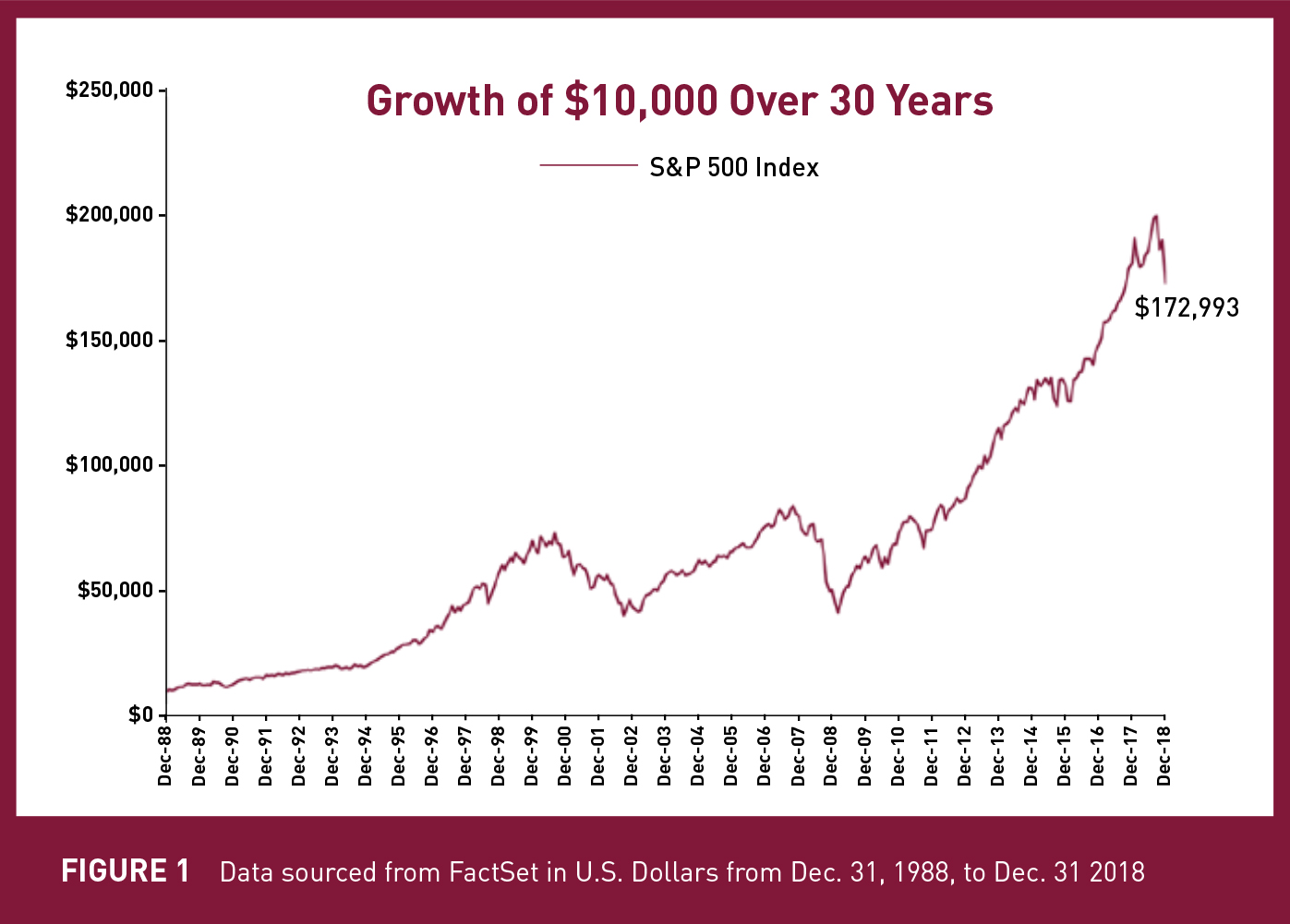

The past 30 years have truly been a spectacular period to be invested in stocks. A US$10,000 investment in the S&P 500 Index at the end of 1988 would have grown to just under US$173,000 by the end of 2018—a 17-fold increase achieved simply by buying and holding (Figure 1).

