Here’s What Happened

The stock market crash in early 2020 was unparalleled in history due to the pace of price declines, the speed and breadth of monetary and fiscal policy responses, and the immediate impact on businesses globally. In this article, we guide you through the news in the early days of the crisis, and take you behind the scenes of the market shaping events that ensued. While we are still in the midst of the novel coronavirus crisis, we have yet to see the full impact on the markets and on business. The time period we cover, January 1st through April 30th, was rife with extremes, many of which we have not witnessed before.

JANUARY 1–FEBRUARY 19

January began with China in the midst of grappling with an outbreak of pneumonia, cause unknown, in Wuhan City, Hubei Province. A novel coronavirus, later named COVID-19, was identified as the cause. On January 1st, Chinese authorities identified a Wuhan wet market (a market in which vendors often slaughter animals at customer point of sale) which they believed to be the source of the outbreak. The first death related to the coronavirus in China was reported on January 11th.1 By January 23rd, China had locked down Wuhan, a city of more than 11 million people.2

Isolated cases of COVID-19 began to emerge around the world by the end of January. First cases were reported in Japan, South Korea, and Thailand on January 20th, the United States (Washington State) on January 21st, Europe (Bordeaux and Paris) on January 24th, Canada (Toronto) on January 25th, and Italy (Rome) on January 31st.3 On January 30th, the World Health Organization (WHO), declared a global health emergency, only the sixth time it has done so since it was founded in 1948.4

By late January, businesses with operations in China were feeling the effects. Ferrari, the Maranello, Italy based luxury sports car maker, counts China as one of its biggest markets. A number of the company’s managers returned to Italy from China on January 21st bringing first-hand news of the virus outbreak. This promoted a call to action to build readiness for a similar outbreak in their own town in Italy, including travel restrictions, a procurement program of masks, gloves, antiseptic and implementation of physical distancing in its plants and offices.5 Global technology leader, Apple, temporarily closed its stores and corporate offices in China on February 1st.6 The same week, on February 4th, Canada Goose cut its fiscal 2020 revenue target citing sharp declines in its retail sales in China due to the coronavirus outbreak.7 A few weeks later, on February 17th, Apple reported that it would miss Q1 revenue targets due to weak consumer sales and production slowdowns in China.8

