Long-term care planning makes for a difficult—yet essential—conversation.

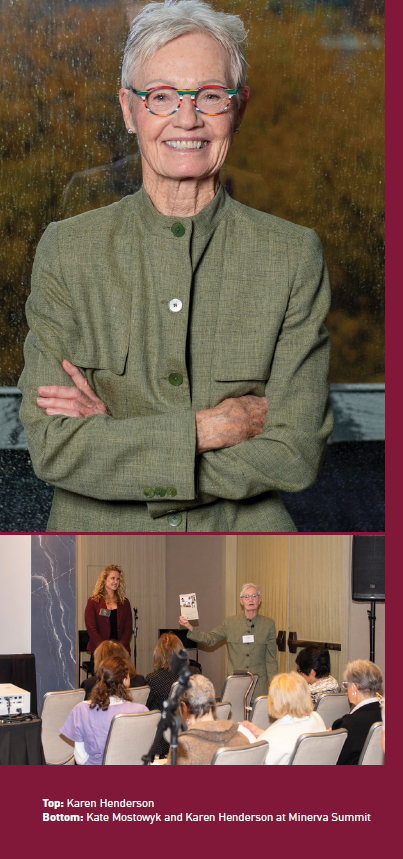

Nearly half of Canadians will require some form of long-term care after age 75, making it an issue that deserves our attention. During her workshop at last fall’s Minerva Summit, long-term-care expert Karen Henderson—founder of the Long Term Care Planning Network and a respected speaker, educator, and consultant with over 25 years of experience—provided insight into the planning process, from asking the right questions to finding the best resources. Kate Mostowyk, Vice President, Investment Counsellor for Burgundy’s Private Client Team, recaps Henderson’s must-know advice.

As we age, many of us tell ourselves we won’t need long-term care. What we’re really saying is that we don’t know enough about it or can’t imagine ourselves needing such support. The truth is, long-term care isn’t just about nursing homes—it’s about the entire journey we take through the healthcare system as we age and need more support. Ahead, we’ll explore the full spectrum of care options available to us, from aging at home to end-of-life care. We’ll look at the costs involved, what government support you can expect, and the critical factors that influence our care decisions.

The Long-Term Care Continuum

Long-term care encompasses the essential support services that help maintain our quality of life when dealing with chronic illness, disability, or cognitive impairments. This includes help with daily activities like bathing, eating, dressing, and moving around. While it doesn’t cure conditions, it helps us live as well as possible until the end of our days.

Our journey typically begins at home, where most of us want to stay. It’s familiar, it’s safe, and it’s where we feel most comfortable. However, the reality of aging at home often comes with a stark financial revelation: provincial governments provide limited subsidized care, forcing many to pay for private alternatives. Home-care costs range from $30 to $80 per hour, adding up to about $35,000 annually for just a few extra hours of private pay daily support. Full-time care can exceed $100,000 per year. When home care becomes insufficient, many consider retirement or assisted-living facilities. These privately owned establishments can offer a luxurious lifestyle with readily available access to support services. However, the initial monthly rent—ranging from $4,000 to over $12,000—typically includes minimal care. Additional care packages come at extra cost, and unlike some other health-care services, retirement homes typically receive no government subsidies. The entire cost comes from the resident’s own resources.

The next stage in the journey is longterm care, a nursing home, or memory care. While ownership varies between for-profit companies, non-profits, and municipalities, all must provide 24/7 care under provincial legislation. The financial structure here differs: the government covers food and care costs, while residents pay only for accommodation ($2,000 to $3,000+ monthly in 2024 depending on the province). However, accessing these facilities can be a significant challenge. Every province maintains a waiting list, with Ontario facing the most severe shortage of space—approximately 40,000 people currently await placement. Many could remain in their homes if sufficient provincially subsidized home care was available. Instead, they find themselves forced onto waiting lists for institutional care they’d prefer to avoid.

“The truth is, long-term care isn’t just about nursing homes—it’s about the entire journey we take through the health-care system as we age and need more support.”

The final stage is palliative or end-of-life care. At its best, this integrated approach provides comprehensive support for both the dying person and their family, managing pain and symptoms while providing emotional support. While many express a preference to die at home, the reality is that most deaths occur in hospitals. Of those who do manage to spend their final days at home, only about 15 percent have access to fully integrated palliative-care services, though these are typically covered by provincial funding.

Government Support and Limitations

Understanding government support for aging and health care can be confusing, but it’s crucial for planning purposes. The Canada Health Act mandates certain coverage, while other support varies significantly across provinces.

The foundation of our health-care system rests on the Canada Health Act, which requires provinces to subsidize medically necessary physician care, hospital care, and diagnostics. Beyond these basics, governments provide:

- Food and care costs in long-term care homes

- Limited home-care hours

- Some physiotherapy services

- Comprehensive long-term care for veterans through federal programs

- A new national dental-care program for those under 18 and over 65, though with strict criteria and limited participating dentists

- The emerging National PharmaCare program, currently covering diabetes and contraception drugs

What’s Partially Covered or Missing:

Long-term care itself falls outside the Canada Health Act, which explains several significant gaps in coverage:

- Retirement living receives almost no government support, with British Columbia being the only province offering limited aid for assisted living

- Prescription drug coverage varies by province, with each maintaining its own formulary of subsidized medications. Many expensive drugs remain uncovered

- Optometry services face continued provincial cutbacks

- Caregiver support is minimal; only Nova Scotia offers direct compensation for those who leave work to care for family members

- Home-care hours are limited, forcing many to pay privately for additional support

Critical Factors in Long-Term Care Planning

While most of us hope to age in our own homes and communities, successful planning requires honest assessment of whether our homes are truly suitable for aging. Two critical factors often force unexpected changes in our aging journey: falls and social isolation.