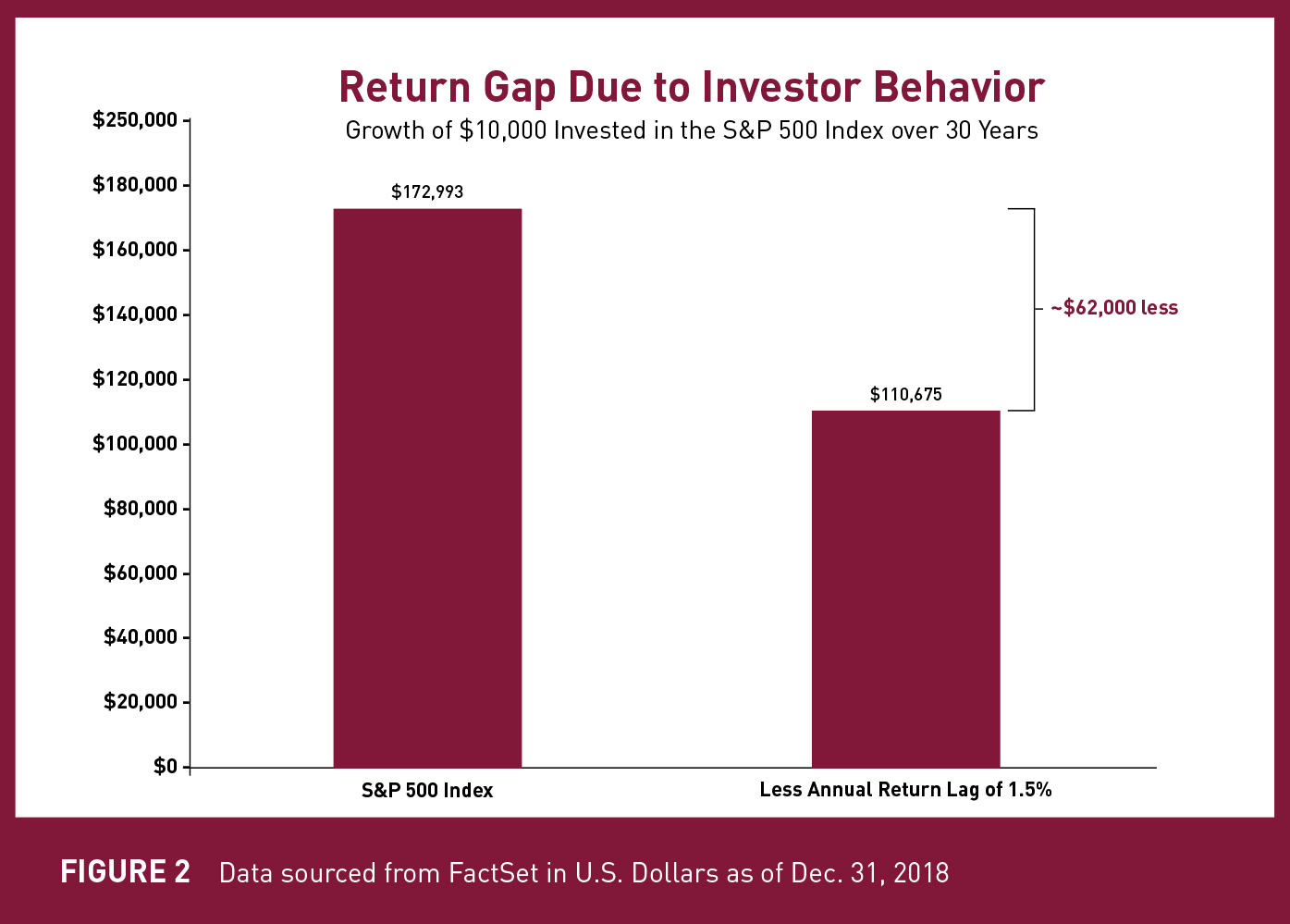

Yet many studies have shown that we struggle to capture the full benefit of these types of opportunities to compound our capital. According to research by Morningstar, the portfolio of the average Canadian routinely lags the performance of the strategy they have invested in. This lag can range from 1% to 1.5% per year. This may not sound material, but over long periods of time, the difference can be significant. If we apply an annual performance lag of 1.5% to each of the 30 years mentioned above for the S&P 500 Index, the initial US$10,000 investment would be worth just US$111,000, a full 36% less on a cumulative basis. (Figure 2).

Mental Model: Inversion

The obvious question is, why does this gap exist?

To answer this question, we propose using a problem-solving framework called inversion. The theory behind this approach is that it is not enough to think about difficult problems one way. If we want to improve our understanding of a problem, we need to think about it forwards AND backwards.

As an example, if we want to increase the growth of our portfolio, thinking forward, we may seek out all the investment tools and approaches that promise high potential returns.

If we look at it through an inversion lens, we would think of all the factors that might hurt our performance. Ideally, we would avoid these.

Applying this framework to investing was made famous by Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett’s long-time business partner at Berkshire Hathaway. At age 95, Charlie has a wealth of experience and says he spends less time trying to be brilliant and more time trying to avoid obvious mistakes. This seems to be a reasonable objective for all of us.

With this in mind, we present three common investment mistakes and our recommendations for avoiding them.

Mistake #1: Not Doing Your Homework

From time to time, a new product or business emerges that captures the imagination of investors. It may even become the latest hot investment tip in office discussions or at dinner parties. Enamoured by the potential of a new opportunity and driven by the fear of missing out, people may allocate their savings to it, regardless of value.

