An evening with Zita Cobb

On August 19, 2019, over 180 chief executives of many of America’s largest companies issued a statement challenging the concept of business as we know it. The prevailing view of the last 50 years or so had been that the primary goal of business is to maximize shareholder value, which was seen as the best way to deliver goods to the public, optimize employment and ultimately, create wealth.

But on August 19th, the Business Round-table, representing 181 CEOs of companies as large as Apple, Amazon and Walmart, rejected the conventional wisdom and countered that businesses have a commitment to multiple stakeholders—inclusive of shareholders, customers, employees, suppliers and communities. This was more than a change in thinking; it was a fundamental change in belief marking a momentous shift away from seeing business as a purely profit-maximizing tool, to one that pursues both profit and purpose.

As investors, what are we to make of this? The skeptics in us might simply see this as a public relations stunt. After all, the act of signing the statement of purpose does not commit CEOs to actually change their actions. Legally, corporations and their boards of directors are bound by corporate laws that dictate a fiduciary duty of care to their shareholders. There is also the issue of accountability. If earning returns for shareholders is no longer the primary purpose of the corporation, who is the corporation accountable to?

It’s important for us to appreciate that shareholder profits and a commitment to customers, employees, suppliers and communities are not mutually exclusive. Just ask Zita Cobb, Founder and CEO of the Shorefast Foundation, and our Women of Burgundy guest speaker on October 30, 2019.

Zita is decidedly unambiguous in her belief that business is an effective tool to achieve social ends. She made her mark in the corporate sector as a senior executive at JDS Uniphase, helping to build one of the most successful high-tech companies in both Canada and globally. She spent the next 16 years of her career building and operating the Shorefast Foundation, a non-profit social venture responsible for reviving the small Newfoundland community, where she was born and raised. In 2016, Zita was awarded the Order of Canada for her remarkable contributions to the cultural, social, and economic resiliency of the Fogo Island remote fishing community.

The following is an excerpt of Zita’s remarks to the Women of Burgundy

I’m going to talk about belonging, and how individuals, companies or communities belong to the world. We live in a world that makes it exceptionally difficult to belong. The crisis of belonging is really a crisis of value; the financial value of things as opposed to their inherent or intrinsic value. Understanding intrinsic value is essential to not just survive and thrive, but to make meaning. I’m going to talk about all these things through the lens of a place called Fogo Island, and through the lens of my own life.

Three Centuries

Three Centuries

I am 61 years old and I have lived in three centuries. Until I was 10, I lived in the 19th century. I am an eighth-generation Fogo Islander, who grew up without running water or electricity. It was a pretty perfect life. We understood deeply what community was and had a rich sense of ecological logic. We were very well acquainted with the idea of “enough.”

We also had a deep sense of social logic. The year I was born, 1958, the island was at its peak population. There were 6,000 people spread among 10 communities. You might not be all that happy with your neighbour, but you knew you had to muck along together. That mucking along together, and that ability to navigate multiple truths and carry on, was an important part of the social fabric.

When I was 10, the worst of the 20th century came down on top of us in the form of the industrialization of the fishery. Enormous ships appeared on our shores and overnight, everything we knew as a culture and as a people, was irrelevant. We came within a hair’s breadth of being resettled. That was the 20th century.

My business career took place during the 21st century. It was in wave-division multiplexing, little tiny optical components that have enabled the digital revolution.

The centuries are going by in decades now. Maybe I’ll see a few more of them. I hope so, because there is still lots of work to do.

Everything is Local

In life, everything eventually comes back to its local roots. Even in this new multiple stakeholder economy, we have to start with the local, and then network all of those locals together to make a country, to make a planet.

I think of Fogo Island as an example of what happens in a positive way if we can pay attention to the local. A small island is a pretty good proxy for a small planet because on these small islands we can see cause and effect. They are like laboratories. Maybe it’s not a perfect proxy, but I think we can learn something.