Falls, a leading cause of hospitalization and transition to long-term care, represent one of the most underestimated risks of aging at home. They happen in an instant, yet can permanently alter our lives. One in three people over 65 will experience a fall, though many keep it to themselves—a dangerous choice that prevents them from accessing vital fall-prevention programs. By age 90, falls become nearly universal, costing our health-care system over $15 million daily. Despite these sobering statistics, many dismiss the risk with thoughts like, “It won’t happen to me,” or “I’ll just pick myself up and keep going.”

Equally concerning is the impact of loneliness and social isolation. Research has shown that lonely seniors face a 59 percent higher risk of physical decline and a 64 percent increased risk of developing dementia. The evidence is clear: Social connection isn’t just about quality of life, it’s a fundamental health concern.

The time to start planning is now, before health issues arise. For families discussing parents’ care needs, consider the 40/70 rule: When children are around 40 and parents around 70, it’s time to start the conversation. While these discussions may take months or even years, it’s never too late to begin planning.

Several factors can indicate a future need for long-term care. Age is the most obvious, with women facing higher risk due to longer life expectancy. Other risk factors include existing disabilities, single status, lifestyle choices, current health conditions, family health history, and mobility issues. Even couples who currently support each other must consider that the surviving spouse may eventually need additional care.

When evaluating whether to remain in your home, ask yourself some crucial questions: Do you have adequate support systems in place? Can your home be adapted with a main-floor bedroom, bathroom, and laundry room to minimize stair use? Are you located near essential services, like transportation, medical care, and pharmacies? Can you maintain social connections? And, perhaps most importantly, can you afford the home care you’ll likely need?

Additional Considerations for Long-Term Care Planning

Additional Considerations for Long-Term Care Planning

While many people, particularly those in their 50s who are healthy and active, believe they can postpone planning for long-term care, two critical factors make early planning essential.

First is the rising prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease. Currently, over 700,000 Canadians live with some form of dementia, with more than 350 new diagnoses daily. Women represent 60 percent of cases, largely due to their longer life expectancy. While Alzheimer’s typically affects those over 65, early -onset cases can occur in people as young as their 30s. Though there’s no known cure, research published in The Lancet suggests that nearly half of all dementia cases could be prevented or delayed by addressing modifiable risk factors. These include hearing loss, social isolation, and various lifestyle factors. Simple interventions, from wearing hearing aids to maintaining social connections and pursuing lifelong education to build cognitive reserve, can significantly impact risk reduction.

The second consideration is end-of-life planning, including the possibility of medical assistance in dying (MAiD). Since its legalization in 2016, over 31,600 Canadians have accessed MAiD, with the average age being 76. Eligibility criteria include being seriously ill, suffering significantly, and making the decision voluntarily after receiving comprehensive information about treatment options, including palliative care. The most common conditions leading to MAiD requests are cancer, neurodegenerative diseases like ALS, and severe lung diseases. Recent changes in Quebec now allow advance requests for MAiD through power of attorney documentation, a significant development that may influence policies across Canada.

These complex considerations underscore why early planning is crucial. Working with health-care and legal professionals can help navigate these decisions, but the most important question remains personal: Can you afford the lifestyle that will make you happiest as you age? After all, maintaining quality of life throughout our final years is the ultimate goal of all this planning.

“The most important question remains personal: Can you afford the lifestyle that will make you happiest as you age?”

Taking Control of Your Future

While there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to long-term care planning, taking action now can help ensure a better future. Start by understanding how the continuum of care works in your province. Exercise, eat well—stay as healthy as possible to avoid hospitalizations, which pose particular risks for older adults.

Being proactive means more than just maintaining health. Keep your home safe, understand potential health challenges you may face, and, most importantly, communicate your wishes clearly to family, professional advisors, and medical teams. No one should have to guess what you want as you age. Organize your legal documents and important information in one accessible location, and don’t delay making decisions about future accommodation.

Resources are available to help you navigate this journey. The Alzheimer’s Society of Canada offers comprehensive information, including the LANDMARK Study (as written here) and brain health assessments. For understanding care options, particularly around dementia, the Advanced Directive for Dementia provides valuable educational guidance. Review the resources that are available through your provincial healthcare system and local hospitals.

Remember, the key to aging well isn’t just about having a plan—it’s about taking action while you still can. Start today, keep moving, and take control of your future care journey.

This post is presented for illustrative and discussion purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment advice and does not consider unique objectives, constraints or financial needs. Under no circumstances does this post suggest that you should time the market in any way or make investment decisions based on the content. Select securities may be used as examples to illustrate Burgundy’s investment philosophy. Burgundy funds or portfolios may or may not hold such securities for the whole demonstrated period. Investors are advised that their investments are not guaranteed, their values change frequently and past performance may not be repeated. This post is not intended as an offer to invest in any investment strategy presented by Burgundy. The information contained in this post is the opinion of Burgundy Asset Management and/or its employees as of the date of the post and is subject to change without notice. Please refer to the Legal section of this website for additional information.