Richard Rooney, then President and CIO of Burgundy Asset Management, delivered the following presentation in Halifax at the International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans (IFEBP) Canadian Investment Institute Conference on August 13, 2012.

This speech was delivered over a decade ago, yet its message is just as relevant today. It explores the challenges of maintaining integrity, discipline, and long-term thinking amid growth and change – values that continue to guide our decisions. While our ownership structure is set to change by end of calendar year 2025, our core beliefs remain unchanged. This piece serves as a reminder of what has made Burgundy successful to date, and what we are committed to carrying forward.

The job we do as Trustees is one of the hardest I can think of. I say we, because I have served as trustee on several pension and endowment funds. Successful committees have to know something about the capital markets (at least enough to be afraid of them); they have to be able to assess investment managers, which is an art in itself; and they have to have good internal dynamics, balancing diversity of backgrounds and opinions with the ability to work together harmoniously and support the group’s decisions. I have served on about six of these committees, and most of them fell short in at least one of these areas. But that is a topic for another day.

Let’s focus on money management. I’ve spent almost 28 years in the business (for the consultants in the crowd that’s 111 quarters). I have worked in the investment department of a big financial institution (Sun Life Financial), at an index-oriented investment counsellor (AMI Partners), and for almost 18 years I have been at Burgundy Asset Management, where we pretty well started from scratch. About a third of Burgundy’s business is pension funds. We manage a number of different mandates for pension clients, including Canadian equity, balanced, EAFE/international, U.S. and Canadian small-cap, and global mandates in Canada, the U.S. and the U.K.

Identifying the Enemies of Value Added

First of all, let’s define our terms. My definition of value added is:

Making more money than an available low-cost indexing strategy, over a reasonable time frame, after all costs including management fees.

Enemies of value added for investment managers include size, benchmark orientation and lack of downside protection, among others. We’ll deal with all those issues at length, but in my opinion, they are only symptoms of a much more dangerous disease and one that very few investment managers survive: their own success. I hope to show you that by their very success as businesses, money managers usually plant the seeds for future shortcomings as investors. This occurs even though, ultimately, it is as investors that you are going to judge them. I hope to be able to give you some pointers on how to spot a manager who is on his way to negative value added.

ENEMY #1: SIZE

Let’s start with the negative relationship between size and the ability to add value. This one doesn’t apply to all asset classes. In some cases, being bigger can mean being better, because there are economies of scale, as there are perhaps in the bond business. In a lot of really large markets, such as U.S. equities, you have to get really huge before the problems of size start to arise. But there is one vital asset class where attracting a lot of assets can mean the end of value added for clients: Canadian equities. Let me show you a simple exercise to illustrate the point.