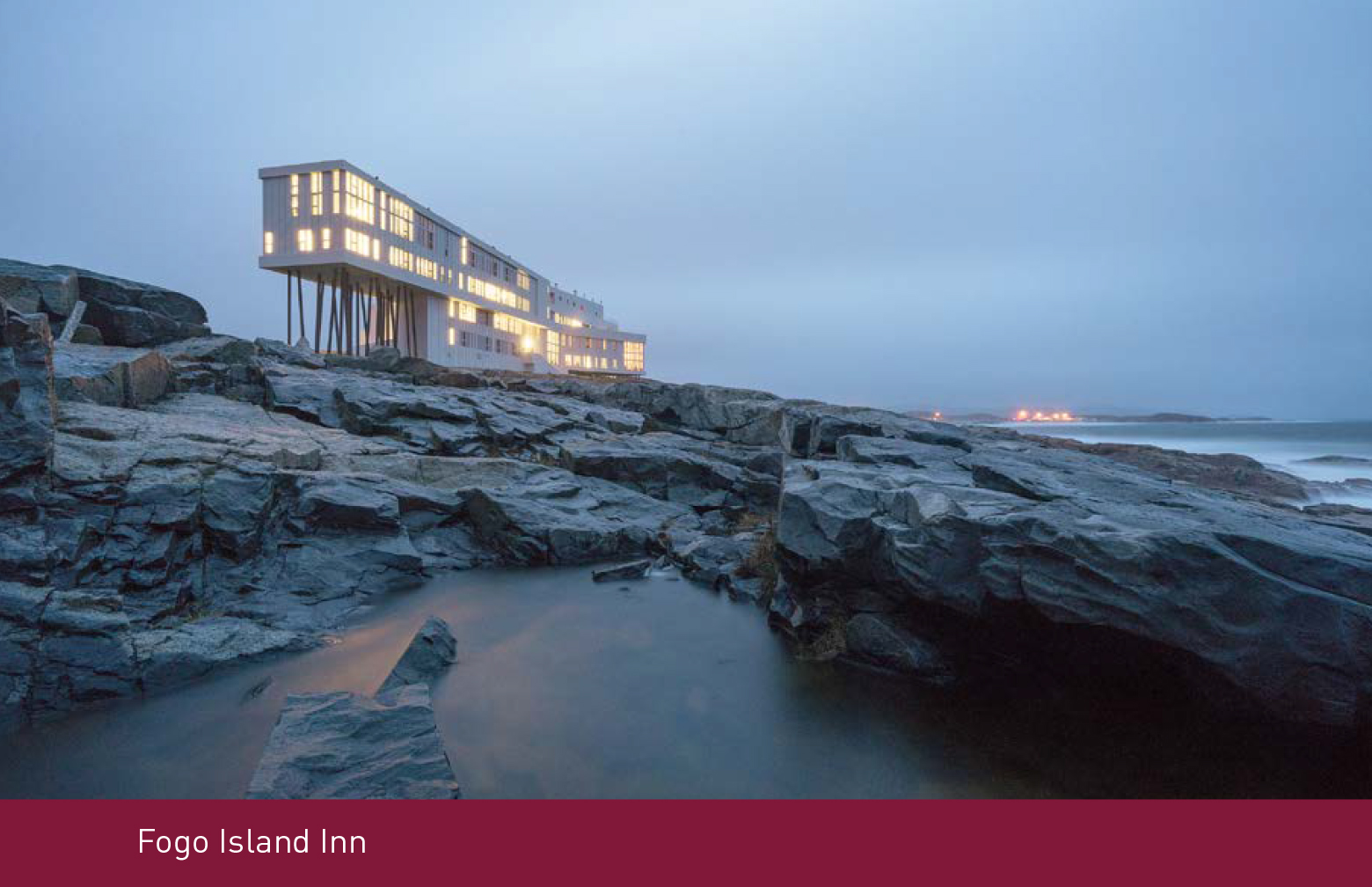

The Fogo Island Inn opened in 2013. I call it a Trojan horse for a set of ideas. Every time I say Fogo Island, you have to fill in the name of a community that means something to you. If you don’t have one, I highly recommend you get one straight away because it is going to change how you see the world, and it will make life a lot less confusing.

Communities Matter

The economist E.F. Schumacher wrote Small is Beautiful in the mid-1970’s. I think his work is really important and useful to finding our way forward. He believed that you get to big things by starting with the small ones, and then put them together in intelligent ways.

He wrote: “Nature and culture are the two great garments of human life. Businesses and technology are the two great tools that can and should serve them.” I never met a person who would disagree with that, but I do meet lots of people who don’t act as if it were true.