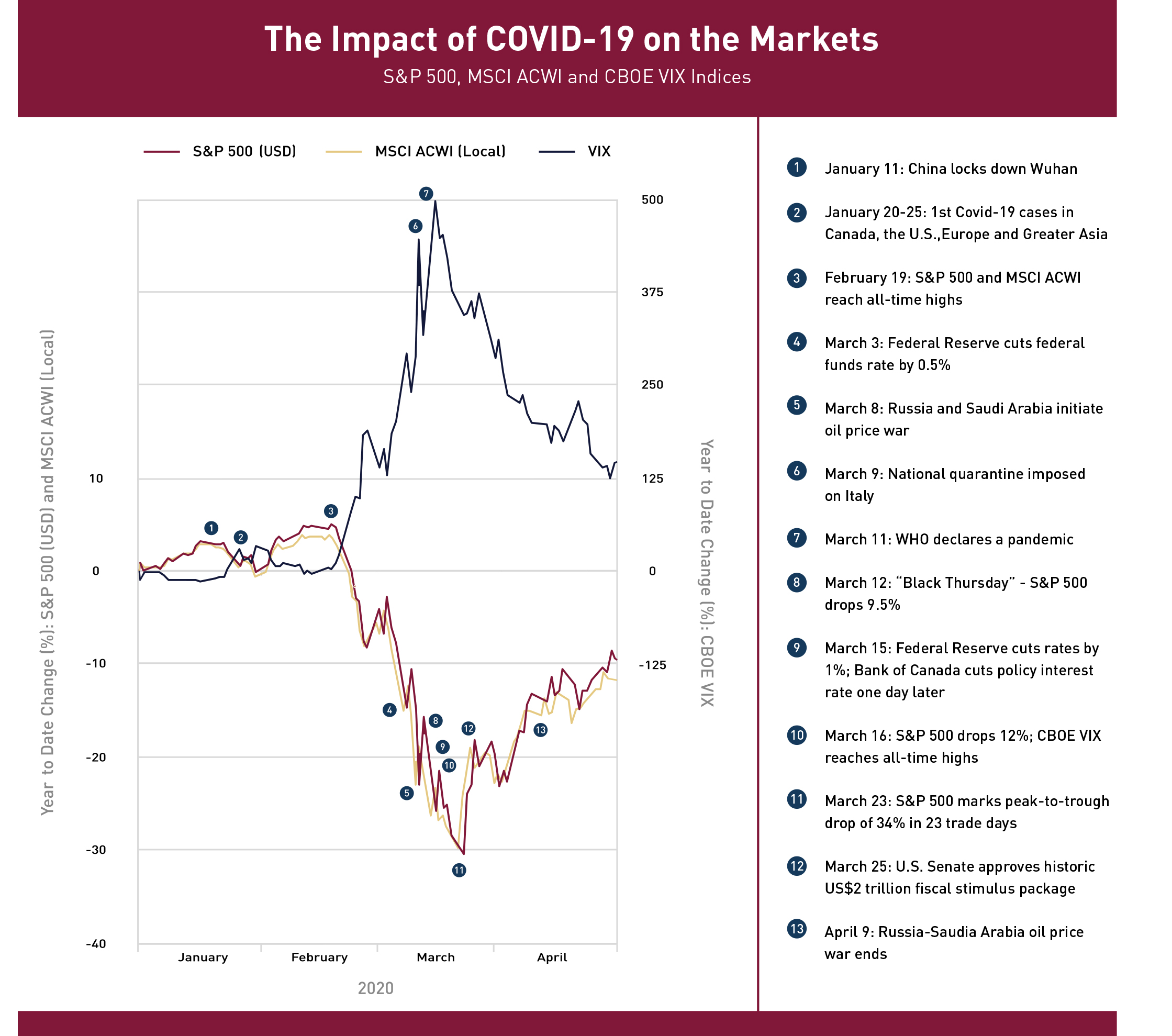

Outside of Asia, investors continued to drive markets higher, perhaps reflecting optimism that the challenges in China would temporarily affect supply chains and revenue generated in China, but little else. On February 19th, U.S. and global stock markets, as represented by the S&P 500 and the MSCI All Country World Index (ACWI), reached all-time highs. Volatility in the markets, as measured by the Chicago Board of Exchange VIX index*, was low (14.38). It was interesting that gold also rose, to $1,614.40 (US) a troy ounce, very close to a seven-year high. A rally in gold is often a harbinger of negative news to come and, although no one knew it at the time, February 19th marked the peak of the bull market that began 11 years earlier in the depths of the Global Financial Crisis on March 9th, 2009.

FEBRUARY 20–MARCH 11

Sentiment toward stocks soured on February 20th and 21st as news about the spread of the novel coronavirus worsened. 9 Reports of significant economic disruption were mounting. The China Passenger Car Association (CPCA) reported that car sales during the first 16 days of the month had plunged to just 4,909 units, a 92% decline from the same period in 2019.10 The prevalence of stock buyers over sellers just one week prior evaporated. The week of February 24th to 28th recorded the largest one week stock market decline since the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2009. The S&P 500 and the MSCI ACWI were down approximately 11.5% and 10.5% on the week respectively.11 Declines from February 19th marked the fastest correction in market history from an all-time high, taking merely six trading days to enter into correction (>-10%) territory.12

In response, central banks in the U.S. and Canada enacted monetary policy stimulus. On March 3rd, the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury notes fell below 1%, a sign that money was flowing to “safe haven” investments. The U.S. Federal Reserve, under Jerome H. Powell’s leadership, cut the federal funds rate by half a percentage point to a range of 1.0 to 1.25%.13 Canada’s central bank governor, Stephen Poloz, followed one day later with an equivalent policy interest rate cut from 1.75% to 1.25%.14

In the midst of the coronavirus induced market correction, Russia and Saudi Arabia initiated an oil price war. On March 8th, Saudi Arabia announced it would increase its oil production from 9.7 million barrels per day to 12.3 million barrels per day, while Russia planned to increase its production by 300,000 barrels per day. The contemplation of excess supply precipitated large-scale oil price declines, beginning with 30% declines overnight, the largest single day drop since the Gulf War in 1991.15,16