It is curious that human beings will often act on investment tips without doing much research. Conversely, if we buy a new car or appliance, we often spend hours researching its features, reading reviews and comparing prices. We usually decide based on quality and value. In contrast, in the investment world, we are often willing to act simply on the word of someone else, or because the price is trending upwards.

Consider the example of Bitcoin, which captured the imagination of investors in early 2017. The price of Bitcoin increased from roughly US$1,000 to US$16,000 by the end of 2017.

Bitcoin is a form of digital currency that was supposedly created by an unidentified person or group that goes by the name of Satoshi Nakamoto. Bitcoins are awarded to computers that are the first to solve a limited number of challenging math problems. The main excitement about Bitcoin is based on the idea that it offers the potential to revolutionize the way we transact.

How can an investor value Bitcoin? It is not a business with income, dividends or tangible assets. Could we assess Bitcoin like a currency? Bitcoins are not attached to a national economy. They are not stabilized by a central bank. And in late 2017, some governments were banning the use of them. If no one accepts Bitcoin as payment, would its intrinsic value be zero?

By early 2018, the price of Bitcoin had dropped significantly. We believe a lack of investor confidence in how to value Bitcoin meant that there were too few investors willing to stabilize the price when volatility arose.

This may seem like an extreme example, but we have seen this behaviour play out time and again. Many will recall the dot-com boom in the late 1990s, when Internet start-ups received sky-high prices despite many of them having no earnings or realistic business plans.

Conducting research helps us understand our investment on a fundamental level. Having a good understanding of the business in which we are considering investing helps us to remain level-headed in the face of irrational investor behaviour.

How do we avoid the mistake of irrational investing?

Our recommendation: First, do your homework. Know what you are buying. There are no shortcuts. Second, be selective. A framework suggested by Warren Buffett is to imagine you have a punch card with only 20 investing slots in it. Those 20 slots represent all the investments you can make in your lifetime. Under these rules, you would be limited to a finite set of opportunities and may be more compelled to think carefully about every investment you make.