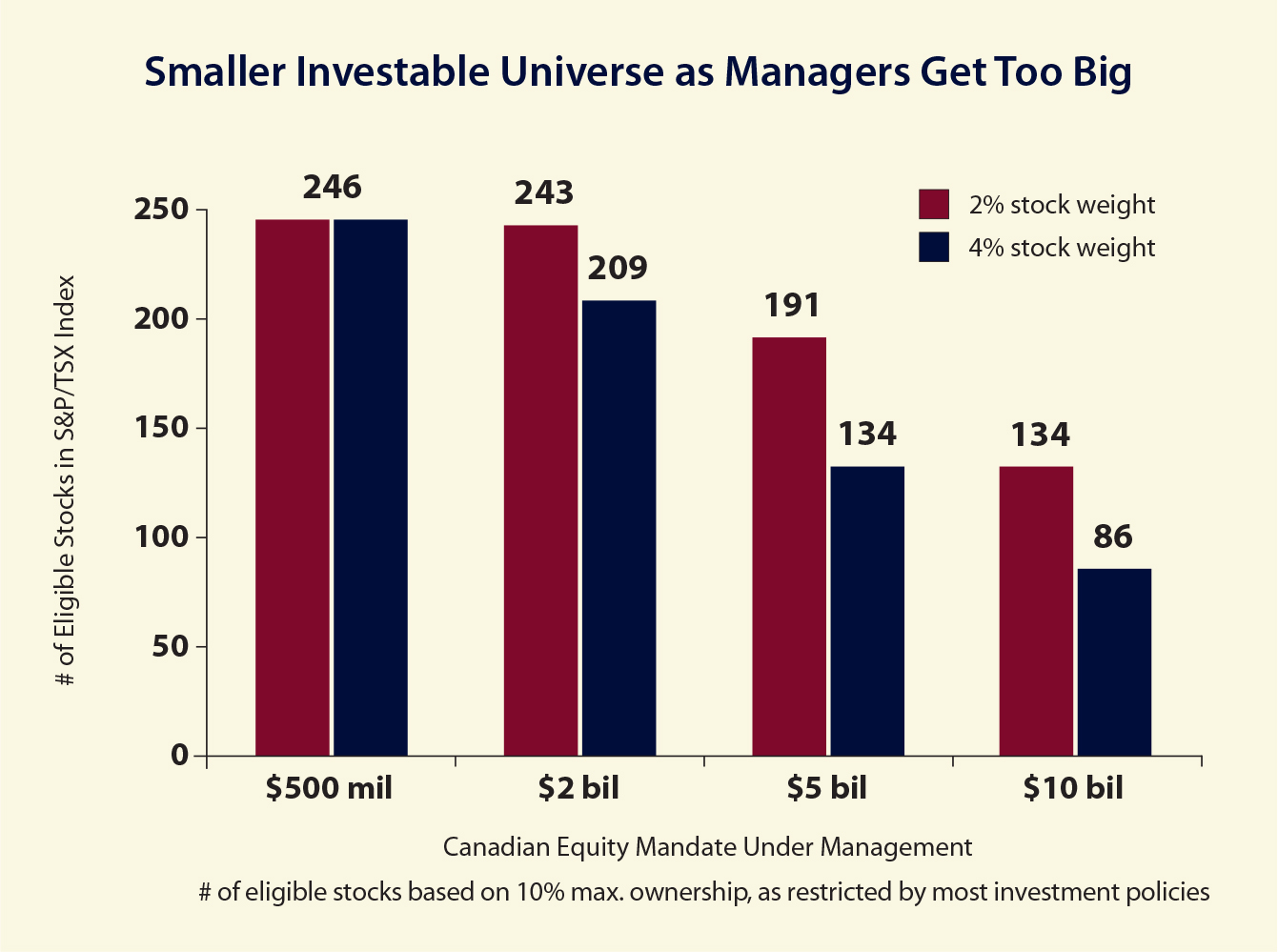

Let’s say you have four Canadian equity managers. They operate under these strict rules: first, they can’t own more than 10% of the stock of any company they invest in; second, they must own equally weighted portfolios of 50 stocks (2%) or 25 stocks (4%).

The manager with $500 million under management can own anything he wants from the 246 stocks in the S&P/TSX composite index under these rules. But for the managers with $2 billion and $5 billion, things start to get more restrictive. The manager with $5 billion has a lot of stocks he cannot own – 55 stocks in his 50-stock portfolio and 112 stocks in his 25-stock portfolio, to be exact. And, Mr. $10 Billion is really in trouble – he has access to only about half of the stocks in the index if he owns 50 names, and a third of them if he owns 25. We can be sure that for any companies toward the lower end of the capitalization range, he will be butting up against that 10% ownership barrier. The largest manager will have to own the largest companies available because those are the only ones he can get enough of. If he tries to own smaller companies he will end up owning a high percentage of their stock, and if anything goes wrong, he will not be able to exit his position. If things go really wrong, he will have to ride it all the way down. The $500-million manager, by contrast, will not amount to a very high percentage of the ownership or trading of any position he owns, and can enter and exit positions much more quickly and cleanly.

Investment managers usually make their reputations when they have fairly limited assets under management and lots of flexibility. Great returns are usually the result of buying something that is overlooked and undervalued in the market – and that is usually not the big, heavily traded, highly researched companies that the biggest manager has to own. Most investment managers will produce great returns from small- and mid-cap investing and as they grow they will migrate their funds to large caps. So if you are a really smart client and hire the $500-million manager, and he goes on a multi-year tear raising assets, you might find yourself after seven or eight years with the $10-billion manager after all.