On March 9th, the Italian Prime Minister imposed a national quarantine on Italy. 17 The same day, amidst fears of the challenges posed by COVID-19, investors were digesting the oil price crash and news that Apple’s February iPhone sales in China came in at just 497,000, 60% lower than in the same month a year earlier.18 The S&P 500 fell 7% in the first four minutes of trading, triggering the circuit breakers that halt trading on all U.S. stock markets for 15 minutes, a measure aimed at calming markets and preventing an intraday crash. By the end of the day, the S&P 500 was down 7.6%. At the time, this was the worst one-day drop since the 8.8% drop on December 1, 2008 during the Global Financial Crisis.19

On March 11th, the WHO declared the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic.20 On that day the Bank of England, noting difficult conditions ahead, lowered its official borrowing rate, the “base rate,” by half a percent to 0.25%.21

MARCH 12–MARCH 23

Fears of the widespread economic damage a pandemic could invoke drove investors back to the equity markets with sell orders that far exceeded bids. On March 12th, U.S. market circuit breakers were again triggered, but the selling pressure caused a drop of 9.5% in the S&P 500 by the end of the day.22 This day became marked as “Black Thursday” 2020. Volatility in the markets was at extraordinarily high levels with the VIX index, Wall Street’s “fear gauge,” reading 75.47. At 525% higher than VIX levels a month earlier, and the highest by a long shot since December of 2008, it was a clear indicator of fear dominating the markets.

It was not just stocks that tumbled. The credit markets (bonds) experienced price declines due to wide price gaps between buyers and sellers. High yield, also known as junk bonds, and emerging markets issuers were especially hard hit.23 Perhaps the most puzzling part of the March 12th selloff, was that gold bullion and U.S. Treasury bonds also declined in price. These assets would normally be considered safe havens when fear and uncertainty reign, and as such, investors’ “flight-to-safety” would typically result in gold and U.S. Treasury bonds increasing in value. The break in this pattern indicated both perceived and real needs for cash. Whether it was led by thousands of individual investors or a number of large hedge funds or both, the result was indiscriminate selling of assets that could provide immediate liquidity.24

By March 13th, Europe had become the epicentre of the COVID-19 outbreak.25 In the U.S., President Donald Trump declared a national emergency and initiated a fiscal policy response, opening up $50 billion in federal funding to manage the impact of the outbreak26 on individuals and businesses. Canada also announced a $10 billion economic stimulus measure, bringing its total fiscal policy response to-date to $11 billion.27 These fiscal policy measures would prove to be small drops in the bucket, relative to what was deemed necessary a few weeks later, as infection rates grew and business closures and job losses far exceeded initial estimates.

On the same day, Apple flipped geographies in its implementation of precautionary measures and began to re-open stores in China, while closing all retail stores outside of China.28 Employees outside of Greater China were asked to work remotely if their job allowed and efforts to reduce density and maximize social distance to protect the health and safety of employees and customers were prioritized. This foreshadowed a mass movement by employers to have employees work from home. The constraints on individual freedoms catalyzed by this move did not go unnoticed. The following week, Angela Merkel, Chancellor of Germany, shared the difficulty of imposing restrictions on personal freedoms for someone who grew up in East Germany under the Stasi: “For someone like myself, for whom freedom of travel and movement were hard-won rights, such restrictions can only be justified when they are absolutely necessary.”29

The weekend of March 14th-15th, central banks worked to enact new monetary stimulus measures to shore up investor confidence in the face of rising fears. At 5:00 p.m. on March 15th, the Federal Reserve decreased the federal funds rate by 1% to between 0% and 0.25%30 and announced a plan to buy $700 billion in bonds to help provide liquidity to the markets. The next day, Canada’s central bank followed with its own policy rate cut to 0.75%.31 The European Central Bank, under Christine Lagarde’s leadership, did not cut its key interest rates (already historically low at 0% to -0.50%) but had just announced a pandemic emergency purchase package at its meeting on March 12th.