Business is a fantastic servant, but it is a dreadful master. We invented business and it is the best way I know of getting things done. When we get up in the morning and go to work or wherever we go, what are we optimizing for? Imagine how the world would be different if we all got up in the morning and optimized for some notion of human community. When I say community, I mean a place where people are interconnected and live in some kind of a tangle with one another.

We understand ourselves by living in communities with other human beings. Communities create a solid foundation for navigating the bigger world. In many communities, especially a place like Fogo Island, people have shared memories and shared aspirations. That is very orienting. But, if you separated every person on the planet from their personal and family histories, they would feel a bit lost.

Communities Versus Networks

Communities Versus Networks

I want to distinguish between a community and a network. A network is typically an online relationship, which is both valid and important. But, for owners of Subaru cars to say they are part of a Subaru community, is a misuse of the word community. They are part of a Subaru network. Networks are also very important, and they should be used to strengthen communities.

Community involves love and sustainability. In Newfoundland, an acceptance of precariousness is a prerequisite to permanence. If there is anything we know on Fogo Island, it’s that life always feels precarious and it’s felt like that for 400 years.

We all want to belong together. But, the question is, how do we create a global network of intensely local places? I don’t want to come to Toronto and find Chicago, but the nasty form of globalization that flattened places around the world started in 1970 with Friedman and was made worse by Jensen and Meckling in 1976.

Sacred Capital

I studied business, and I worked in business, and I still work in business. I read Sacred Economics by Charles Eisenstein, who proposed the idea of sacred capital. When he says sacred he doesn’t mean anything to do with spirituality. He just means something that carries a unique essence that cannot be easily replaced. Cultural capital, social capital, natural capital, human capital and physical capital—all of these are sacred things. Then there’s money, which is hugely important but not sacred. I think getting this relationship right is the work of our time.

An even bigger question than what is the purpose of business, is what is the purpose of money? We invented it. It’s just a thing. We invented technology, and that’s just a thing. Humans are like teenagers in our understanding of our relationship with money and with technology.

Fogo Island

Fogo Island is about 20 miles off the Newfoundland coast and consists of 10 little communities. Let me give you a sense of how isolated it is. I grew up in Joe Batt’s Arm. Tilting, which is an all Irish commu- nity, is five kilometers away and I went there for the first time when I was 13. There was no reason to go before that. We didn’t have cars and we had everything we needed in our own community.

Before building a house, Fogo Islanders would first build a fishing stage; a staging area between the ocean and the land for people to get out of their boats. You had to get a fishing stage first so you could get your boat in with enough water depth to get there when the tide was low. It is an inspirational space that fires up the imagination of most Newfoundlanders because it’s that liminal place between the water and the land.

Every April, a pack of ice comes from Greenland; it is multi-year ice and is super thick. You could get up in the morning and all the harbours and bays might be jammed up with it, and when the tide changes, every- thing changes. Living there is like living in a place that you ultimately have very little control over.

A Fishing Culture

To understand the culture, we have to go back in time. In 1497, soon after Christo- pher Columbus, John Cabot was sailing the Atlantic in search of India. He bumped into Newfoundland and sent a letter back to the king that said, “Sire, the fish are so plenty; they stay the progress of my ships.” He had found one of the biggest fish populations of any ocean, the North Atlantic cod. This fish is the noblest fish on the planet because it has more protein than any other fish, which is why it lends itself so well to the salting and drying.

For 350 years, we were inshore cod-fishing people. In Newfoundland when someone says fish, they mean cod. There’s no better example of a culture on the planet that is inextricably linked to one creature, and it’s this fish.

We fished close to the shore, never more than five miles out. We made our own boats and made our own nets. That net is tied to the shore by a rope, a tether called a “shore- fast.” That’s why we named our foundation Shorefast. It is a metaphor for may we always be shorefast here in this place.

This fishing went on like this for 350 years, until the industrialization of the fishery. It then took 30 years to bring the cod to the brink of ecological extinction. Almost all of the islands of Newfoundland were resettled, but not Fogo Island, because of a miracle that came in the form of art.

