shifted—something even more fundamental.

“Today, we’re drinking from an information firehose. The challenge is no longer finding information but filtering out the noise.”

When Trees Grow to the Sky

For centuries, big companies slowed as they grew, rewarding value investors who could profit by assuming that sales and earnings would “revert to the mean” or to a “base rate” of growth that was not too fast. Starting in the early aughts, however, a few U.S. technology giants broke the mold. The internet allowed early movers to capture markets and build winner-take-all positions, sustaining growth and returns on capital at levels that history would have deemed unsustainable. They seemed unmoored from gravity. At Burgundy, we often remind ourselves that trees don’t grow to the sky. This helps keep us grounded and focused on our long-term, quality/value approach.

However, it seemed like that’s what was happening. Companies like Alphabet (Google), Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon kept compounding far beyond traditional limits. They just kept growing. These early movers grabbed markets, scaled rapidly, and built near-monopoly positions in winner-take-all industries. Some are still growing through thoughtful expansion into adjacent markets. Alphabet, for instance, first dominated search and advertising, then went into adjacent markets with products like YouTube and Google Cloud. When Alphabet acquired YouTube in 2006, it was a much smaller platform that has since scaled significantly. Today, the company has 15 products with over half a billion users each and seven with over two billion users. It is still seeing strong growth and trading at a reasonable valuation. We continue to hold Alphabet, alongside Microsoft and Amazon, in our U.S. equity portfolio.

In this new era, investors (myself included) better appreciated the power of compounding. In 1982, the year before the internet’s birth, IBM was the world’s largest company at US$32 billion. Today, Nvidia is worth over $5 trillion, Apple and Microsoft are each around $4 trillion, Alphabet exceeds $3 trillion, and Amazon surpasses $2 trillion (in U.S. dollars).

This is where traditional value investing lost its edge. Solely selling when a stock reached intrinsic value often meant walking away from the very businesses that went on to keep compounding—the long-term winners that just kept growing, the ones this framework wasn’t built to capture.

“This is where traditional value investing lost its edge. Solely selling when a stock reached intrinsic value often meant walking away from the very business that went on to keep compounding.”

Reassessing Quality

My moment of clarity led to deeper introspection. Back to Chigurh’s question: “If the rule you followed brought you to this, of what use was the rule?” For me, the answer wasn’t to abandon value investing—far from it—but to rethink the rules and broaden my definition. Quality was already gaining prominence in Burgundy’s investment approach. I had to figure out how to emphasize it further in my process, pairing it alongside the importance of value. This transition didn’t happen right away. Like Steve Jobs said in his famous 2005 Stanford Commencement Address, “You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards.”3 My former partner and mentor at Burgundy, Allan MacDonald, was instrumental in my adaptation. He kept pointing out companies he had once owned that had since grown a lot larger and a lot more valuable. His self-flagellation was telling me to better appreciate the potential of compounding.

What is quality?

Quality can be an elusive concept, but at its core it means meeting high specifications and exhibiting excellence relative to peers. In investing terms, quality companies are those with both quantitative strengths—such as profit margins, returns on equity, and growth rates—and qualitative ones like management, capital allocation skills, and company culture. Essentially, quality companies stand out for their durable competitive advantages, both economic and operational, and their ability to deliver sustained, long-term growth.

Why does quality matter?

The more I learned about the benefits of investing in quality over simply value, the more interested I became. After the bargain hunter’s value playbook began breaking down, it became clear to me that buying “cheap” was no longer enough. I needed a more balanced approach, pairing quality with value. Investing in quality helps reshape the risk-reward equation. Burgundy’s definition of quality companies insists that they are, at minimum, growing intrinsic value. Strong businesses with solid balance sheets provide downside protection, reducing the likelihood of permanent loss of capital. If, on occasion, a selected business begins to mature and decline, a quick sale is the correct response.

Focusing on quality also filters out the weaker businesses that may appear cheap but erode value over time. Investors who can avoid these so-called “value traps” can sidestep a costly mistake. Applying this filter also means you’re making fewer decisions in general. With the value investing approach I learned at UBC’s PMF course, an investor had to be right three times: when you buy, when you sell, and when you reinvest the proceeds from the sale. More decisions increase the odds of making a mistake.

And, most importantly, quality enables compounding. Companies with durable advantages have the greatest potential to compound capital over time. A weaker business might make money for a while, but eventually competition squeezes margins or growth runs out of steam. A high-quality company with durable advantages—like loyal customers, a powerful brand, cost efficiencies, and an expanding value proposition—can protect its profits and keep finding new ways to grow. Take one of Burgundy’s portfolio holdings, Alimentation Couche-Tard, which I highlight in more detail in my previous View, “3 for 30.” Over the past 30 years, it has repeatedly reinvested its earnings into acquiring and improving convenience stores around the world. Because it had the management skill, scale advantages, and culture, Couche-Tard turned modest beginnings into one of the great Canadian compounding stories. Its value increased by 250,000% over 30 years, a powerful demonstration of the wealth-creating power of compounding.