Most investors were surprised by this latest central bank response. They responded negatively to central bank actions, viewing them as a signal that the worst possible outcome of the coronavirus pandemic would be realized.32 In retrospect, March 16th was a day that tested the limits of the financial markets. When the stock markets opened that Monday morning, prices declined precipitously and U.S, circuit breakers were triggered for a third time, halting trading for 15 minutes. The selling resumed however and by the end of the day, the S&P 500 had dropped 12%. Volatility, or “fear,” in the markets was of epic proportion, with the VIX reaching an all-time high of 82.69. Many investors were forced to sell their positions because they needed cash to cover margin calls or meet debt payments.

In the bond markets, it became clear that the announcement of the Federal Reserve’s plans to buy $700 billion of bonds was not enough to halt a liquidity crisis. Investors were selling government and corporate bonds at any price. Their unwillingness to lend impacted even the highest quality credit corporate institutions and governments.

There was less bond issuance during that week than at any point during the 2008 financial crisis, the 2001 terrorist attacks, or even 1987’s Black Monday.32

The dysfunction was expressed most extremely in money market funds. A traditional “safe” asset and “cash equivalent”, a money market fund invests in short-term government and corporate debt. However, on March 16th, buyers for bonds held within money market funds were nowhere to be found. This triggered a loss of confidence in the liquidity and ongoing safety of these funds. U.S. investors panicked and placed sell orders to get out of money market funds, but the widespread panic meant fund managers had no buyers for the underlying assets. The market was frozen.32

Between March 15th and 31st, the Federal Reserve launched a range of measures to increase liquidity in financial markets. This included a deal to reduce rates on currency swaps with the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank and the Swiss National Bank, newly established temporary U.S. dollar swap lines with the Central Banks of Australia, New Zealand, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Brazil, Korea, Mexico and Brazil. Also promised were unlimited, open-ended large-scale asset purchases, including purchases of corporate and municipal bonds and mortgage-backed securities. 33

On March 18th, Canada announced an $82 billion economic stimulus package. The package provided up to $27 billion in direct support to Canadian workers and businesses, plus an additional $55 billion in tax deferrals to meet liquidity needs of Canadian businesses and households.34

On March 19th, the Bank of England made the second cut to its base rate in eight days, dropping it from 0.25% to 0.1%35. The Reserve Bank of Australia also cut its cash rate to an all-time low of 0.25%.36 The U.S. dollar was reigning supreme as the world’s reserve currency.37 The Canadian dollar hit 68.2 cents per U.S. dollar, a four year low.38

In a White House press conference on March 19th, U.S. President Trump blamed China for a lack of transparency around the true extent of the outbreak in China, stating that the “world is paying a very high price for what they did.”39 Since then U.S. and China relations have deteriorated, compounding an ongoing economic trade war between the world’s two largest national economies. The standoff contributed to the noted absence of United Nations Security Council action during the crisis, putting into question the relevance of supranational organizations in today’s world.40

By March 23rd, London’s Heathrow Airport had shut down two of its four terminals, and passenger traffic had almost ground to a halt. Its 76,000 employees suffered a 10% pay cut and 500 managers were laid off. Operational costs were still running at 50 million pounds per week. This was a prime example of an infrastructure asset believed, a mere few weeks before, to be a stable, consistent revenue and profit generator, the type of asset sought by pension plans and sovereign wealth funds around the globe.41

On the same day, the S&P 500 closed at 2237.4, down 2.9% from its previous close. This turned out to be the low, at least for now, and marked a peak to trough drop of 34% in just 23 trade days. For context, it took approximately 300 days for an equivalent drop in the markets during the Global Financial Crisis, starting from the early signs of the crisis on August 7, 2007.42

Long-term value investors were focused on assessing the impact of the pandemic on the intrinsic value of businesses. For companies, “cash was king,” and it became clear that those with sufficient liquidity on their balance sheets to maintain operations and manage the short-term pressures on their businesses, would be the most resilient through the pandemic and emerge on the other side in a stronger competitive position. On the same day that the S&P 500 reached the March 23rd lows, Bruce Flatt, CEO of Brookfield Asset Management, reminded investors to focus on the intrinsic value of investable businesses: “Finally, a reminder regarding investing in times like these: the underlying value of a business that trades in the public market does not change on an hourly basis. Despite the fluctuations, you own a part of an actual business (or businesses), not a piece of paper or electronic symbol that adjusts on a minute-by-minute basis. Acknowledging that the value of some businesses has changed, at least in the short term (airlines being the most extreme example at the moment), the long-term value of many companies has not changed substantially over the past few months.”43