In 1968, the National Film Board, which is one of our greatest national institutions, had a program called Challenge for Change. They were looking at poverty and sources of poverty and what we could do about it. A talented filmmaker from Montreal named Colin Low arrived and made 27 beautiful short films, called the “Fogo Process.”

Up to that point, we were 10 little communities that didn’t know each other. It wasn’t until the Fogo Process that we got together.

In 1967, we formed the Fogo Island Cooperative Society, which owns the fishery on Fogo Island to this day.

The Right Business Solution for the Problem

Business people are not typically very nuanced. Business education generally lets us down because we don’t study art or sociology. Business grads, and I’m one of them, are often people who are like robots that know how to do one or two things that are actually downright dangerous when you do them without understanding the context.

To run a fishery on a little island off the coast of Newfoundland, you don’t need an enormous publicly traded company that’s under pressure for quarterly results. If such a company owned the three fish plants on the island, they would have been shut down. The co-op makes money, it just doesn’t make lots and lots of money. Therefore, those fish plants are optimizing for community well- being, not for maximum profit.

If you need to drill for oil and gas off the coast of Newfoundland, which we are doing, bring on the transnational capital. We need the big companies; we need to get some financial engineering behind this. So, it’s about getting the right business solution for the problem you are trying to solve. If you’re not trying to solve a problem, why are you in business in the first place? How did you get a social license? We don’t print social licenses for the sole purpose of making money.

The moratorium on cod fishing has been in place since 1992, and the cod are coming back ever so slowly. The only fishery we have now is a stewardship fishery. Our main fisheries and our little co-op have figured out how to adapt to other species: crab, shrimp, and Greenland halibut, which we call turbot.

My father could not adapt to the mid-shore fishery because he couldn’t read and write, and he couldn’t learn to use the charts. He died never really understanding what happened. He used to say, “Who in their right minds would fish day and night until all the fish are gone? That just makes no sense.” He insisted that I study business because he said if you don’t study business you are never going to understand how the world works.

Cauliflower Fractal

I studied business which was important. But, more important, I got a job at a grocery store on Elgin Street in Ottawa. It was there that I saw cauliflower for the first time and I realized that this was a beautiful fractal, a pattern that repeats and repeats. I also realized that Fogo Island is one of those tiny little florets. Toronto is a bigger floret, and Beijing is an even bigger floret, which all are held together by the stem. The stem has two jobs to do. Number one job is to hold us all together and number two is to bring nutrition to the florets. This includes economic nutrition, which of course the fishing companies failed to do back in 1967. The cauliflower has become the metaphor for how I see business. At Shorefast, we have little cauliflower lapel pins that we put on every morning to remember what we are supposed to be doing.

Schumacher said, “Our task is to look at the world and try to see it as whole.” That means whatever we do, whatever actions we take, think about how it is going to affect her, and him, because it matters. There are organizations in the world that I find hugely encouraging. They are trying to measure all of this progress we’ve made. I know the Economist was deeply skeptical about how all this would be measured. But, we can measure it. Some say the collapse of the cod was a failure of public policy, but it was actually a failure of accounting. Who was counting the fish left in the water?

Why Shorefast?

After I finished my career at JDS Uniphase, I went sailing for a few years and figured out what I wanted to do, which was to go home. I moved back in 2006 and, using the money I had made from my career at JDS, I set up a Canadian registered foundation with two of my brothers. We then worked with the people of the island to figure out what we should do. We could have taken that money and divided it up 2,600 ways and given everybody a little bag of money, but that wouldn’t have added up to much. I realized the fishery on Fogo Island was essential, but not enough to keep the economy going. What we were really preoccupied with, was building another leg of the economy that could complement the fishery and also strengthen the culture.

Asset-Based Community Development

Nobody ever built a future based on what they don’t know and don’t have, and noth- ing changes in the community until you do what John McKnight says, which is focus on the assets.

“Surely we are good for something,” as my dad would say. With asset-based community development, you focus on assets and you ask: “What do we have? What do we know What do we love? What do we miss? And what can we do about it?” As soon as you get to the “what can we do about it,” we start doing something. We went through that process on Fogo Island and realized that we are people who are genetically and culturally predisposed to profound hospitality.

