In recent months, the financial media has been preoccupied with debt. We understand the attention. A little over a decade ago, high levels of American household debt were a catalyst of the Global Financial Crisis. Debt peaked at 116% of personal disposable income at the end of 2007, right before the economy tumbled into a recession in the first quarter of 2008. Since then, U.S. households have done an admirable job of getting their balance sheets in order; household debt is now approximately 85% of U.S. personal disposable income.1

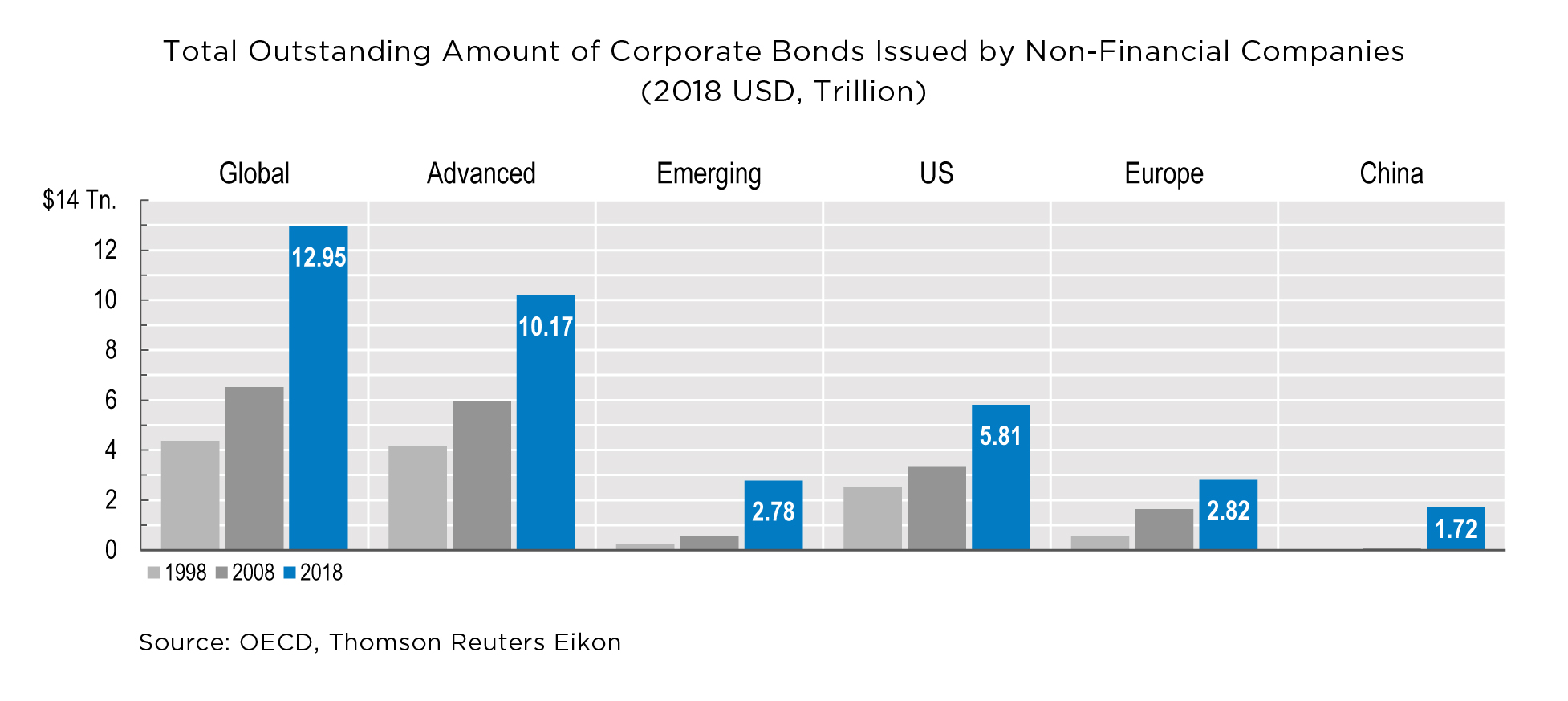

While U.S. households have been reducing debt, businesses have been doing just the opposite by issuing corporate bonds. According to a recent study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), total outstanding corporate bonds of non-financial U.S. companies is at a record high of US$5.8 trillion (compared to roughly US$2.5 trillion in 2008) and, globally, non-financial corporate debt has grown to US$13 trillion!2 Corporate debt has moved ahead of household debt as an area of concern.