The only way a manager can stop this process of limiting his own opportunities through growth is to close funds. You can see that if you close your fund, say, at the $2-billion level, you preserve a lot of flexibility for your clients even if you have concentrated portfolios. You would be using the best rule of thumb I can think of for closing funds – when your next client is not going to get the same product as your first client in your product.

Closing funds is very painful and difficult. You are usually doing it just when you are starting to get traction in the market and consultants are finally up to speed on your product. If you do it too suddenly and before you have another product ready, you can really tick off a lot of people. I speak from experience here.

Subscribe to Views & Insights

The important thing, though, is truth in advertising. If at the end of 10 years our $10-billion manager is showing Canadian equity numbers that were largely generated when he was managing much smaller amounts of money, then that is misleading. He will not be able to replicate those returns. It is far better to launch a new product where you openly proclaim that you will be selecting stocks from the smaller universe of large-cap companies. That way, everybody knows where you stand. You can still add value in the replacement product, just not as much as in the original. And, of course, at some point you will have to close the replacement product too.

What I am talking about here really is the difference between being an asset gatherer and an asset manager. The asset gatherer is just interested in getting big with the attendant profitability that brings. And, make no mistake, investment management is probably the most profitable legal business in the world. Every new client has an almost 100% profit margin. That is why most investment managers are run for the next client in the door rather than the ones they already have. That is why it’s so difficult to shake the growth habit once you’re hooked. Every new client helps make you rich, and remember: “Who wants to be a millionaire?” is a rhetorical question on Bay Street.

We’ll return to this point from a different angle later, but let’s continue on to the second enemy of value added we identified: index or benchmark orientation.

ENEMY #2: BENCHMARK ORIENTATION (CLOSET INDEXING)

We are all benchmark-oriented to some extent in this business. The first thing you probably look at in the quarterly report is how the manager did against his benchmark, though something tells me more and more of you are also looking to see if he made any money. There is nothing wrong with having a benchmark; it gives you some idea of how the manager is doing against the investments available to him.

The problems arise when the manager looks too much like the benchmark. And, the bigger he is in Canadian equities, the more his portfolios are going to resemble the benchmark. This is called closet indexing and it just means looking as much like the index as you can while pretending to manage money. It’s really the weights in the index calling the shots, not the investment manager.

How can you tell if your manager is closet indexing? Ask him to provide you with his active share.

Active share is a simple calculation that tells you how much the manager has in common with the index. Academic literature shows that managers with high active share add more value than managers with low active share. An active share of:

- 0 would be a perfect index fund

- 50 – 70 means the manager has reasonably large differences from the index

- 70 – 90 is very high and means the manager is actively exploiting opportunities that the index weights do not reflect

- 100 means the manager owns nothing in common with the index

You don’t want to pay much for closet indexing. If you are paying more than an index fee for a manager who will literally be unable to add value, you are getting ripped off. But it’s not just a matter of paying too much for something that is available cheaper. Blindly following the index is a dangerous strategy that can cost you a lot of money.

Capitalization-weighted indexes such as the S&P/ TSX weight stocks according to the number of shares multiplied by the current price. The higher the price of a stock, the greater its weight in the index will be. In normal times, that shouldn’t be a problem, but sometimes the market gets itself into a bubble – either on a sector or an individual stock – and things can get very dicey. If you look back over the past few years in the market, owning things just because they were big was a very dangerous strategy. Here are some of the more prominent torpedoes:

- Nortel: from $398 billion (2000 peak) to bankruptcy in 2007

- Research In Motion (RIM): from $60 billion (2008 peak) to less than $5 billion in four years

- Sino-Forest: from $6 billion (2011 peak) to bankruptcy

- Bre-X: from $6 billion (1996 peak) to bankruptcy

Investment managers shouldn’t own things because they are in the benchmark; they should own them because they have researched them thoroughly and believe the investments will give good returns to clients. A couple of these big index weights were outright scams; any manager who owned Bre-X and Sino-Forest has a lot of explaining to do.