With the money invested in the foundation, we built assets that would be held by Shorefast Social Enterprises. The biggest one is the Fogo Island Inn, which cost $41 million to build and has 29 rooms. People would say to me, “Who in their right mind would spend $41 million on a 29 room Inn? Wasn’t that a big risk?” Of course, no one wants to lose their money, but I was much more concerned with losing a whole culture and that, to me, was the bigger risk.

We built the Inn and that led to a furniture business. We also have Fogo Island Fish. If you eat at some of the nicer restaurants in Toronto, you’ve probably seen our fish on menus. That’s a new little business because we catch them one by one in the fishery and bring them straight to you with a lot of love.

We also have a business assistance fund, which is like a micro-lending fund. We lend money to people to start and expand businesses on Fogo Island, and keep the business ecology working. We run a whole set of charitable programs, the biggest one being Fogo Island Arts, which is about holding onto knowledge through heritage. We used to be boat builders, and while we don’t need those little wooden boats anymore (because our fisheries have changed), we need to find ways of preserving and passing on the knowledge that is in the making of the boats. We are also on the verge of starting a community economics institute focusing on how to strengthen communities, which are at the centre of the economy.

The charity owns these assets and operates these programs, all of which are social businesses. We target 15% profit in all of our businesses, but we don’t always get there. We reinvest that profit into the charity and put it back into programs that support the island.

Twelve years ago, I started saying that businesses should be not-just-for-profit. I could feel people rolling their eyes but good business people were always not just for-profit. It may seem like a contradiction, but life is a rhythm of opposites. We have to learn how to navigate a multitude of truths. I think I’ll live long enough to see all business become social business.

Bringing Contemporary Architecture to Fogo Island

Architecture helps us mediate the relationship between the past and the future. Though we had been building little wooden houses on Fogo Island for 400 years, our local builders lacked any sense of contemporary architecture. Our architect, Todd Saunders, grew up in Gander and the complicated drawings he sent to our builders made no sense to them. So we built a model, one inch to one foot, and then scaled it up.

We started with four studios, all of them off the grid; collecting rainwater and using solar panels, composting toilets and wood-burning stoves.

Once we got the studios built, we felt like we had some experience building contemporary architecture and we were ready to tackle the Inn. We put in 80% of the money and then went to the federal and provincial governments and told each of them,“You have to give us 10%. And I don’t mean lend us 10%. Give us 10%.” Governments want to do the right thing for communities, but they don’t always know what that is. The first letter that we got back essentially said that this is “not normal, practical, reasonable, or rational.” Having come from the technology business, I knew that when you got a letter like that, you know you are on the right path. So, we pressed on. To their great credit, both governments came on board with us, and both have gotten their money back many, many times over.

We talked about what to do and how to do it for seven years. Then we got building. It took us only three years to build the Inn and it was built mostly by Fogo Islanders.

Putting this building on that site was not easy. It’s 300 feet long and 30 feet wide. It’s a wooden inside-and-out building, and every board in that building was touched by human hands 14 times. Now you know why it cost $41 million.

The Inn is like an “X” and it carries the rhythm of opposites. That is the design of life. It is for people from the island and it is for visitors from away. It is about the past and it’s about the future. I’m most proud of the fact that it is an act of human culture, an act of community. Architectural Digest called it “One of the most daring new buildings on the planet.”

Economic Nutrition

The quality of our lives is in the quality of our relationships. The quality of our relationships is the quality of our awareness. The awareness of the people in the system.

Nutrition labels tell you all the ingredients in a food product. Most people would never think to eat something that didn’t have a label. We copied that model and started to do “economic nutrition” labels. For everything we sell, we tell you where the money goes. The economic nutrition label for a stay at the Fogo Island Inn would say that “49% of what you spend to stay there goes to the people who work there.” I can tell you that the figure of merit in the hotel industry is 30%, which is why most people who work in the hotel industry have two or three jobs. As for what we spend on supplies and commissions, we target 15% profit.

The next time you go into a store to buy something like a jacket, or even a loaf of bread, ask the merchant if he or she has the economic nutrition label for that product. They should. Everybody can do this. As soon as we have economic nutrition labels, we stop being consumers and start being citizens. We can put our money behind the things we value most.

We do economic nutrition labelling for the fish business too: 69% of the money that you spend in Toronto to eat that fish goes straight back to Fogo Island. I think my father would be proud of that.