Mistake #2: Buy High, Sell Low

Let’s set the stage by considering the success of Black Friday shopping. With the Christmas shopping season approaching, retailers mark down thousands of products over one weekend at the end of November. As a consumer, if you can purchase gifts at a lower price, why wouldn’t you do all your shopping when there are deep discounts? Economics 101 teaches us that when prices are low, demand grows, and as prices rise, demand declines. In short, people are generally motivated to purchase items when they are discounted, and sell or refrain from buying them when they believe they are fully or over-valued.

Unfortunately, this approach doesn’t always hold true in the investment world. It can actually be quite the opposite. High prices often attract investors, leading to higher demand, while low prices seem to scare people away.

Rational thinking would have us apply what we do on Black Friday to how we purchase stocks. Ideally, we buy stocks when we perceive that they are undervalued. We believe doing so increases our potential to achieve an attractive long-term return on investment. This is because we expect market prices to move upward to reflect the fundamentals of the underlying business.

While this might sound simple in theory, it is difficult in practice. Our brains are wired to be fearful of market declines and to be comfortable when markets advance. In difficult periods, be mindful of Warren Buffett’s advice to “be greedy when others are fearful, and fearful when others are greedy.”

How do we avoid the mistake of buying high, selling low?

Our recommendation: When you experience volatility in the markets, train your brain to consider whether anything has changed in the fundamentals of the companies in which you are invested or interested. Lower prices may mean good stocks are on sale.

Don’t panic in silence. If you are uncomfortable, discuss the news and market developments with a trusted advisor. Having a discussion with persons who can provide an objective and perhaps an experienced view will decrease the chances of jumping into or out of investments based on emotion.

Mistake #3: Trying to Time the Market

The goal of market timing is to be fully invested when markets are rising and safely out of them just before they begin to decline. To do this successfully, one has to be able to predict which way the stock market is going to move in the very short term. To make this prediction, people often rely on assessments of the economy, political developments, price charts or simply gut feel. A key challenge, however, is that our 24-hour global news feed generally sparks pessimism, which means it is not hard to find reasons to sell your stocks.