The Canadian market is also troubling as a benchmark because it has become so narrow and shallow. When I started in the business, we had four public Canadian breweries, three distillers, two tobacco companies, five steel companies and the world’s largest mining companies (Inco, Alcan, Falconbridge and Noranda). They’re all gone, taken over by foreign companies. What’s left is not terribly appetizing, to be honest. Three industry groups account for more than three-quarters of the index – energy, materials and financial services. It’s an undiversified bet on a certain kind of global growth story. So you have another reason not to want a closet indexer as a manager – they are imitating a pretty poor benchmark.

ENEMY #3: LACK OF DOWNSIDE PROTECTION

It may seem odd, but investment managers, especially those who closet index, just forget that losing money is a bad thing, period.

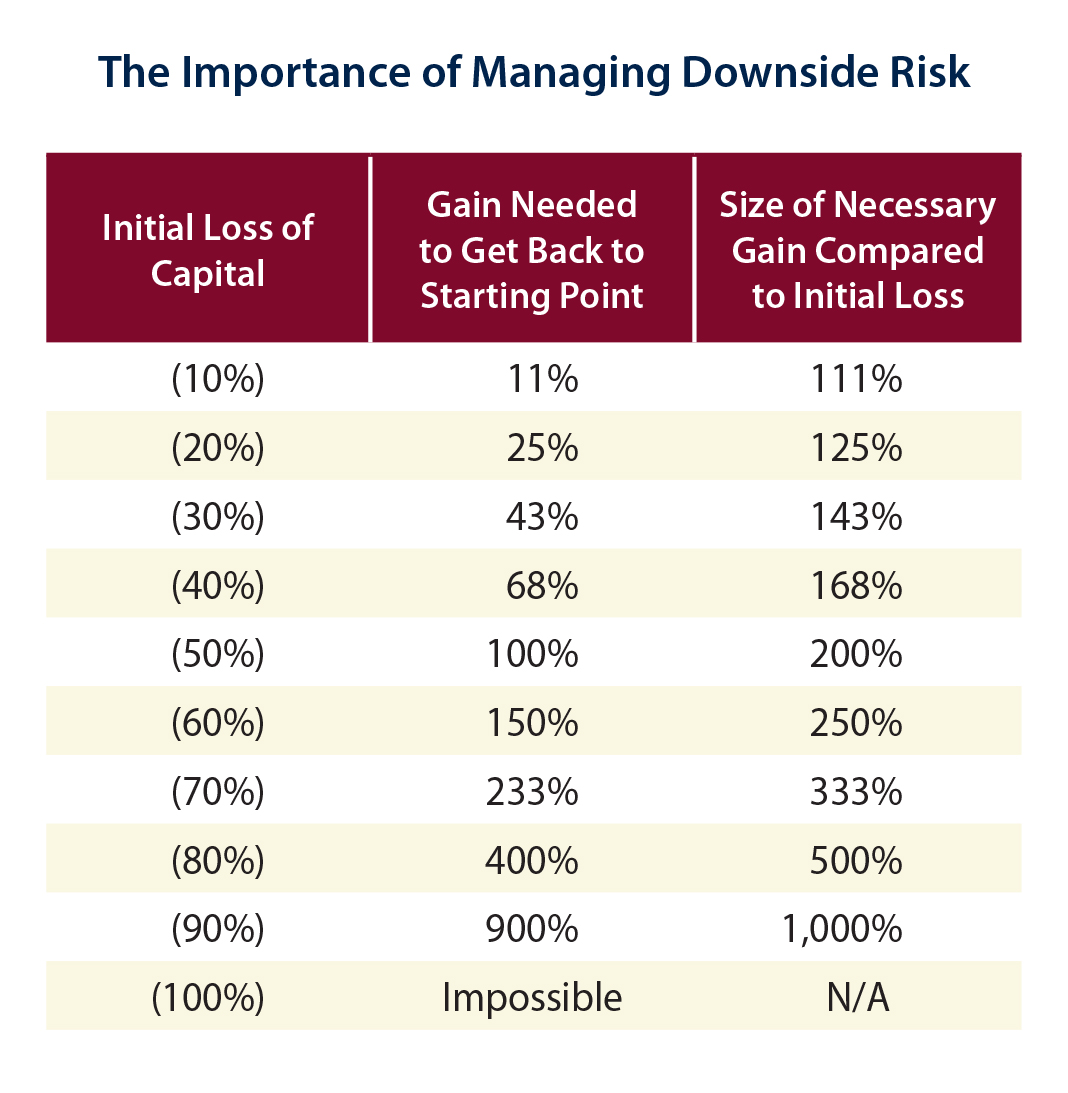

Here is a table that illustrates how destructive losses are:

If you lose 20% of your money, you need to make 25% to get back to even. If you lose 50% of your money, you need to double your money to get even. If you lose 75% of your money, you have to quadruple your money just to get back to your starting point. This is just math, but it shows how tough the investment job becomes if you have large drops in asset values. That is why 2008 was such a watershed – investors are all still trying to recover from the losses of that year.

There is a field of study called behavioural finance. It studies the reactions of real people to financial outcomes. The conclusions of those studies are consistent – people always find losses to be about three times as painful as they find gains to be pleasurable. Those of you who have served for a long time on investment committees will probably confirm this – when you see a 20% gain you feel pretty good, but when you see a 20% loss you feel like you’ve been kicked in the head. It’s not just you – it seems to be how we’re hard-wired psychologically.

You’d think that investment managers, who are usually good at math and who generally know about these behavioural issues, would therefore spend a lot of time thinking about the downside of their investments. But that is not the case. They are often so focused on the benchmark that beating it becomes their only concern. Who here hasn’t been frustrated when a manager comes in for a review and looks as pleased as punch that he is only down 10.5% when the market is down 11%? From a trustee’s perspective he’s thinking the wrong way – but as far as he’s concerned he’s lost just enough money not to get fired.

I mentioned that I felt all of these enemies of value added were really just symptoms of a more serious disease – success. I wonder how many of you have ever seriously thought about what is going on in the organizations that manage your money.

At its base, the problem is that there are two kinds of success an investment manager can achieve. One is investment success, which involves producing competitive returns for clients over long periods of time, and adding value to client benchmarks. That is what I call professional success. If it is achieved, it is very good for the client as well as the investment manager. The other kind of success is business success. Business success involves maintaining and growing assets under management, and generating profits for the owners. These two kinds of success, professional and business, are always in competition with each other in an investment management firm. As these firms grow and prosper, almost always as a result of their professional success, business concerns and issues come to predominate and ultimately take over the firm. The waning of professional concerns, the reduction of investment focus and its replacement by focus on appearances rather than substance and results are what kills investment managers.

Let me illustrate.

The Investment Manager Life Cycle

I would like to quickly run through the life cycle of a money management firm from birth to death and the challenges that arise at each stage. It is quite predictable and leads to the same pathologies over and over again. I hope to show you how a perfectly logical and sensible series of responses to the issues of growth and management of the business will almost inevitably lead to a situation where the manager is unable to add value and may actually be endangering the financial health of his clients.

BIRTH

A new investment management firm is usually started by one or two investment people who leave a large organization to set up shop. They are convinced that if they can just escape the constraints of the large organization, they will be able to perform well and attract clients. They will start with a determination to focus completely on investments, and probably with a desire to keep it simple, offering one or two focused products. In Canada, usually that product will be Canadian equities. What are the characteristics of this new firm?

They have one objective: survival. And, they have only one means of survival: producing good returns. A startup firm has an energy and focus about it that makes being there an unforgettable experience. You are in a race against time – you have to produce a good enough track record to attract clients, and do it before you go bankrupt because you have probably invested your life’s savings in the firm. There are no distractions from the goal of producing returns. As you can imagine, at this level, client interests and investment manager interests are perfectly aligned. Clients who have the guts to hire you are rewarded with total investment focus and personal service too. I still make a point of servicing Burgundy’s early clients, because you “dance with who brung you.”

So am I recommending that you all go out and hire startup investment managers to run your pension funds? Of course not. These managers will have a high rate of failure because not everyone is able to manage money for competitive returns. It really all depends on the people involved – if they are experienced and disciplined, they will survive and prosper and so will their clients. So if you see someone with a significant amount of experience (say 7 – 10 years) leaving a big organization to set up his own shop, you might consider giving them a meeting, if only to contrast them with your current manager.