“Quality companies stand out for their durable competitive advantages, both economic and operational, and their ability to deliver sustained, long-term growth.”

How do you find high quality?

True high-quality compounders are rare. The challenge isn’t just about finding them today; it’s predicting which ones can keep compounding for the next decade and beyond.

First, they are already doing it: growing their revenue and cash flows, earning superior returns on invested capital, and increasing intrinsic value (or what investors think they are worth). The harder part is forecasting whether they can keep it going. So, how do you know? These companies leave clues—about their competitive advantages, their culture, and their adaptability—that reveal their ability to compound over time. This is where experience and judgment can pay dividends. We often create what we call our “Dream Team,” a shortlist that narrows our broad universe to a select group of companies for potential investment.

The other challenge is valuation. Other investors are looking for compounders too, which means the company’s valuations are often too high. This is where the value part of the process remains important. Being able to balance the two is necessary for success. Just because something is high quality doesn’t mean we want to overpay for it. It’s important to remember that even the strongest company still stubs its toe from time to time. Each of those tech giants I mentioned above has witnessed massive drawdowns in the past—some approaching 90%, creating opportunities for long-term investors, including me and my colleagues at Burgundy. As for the aforementioned Dream Team, we may initiate a position in one of those companies once its valuation becomes more compelling.

Finding that rare combination of a quality compounder trading at an attractive price can lead to what the late great Charlie Munger called a “Lollapalooza.” When multiple factors come together—in this case, quality, value, and compounding—an extremely positive outcome can emerge. Discernment and patience can lead to superior investment outcomes.

No Country for Old Men

Change is a central preoccupation of McCarthy’s novel, with some of the older characters wrestling with an inability to combat the chaotic realities of the modern age. They resist the evolving world, unable to adapt. Change is an unstoppable force, but if you’re open to exploring the opportunities of your surroundings, you can adapt and succeed. At Burgundy, we believe in staying curious. While it’s important to remain mindful of the elder sages, you must also learn from the younger generation. Growth is key—both personally and when it comes to the performance of our companies. When the old “cheap” playbook began breaking down, it was clear the game had changed. Before, you could sometimes get away with buying what looked cheap on paper and still come out okay. But in 2007 and beyond, that wasn’t the case anymore—for me or anyone else. The real margin of safety came from quality—companies that could take a hit, adapt, and keep on compounding. Today, while the enduring strength of a quality business may be more important than ever, the price still matters. Paying too much can still erase the benefits of even the best business.

Even Graham, the father of value investing himself, eventually caught the quality/value bug. His investment in GEICO wasn’t just about a low multiple. It was about a high-quality business with a durable edge, bought at a sensible price. And his most famous student, Warren Buffett, took that lesson even further. In his middle age, he made a similar shift, turning to higher-quality compounders. Remarkably, 99% of Buffett’s vast net worth has been accumulated since he turned 50. That is the power of compounding. Buffett’s example also serves as a reminder that when the rules of the game change midway through, you can (and probably should) adjust.

Inspiration can come from anywhere. What matters is being ready to receive the message. For me, McCarthy’s hitman was the unlikely messenger, and the lesson to adapt only deepened over the years. I believe long-term success comes where quality and value meet and where compounding can do its quiet work.

References & Disclaimer

- Martin Sosnoff, “If it Ain’t Controversial, Don’t Buy It,” Forbes, 1997.

- Rick Friedman, Catherine LeGraw and John Thorndike, “Beyond the Factor: GMO’s Approach to Value Investing”, GMO White Paper. 2024.

- Steve Jobs, commencement address at Stanford University, June 12, 2005.

This post is presented for illustrative and discussion purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment advice and does not consider unique objectives, constraints or financial needs. Under no circumstances does this post suggest that you should time the market in any way or make investment decisions based on the content. Select securities may be used as examples to illustrate Burgundy’s investment philosophy. Burgundy funds or portfolios may or may not hold such securities for the whole demonstrated period. Investors are advised that their investments are not guaranteed, their values change frequently and past performance may not be repeated. This post is not intended as an offer to invest in any investment strategy presented by Burgundy. The information contained in this post is the opinion of Burgundy Asset Management and/or its employees as of the date of the post and is subject to change without notice. Please refer to the Legal section of this website for additional information.