In many ways, the increase in corporate debt is understandable. Short-term interest rates3 decreased from 5.25% in 2007 to a low of 0%–0.25% in late 2008 before starting to creep upwards more recently. With the cost so low, it is not unreasonable for management teams to use debt financing to grow their businesses. In fact, although debt levels have grown rapidly, the average company’s ability to make interest payments has improved. In the United States, corporate interest expense as a percentage of revenue has decreased from 14.8% in 2008 to 12.5% at the end of 2017.4

Recently, however, companies have been raising debt for non-productive reasons, such as share buybacks and dividend increases. This suggests that, in some cases, management teams are using cheap debt as a tool to boost shareholder returns rather than invest in their business.

Investors have also played a key role in this growing debt trend. Government bond yields are at or near all-time lows, and investors seeking higher yields are moving to corporate bonds. The resulting strong demand has allowed companies to issue debt with fewer protections for investors. These provisions (“covenants” in bond parlance) built into contracts are meant to protect bondholder rights. They range from limiting the amount of future borrowing, to specifying conditions necessary for dividend payments. As demand for yield has outpaced supply, companies have been able to issue debt with few or no covenants, meaning that bondholders are less protected on average than in the past. Further, lower-quality debt is being issued now more than ever before. The lowest-rated Investment Grade bonds (BBB) represent approximately 54% of investment grade issuance today, compared to approximately 39% during the prior cycle.2