THRIVING CHILDHOOD

Let’s assume our new firm beats the odds and produces numbers that start to attract a client base and early adopter consultants. This can happen pretty fast – in my firm’s case it took about three or four years (though it didn’t feel that fast at the time). If you stay in style for a couple of years, you will start to attract a lot of clients. The young firm will start to hire client-facing people to handle the relationships. The firm will start to hire administrative people to handle compliance, contract and transaction matters. The firm will have to hire more and more managers to manage the people in these various departments. If the investment people are trying to manage the firm, as they often do in this early stage, they will find it more and more distracting and difficult to deal with the people issues. Remember, investment people are usually analytic personalities. They love numbers and concepts. They don’t tend to be crazy about people, and that can make them very poor people managers.

You can see even at this early stage how the demands of the business are starting to encroach on the demands of the profession. New clients mean more revenue, but also more complexity, and you have to build headcount to deal with the complexity.

TROUBLED ADOLESCENCE

And then, inevitably, the firm experiences its first setback. Performance falls off, at least partly because the investment people are now doing something they are ill-prepared for, which is managing people. Usually it will also have to do with the firm’s style falling out of favour. Tensions between the management of the business and management of the portfolios become acute at this stage.

Lots of firms fall apart here, with departures, layoffs and loss of professional reputation. In some cases, the managers may sell their business to a big financial institution and just exit. Let’s assume the firm holds together and decides to reinvest and reorganize. A review of their business will show that they are far too dependent on one asset class (usually Canadian equities). So they will begin to build or acquire expertise in other asset classes, perhaps fixed income or foreign equities. They will bring in high-powered management talent to ensure that the firm’s people are mobilized correctly. What they will probably not do is close their main fund, although this would be a good time to do that.

PRIME OF LIFE

If the reorganization works, the company comes into its own. New investment people are hired and assets can build to a very great extent. There will be a renewed sense of permanence about the firm, and they will become a safe bet for pension investors. Presentations will be slick, relations with consultants and clients will generally be cordial, and resources to support those relationships will be plentiful and effective. This period can last for decades and business success will be tremendous. The firm can continue to add value, though its contribution will be falling gradually over time as assets grow. And then, at some point, a fresh set of problems will arise.

THE LONG GOODBYE

I call the last period the long goodbye. The founders of the firm have to start thinking about an exit strategy. The investment managers who have generated the good returns are aging, and increasingly at risk of health problems, disability, divorce or any of the other things that can alter the course of a life. The next generation of investors may not be given the opportunity for the same degree of risk-taking and initiative that the originals were given. And, of course, that is because they have a very large business to protect.

At this stage, business concerns are paramount. People are less concerned with excellence on the investment side. They simply want to do well enough not to get fired. That old chestnut about being first quartile in the long term if you can just stay above the median for a few years will start to be used. Who ever heard of excellence through mediocrity in any other walk of life?

Due to the (in some ways quite justifiable) obsession of consultants with investment manager turnover, there will be a tendency to pretend that investment management is now being done by groups or committees so the original managers can sneak out the back door without scaring too many people. They will misleadingly call these groups “teams.” Sometimes you will see groups of 20 or 30 people that are allegedly managing the funds. Now, I have dealt with investment people my whole life and I can tell you that if you give them a place to hide, they will hide. And, in a group that big, everybody is hiding. Nobody takes responsibility, everybody is risk averse, and ultimately everybody looks to the benchmarks for their lead in managing the portfolios. How overweighted or underweighted you are becomes the test, rather than the characteristics of the company as an investment. You will get negative selection as the investment people who want to make a difference get frustrated and leave to form their own firms, and the timid and bureaucratically adept will stay.

The most dangerous thing about this situation is that the manager is systematically depleting the very thing that is most vital to his clients’ long-term financial health: the ability to assess investment risk. A committee member who owns something because it is a large part of the index is not assessing the risk of the investment – he is protecting his business from the risk of being different from the index. And, ultimately that decision to hold Nortel or Sino-Forest will lead to severe underperformance. And, the manager by that time will no longer possess the skills to make up those losses to the clients.

This is the portrait of an investment manager at the end of its rope. If you looked at the income statement, you would say it is a phenomenally successful business. But then look further.