MARCH 24 -APRIL 30

As investors began to understand the extent of the Federal Reserve’s commitment to provide liquidity to the credit markets, buyers came out in droves on Wall Street and around the globe. On March 24th, the S&P 500 rose 9.4%, the MSCI ACWI rose 8.1% and here at home the S&P/TSX had its biggest gain since July of 1979, rising 12%. On March 25th, the U.S. Senate approved an historic US$2 trillion fiscal stimulus package, the largest of its kind in modern American history. The stimulus provided for direct payments and jobless benefits for individuals, money for states and a huge bailout fund for businesses.44

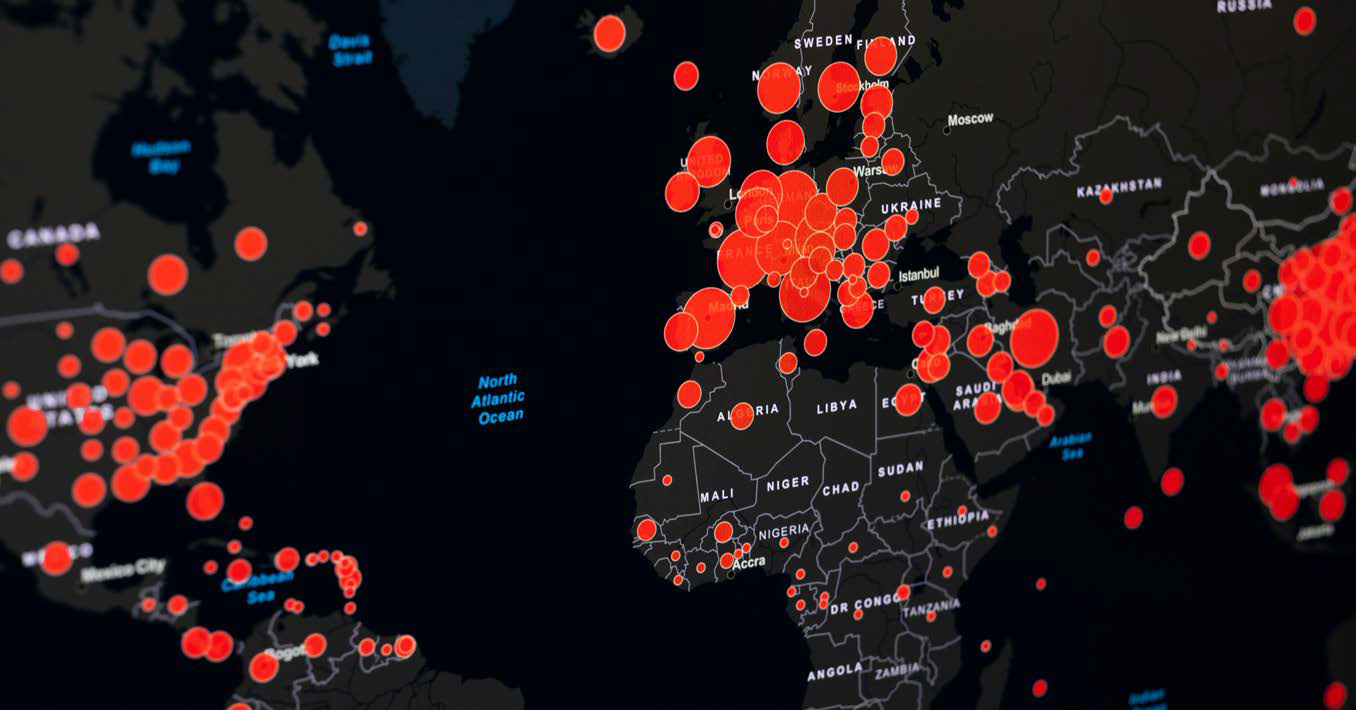

By March 26th, the U.S. led the world in COVID-19 cases and New York City became the epicenter of the outbreak.45 By April 2nd, global cases of the novel coronavirus hit 1 million46 with little evidence of a break in momentum.