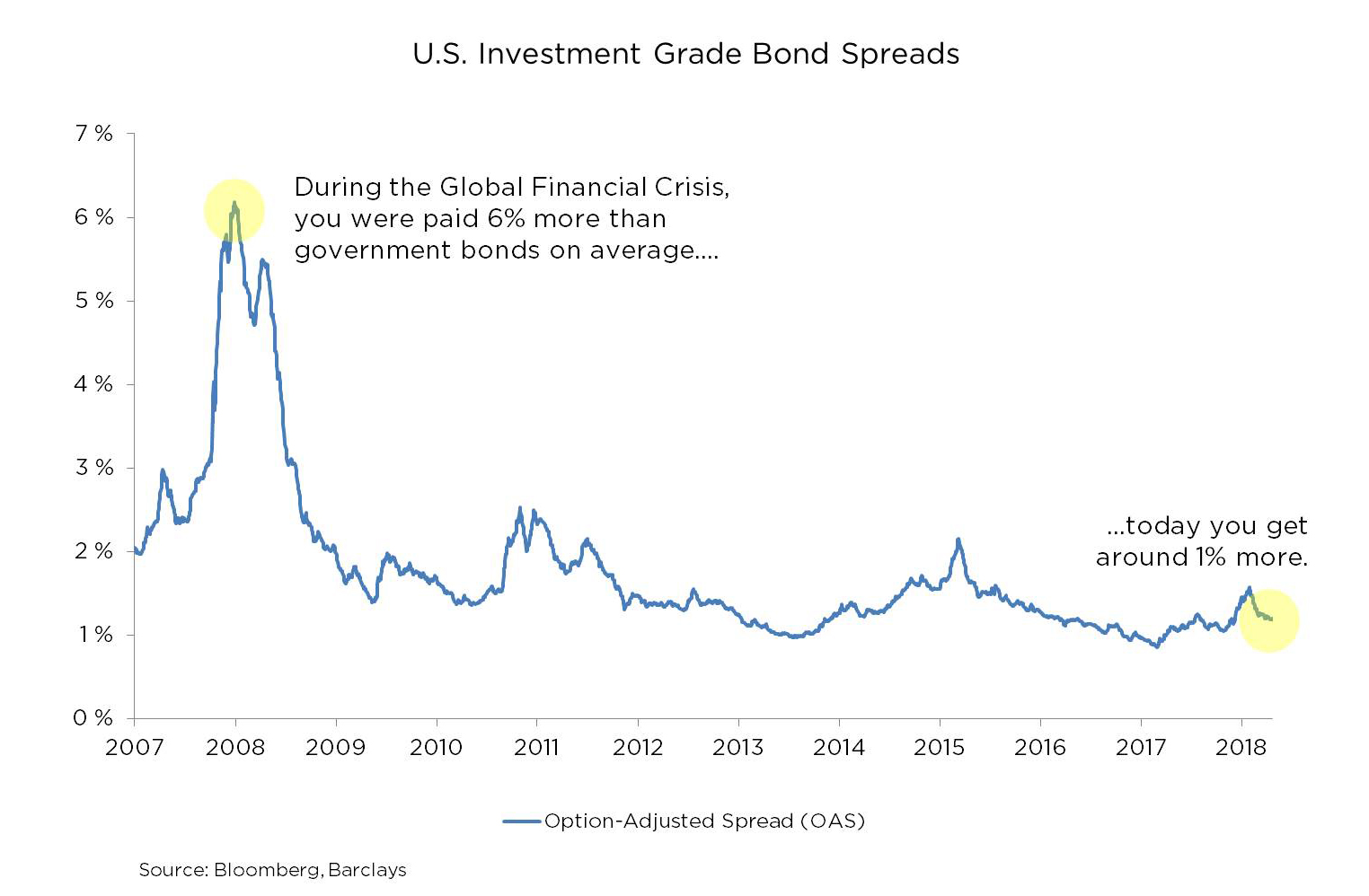

The insatiable thirst for yield has led investors to accept fewer protections and lower quality while getting paid less to take on this risk — a trade-off we do not like to accept. As seen below, the additional return an investor receives over a government bond to compensate for increased risk (known as the corporate bond spread) has steadily declined since the Global Financial Crisis.

The global corporate debt market may be US$13 trillion and rising, but the composition of the market has deteriorated. As such, the number of bonds we would consider including in our portfolios has not risen commensurately

Having few quality opportunities to choose from does not change our approach. We continue to focus on investing in the bonds of businesses that have strong fundamentals, appropriate levels of debt and are run by capable management teams. We ensure these companies are able to service their debt throughout an economic cycle, meaning we are cautious about owning the bonds of companies in cyclical industries where credit quality can turn quickly. We believe this approach minimizes the risk of permanent loss of capital by avoiding companies that have a risk of bankruptcy or are likely to be downgraded by one of the rating agencies. While we recognize and appreciate the concerns about the trends in corporate debt, we take comfort in our selective approach. We feel this strategy will deliver a more attractive risk-return profile for our clients over the long haul.

1. https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/interactives/householdcredit/ data/pdf/HHDC_2018Q4.pdf https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DSPI

2. Corporate Bond Markets in a Time of Unconventional Monetary Policy. https://www.oecd.org/corporate/Corporate-Bond-Markets-in-a-Time-of-Unconventional-Monetary-Policy.pdf

3. As measured by the U.S. Federal Reserve’s Overnight Lending Rate

4. WorldBank https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/GC.XPN.INTP.RV.ZS

Other Source:

This post is presented for illustrative and discussion purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment advice and does not consider unique objectives, constraints or financial needs. Under no circumstances does this post suggest that you should time the market in any way or make investment decisions based on the content. Select securities may be used as examples to illustrate Burgundy’s investment philosophy. Burgundy funds or portfolios may or may not hold such securities for the whole demonstrated period. Investors are advised that their investments are not guaranteed, their values change frequently and past performance may not be repeated. This post is not intended as an offer to invest in any investment strategy presented by Burgundy. The information contained in this post is the opinion of Burgundy Asset Management and/or its employees as of the date of the post and is subject to change without notice. Please refer to the Legal section of this website for additional information.