Characteristics of a Messed-Up Manager

The company probably has a huge portfolio of Canadian equities that looks suspiciously like the index. Investment decision-making is unclear, with responsibilities split up among so many people that nobody is really in charge. The so-called team always looks to the index and they spend a lot of time on portfolio attribution rather than the companies you are investing in when they come to talk to you. They don’t have a handle on the downside risks in the portfolios, though they can probably show you a lot of statistical stuff that they will call “risk controls.”

Sound familiar? This manager is too large, too index-oriented and has lost the ability to assess downside risk. All three of our enemies of value added, all arrived at due to business success and logical business decisions, and all very predictable.

So what am I suggesting we do about these issues? Every two or three years, I believe you should devote a session with your investment manager to how his firm is doing as a business. Here are some questions I would ask on our three main issues:

QUESTION #1: IS YOUR MANAGER TOO BIG?

The size issue is pretty easy to address. For Canadian equities or small caps, ask the manager how much they have under management in that asset class, and how that has changed over the past three and five years. Ask if they ever close funds, and if they have any intention of closing the fund in which you are invested. If the growth rate of the assets under management has been rapid, you can assume there are management challenges arising in the business. Ask about growth in headcount, and how they are managing the growth. You should be able to get a handle on whether they are asset managers or asset gatherers from this conversation.

QUESTION #2: IS YOUR MANAGER A CLOSET INDEXER?

The benchmark orientation issue is also easy to figure out. I mentioned before that you should get your manager to calculate his active share. If the number is very low, like 30%, you had better be getting a very low fee. In fact, you should examine the possibility of indexing the portfolio just to see how low the fee should be. The active share calculation will tell you how index-oriented your manager is. Your committee will decide on what its comfort level is, and you can go from there.

QUESTION #3: IS YOUR MANAGER PROTECTING DOWNSIDE RISK?

Downside protection is less easy to estimate. There is something called a Sortino ratio that measures the extent to which a manager is likely to perform badly on the downside, and your consultant may be able to use that. But probably the best test of downside protection is simply the manager’s track record in down months, quarters and years. You can probably get a feel for this from their presentations as well. Do they talk about the benchmark all the time, or do they talk about the businesses in which they have invested your money?

Ask who is in charge, who takes responsibility for the whole portfolio. Where does the buck stop? If you can’t get a clear answer on this one, the rot goes deep. If they show you a massive group of people with finely divided responsibilities and call it a team, you’re really in trouble. At that point the investment process is compromised and your downside may be unprotected.

Summary

My topic focused on three factors that can inhibit your investment manager from achieving value added: size, benchmark orientation and a lack of downside protection. I have also discussed the way investment managers develop over time and the difficulties they face in balancing professional and business success at each stage. The three inhibitors of value added are ultimately symptoms of an underlying disease – the business success of investment management organizations. Business success will often be to the detriment of professional success – and the client’s portfolio.

An investment organization that wishes to avoid these pitfalls must make painful choices that can lead to slower growth, which is never entirely popular in the investment management business. Closing mandates before they become too large, maintaining high active share and ensuring that responsibility for decision-making in the investment department remains rational and clear are all things that are very difficult, but essential for value added.

I do not believe that the problems I have outlined are inevitable or irreversible. They are, however, normal in the industry. It is a lot easier for money managers to get it wrong than to get it right. Your job, then, is to remain diligent in examining your investment manager. Hold sessions dedicated solely to an analysis of his business, rather than yours. Identify any of the trends that might lead to his being unable to add value. If you remain diligent, you should be left with a manager who strikes the balance between business and professional success, while continuing to add value in your portfolio.

This post is presented for illustrative and discussion purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment advice and does not consider unique objectives, constraints or financial needs. Under no circumstances does this post suggest that you should time the market in any way or make investment decisions based on the content. Select securities may be used as examples to illustrate Burgundy’s investment philosophy. Burgundy funds or portfolios may or may not hold such securities for the whole demonstrated period. Investors are advised that their investments are not guaranteed, their values change frequently and past performance may not be repeated. This post is not intended as an offer to invest in any investment strategy presented by Burgundy. The information contained in this post is the opinion of Burgundy Asset Management and/or its employees as of the date of the post and is subject to change without notice. Please refer to the Legal section of this website for additional information.