Canada continued to enact monetary policy stimulus measures, with the central bank cutting its policy rate to 0.25% on March 27th.31 The speed of central bank action around the world during the coronavirus crisis was unprecedented. During the Global Financial Crisis, it took central banks almost 500 days from August 7, 2007, the point that they deemed it necessary to ease, to bring policy rates down to levels of 0.25%.42

Businesses began to mobilize their strengths to meet the needs of the broader community. In late March, Linda Hasenfratz, CEO of Linamar, the Guelph, Ontario based global leader in auto parts production, and 2016 Women of Burgundy keynote, announced an initiative to team up with other auto parts makers to produce 10,000 ventilators. She said, “It’s given us something to focus on. We’ve been able to bring folks back from layoffs for these different programs we’re working on and given them something to do that they actually feel really good about”.47

On April 9th, the oil price war ended when OPEC and Russia agreed to reduce oil output by 10 million barrels/day.48 Still, the fallout continued. On April 20th, the price of WTI oil for May delivery expiring on April 21st, sold into negative territory (-$37/bbl) for the first time in recorded history due to depressed demand and insufficient storage capacity.49

By mid April, Apple had reopened a retail store in South Korea, its first store outside of China to re-open during the pandemic.50

Warren Buffett, Chairman and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, was notably quiet during the first few months of the crisis. However, on April 17th, his long-time partner Charlie Munger, Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, provided some observations. He said, “Nobody in America’s ever seen anything else like this. This thing is different. Everybody talks as if they know what’s going to happen, and nobody knows what’s going to happen.” He also shared the strategy for Berkshire Hathaway’s business. “Warren [Buffett] wants to keep Berkshire safe for people who have 90% of their net worth invested in it. We’re always going to be on the safe side. That doesn’t mean we couldn’t do something pretty aggressive or seize some opportunity. But basically, we will be fairly conservative and we’ll emerge on the other side very strong.”51

World markets rallied over the month of April. The MSCI ACWI rose by 10.4% while the S&P 500 closed up 12.8% for the month. At the end of April, this swift recovery meant that the S&P 500 was down just 9.3% on a year-to-date basis (January 1st–April 30th), outperforming major markets around the world. The U.S. market was buoyed by stock prices of large technology companies such as Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Netflix, Google and Microsoft, whose business models proved resilient in the early stages of the novel coronavirus crisis.

“Nobody in America’s ever seen anything else like this. This thing is different. Everybody talks as if they know what’s going to happen, and nobody knows what’s going to happen.”

Around the world, markets had varied responses. On a year-to-date basis, as of April 30th, the Canadian market was down 12.4% (S&P/TSX Composite Index), the European market was down 17.2% (MSCI Pan-Euro Index), the Asian market was down 11.7% (MSCI AC Asia Pacific Index), and the Emerging Markets were down 11.9% (MSCI Emerging Markets Index).

At the time of writing, investors remain cautious about the road ahead. Unemployment levels in Canada and the U.S. soared to 13% and 14% in April respectively, the worst levels since the Great Depression.52, 53 Companies are releasing their Q1 reports, providing some transparency about the true impact of the coronavirus lockdown on businesses globally. The equity rally seems to be out of alignment with business fundamentals, reminding investors that in the short term, market prices and business fundamentals do not necessarily align.

We are now in the midst of countries around the world experimenting with re-opening of their economies, balancing health and safety with economic concerns. As of June 15th, there were a total of 8 million confirmed COVID-19 cases and 437, 404 deaths from the virus world- wide.54 There remain many more chapters to be written about this historic time.

* For endnotes, access the PDF article via the “Download PDF” link at the top of this post.

This post is presented for illustrative and discussion purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment advice and does not consider unique objectives, constraints or financial needs. Under no circumstances does this post suggest that you should time the market in any way or make investment decisions based on the content. Select securities may be used as examples to illustrate Burgundy’s investment philosophy. Burgundy funds or portfolios may or may not hold such securities for the whole demonstrated period. Investors are advised that their investments are not guaranteed, their values change frequently and past performance may not be repeated. This post is not intended as an offer to invest in any investment strategy presented by Burgundy. The information contained in this post is the opinion of Burgundy Asset Management and/or its employees as of the date of the post and is subject to change without notice. Please refer to the Legal section of this website for additional information.