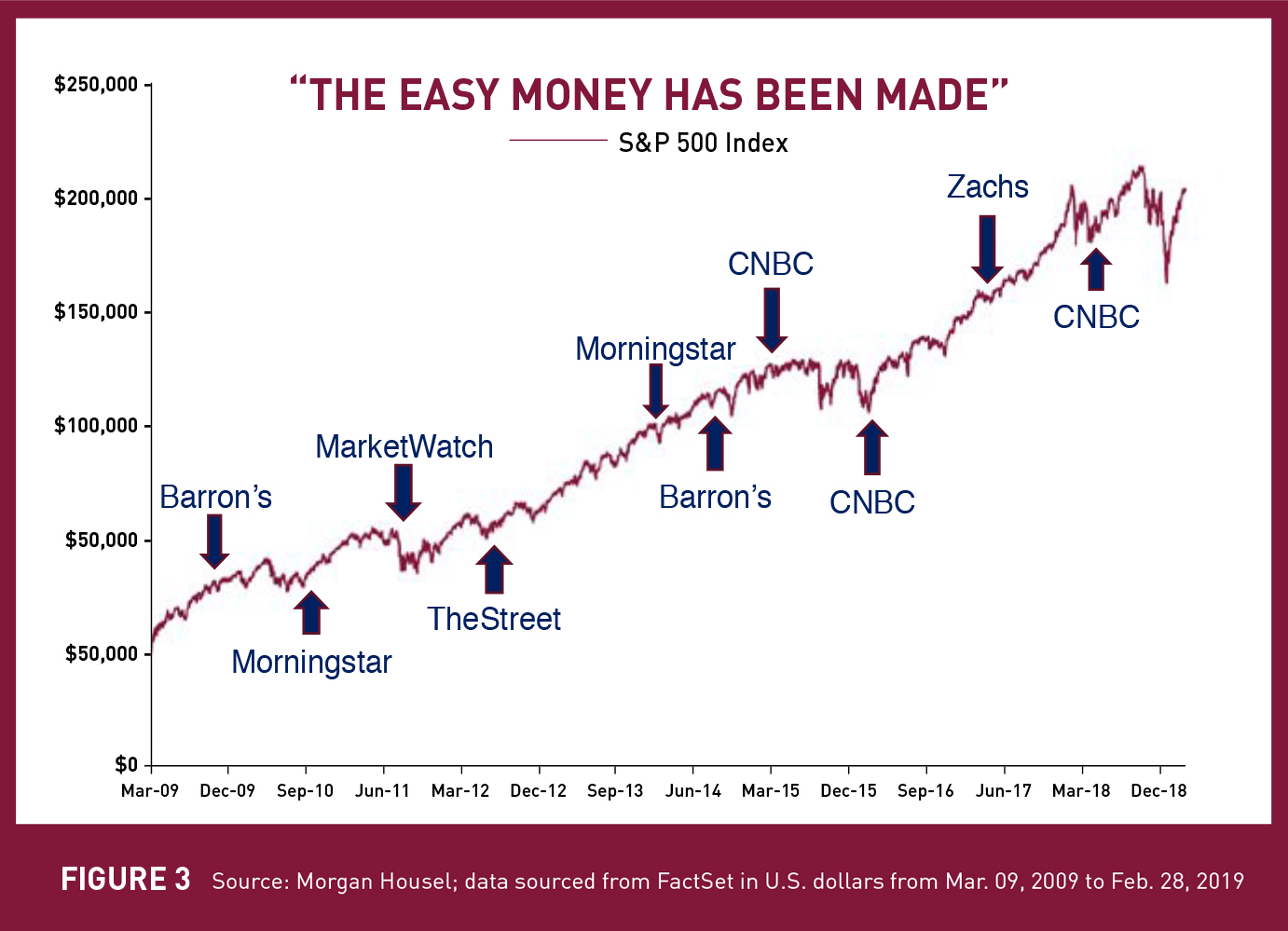

As an example, let’s look at a graph of the S&P 500 Index over the past market cycle, which began after the global financial crisis of 2007–2009. This cycle has been one of the longest recorded periods of stock market advances and a truly spectacular time to be invested. Paradoxically, financial experts were frequently quoted in the media as saying, “The easy money has been made”—suggesting that your investments had done very well and that it was likely a good time to sell (Figure 3).

In 2010, we had the Eurozone crisis and concerns that a number of European countries could not pay their debt. In 2011, the U.S. breached its debt ceiling and, as a result, U.S. government bonds were downgraded. In 2016, we had the beginning of Brexit.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that staying invested for the long term was the right approach during these volatile times.

Complex, adaptive systems

Why is it difficult to forecast short-term market outcomes? It is because markets are complex, adaptive systems that are fundamentally unpredictable.

Complex, adaptive systems are ones in which a perfect understanding of the individual parts does not automatically convey a perfect understanding of the whole system’s behaviour.

To illustrate, let us use the example of a traffic jam. Picture driving along a main highway when, abruptly, traffic slows ahead of you. You immediately slow down and so do those behind you. Within minutes, there is a traffic jam, causing agitation to many. The next group of drivers, a bit further behind, are alerted by their GPS systems to the traffic jam ahead and some divert to an alternate route. Before long, this alternate road is also jammed. There is a third group of drivers, much further behind. Do individuals in this third group choose to continue on the main highway or take their nearest exit? What do they think the other drivers are going to do? The actions of that third group of drivers are very difficult to predict.

Stock markets are similar. The behaviour of the system as a whole is difficult to predict because participants in the market are constantly acting based on their own set of objectives and predictions. The resultant interactions are generally impossible to foresee.