Right Pricing

We had to decide how many rooms there would be in the Inn. Conventional logic in the business world would be to build a lot of rooms to justify all this expense on equipment and restaurants. But, in our community conversations, one woman said, “We are 2,500 people and we can love only so many people at a time.” We settled on 30 rooms and then I realized that’s not a prime number, so we decided on 29, which is a prime number. If you settle on 29 rooms and remember, this Inn was built to make a material difference to the economy at Fogo Island, you know you’re not dealing with a $300/night Inn. For the pricing to be financially sustainable, we did something we call right pricing.

I have a fairly wealthy friend who told me the Inn is very expensive, and I said, “Oh, I have a few ideas for how to make it cheaper for you. You see that guy working over there…we could pay him minimum wage and that would probably save you a couple hundred dollars. But we don’t pay him minimum wage, we pay him a lot more because where else is he going to work? We could dump raw sewage in the ocean and lay off those five guys that manage the system. That would save you another couple hundred dollars.” The point is, it’s a choice people make.

Our Relationship with Objects

The building itself was hard, but the interior was actually harder because we decided to make everything possible on the island to generate more economic activity.

You can’t take a chair from 1850 and put it in an Inn that opened in 2013. We started a designer and residence program, and invited designers to come from around the world. We matched them with local makers and asked them to come up with the new objects. Women on Fogo Island can make anything out of textiles. Men can make anything out of wood. We figured we could make it work.

Elaine Fortin from Montreal designed a wooden chair, which I think is a rock star in the collection of all the furniture. The legs of the chairs grew out of the ground that way. We can only make about 10 of these chairs a year because it’s hard to harvest the wood properly.

We should expect a lot from a chair. Besides its function, there is beauty. We have relationships with objects. Consumerism is not that we love things; it’s that we don’t love things. That’s why they go to the landfill. If you come home to a house full of objects that are anonymous and have no meaning to you, that’s not going to be a good homecoming. If you come home and all of the chairs are welcoming you home, that’s a lovely thing. By buying something, you are creating a relationship with its maker. The more you know about who made it and where the money went, the richer your life.

Buy and Cook Local

We decided from the beginning to cook what is local: 80% of what we serve comes from within our close reach and 20% is imported. We forage, we hunt, we fish and we farm. But you can’t run an Inn without wine, chocolate and olive oil, so you have to be reasonable. Every once in a while, our chef, Johnathan Gushue, a Newfoundlander, will say, “Why don’t we have a garden?” I say, why do we need a garden? Everybody grows on the island. Buy from them, support the local economy. That’s the point of the business.

We want our food to be nutritional and tasty and to support the local economy. But, we also want the Inn to act like an electric eel that starts conversations about food. Where does our food come from? Can we inspire more people to start growing their own food? When I left home, Newfound- land was producing about 80% of our own food. We then fell into that industrial food trap, but now we are slowly making our way back to producing more of our own food.

The Ongoing Creation of Communities

We are all, each and every one of us, responsible for the ongoing creation of our communities.

Building communities is everyday work. When we see something that needs to be done, we do it in the belief that it is going to affect somebody else. It may give them courage for their work.

Never be overwhelmed, or allow yourself to be discouraged, because something seems like a big task. Just do what you know how to do.

Everything that everyone does matters a lot. It all adds up. Jane Addams, a housing activist in Chicago who won the Nobel Prize in the 1930s, said, “The good we secure for ourselves is precarious and uncertain until it is secured for all of us and incorporated into our common life.” Our common life is our community life, and that starts with our community economies.

“We are all, each and every one of us, responsible for the ongoing creation of our communities.”

This post is presented for illustrative and discussion purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment advice and does not consider unique objectives, constraints or financial needs. Under no circumstances does this post suggest that you should time the market in any way or make investment decisions based on the content. Select securities may be used as examples to illustrate Burgundy’s investment philosophy. Burgundy funds or portfolios may or may not hold such securities for the whole demonstrated period. Investors are advised that their investments are not guaranteed, their values change frequently and past performance may not be repeated. This post is not intended as an offer to invest in any investment strategy presented by Burgundy. The information contained in this post is the opinion of Burgundy Asset Management and/or its employees as of the date of the post and is subject to change without notice. Please refer to the Legal section of this website for additional information.