The cost of market timing

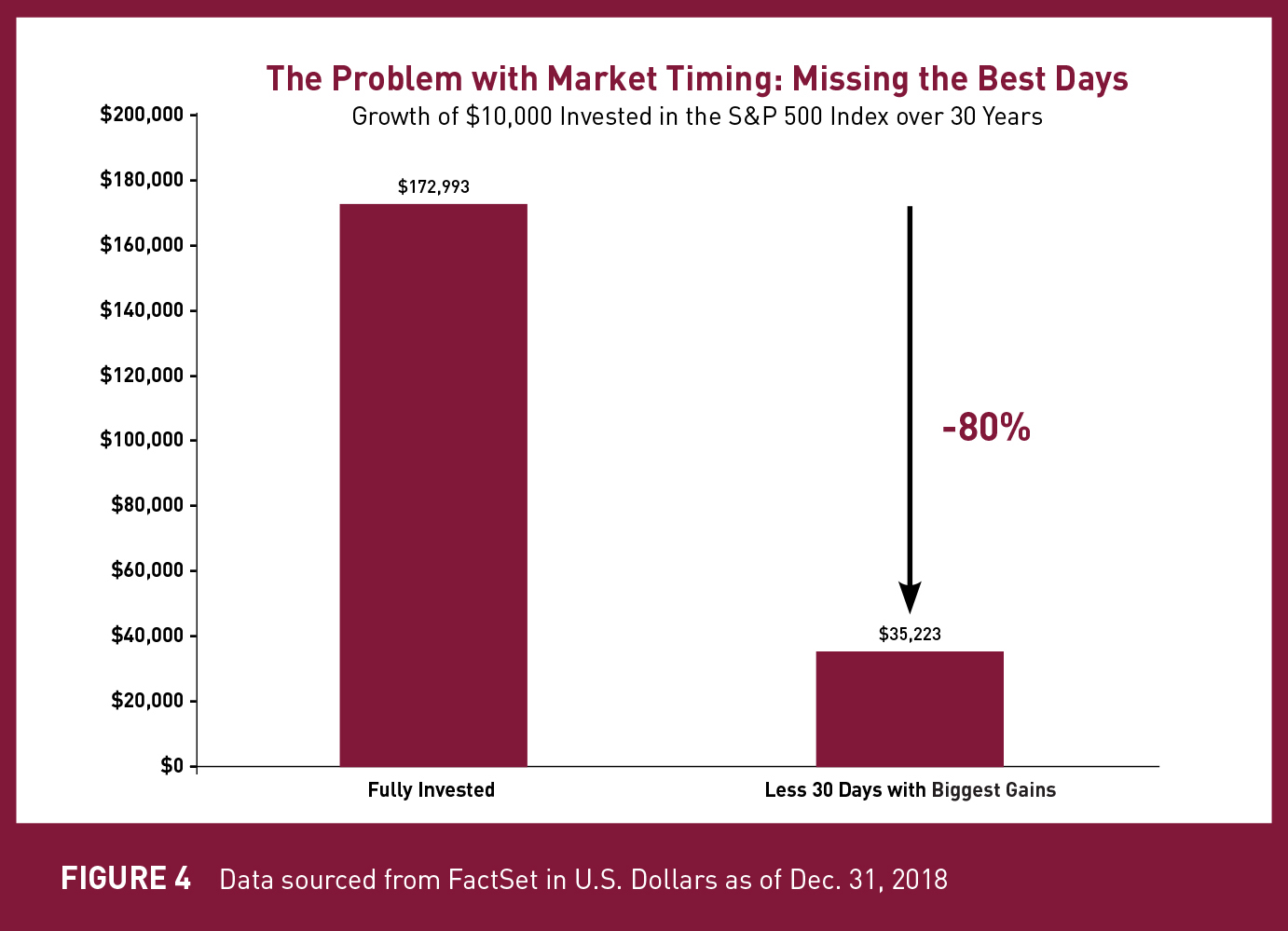

To time the market accurately, you need to know exactly when to sell but also exactly when to buy back in. The challenge is that significant market gains are often concentrated in just a few trading days each cycle. If you sell out of stocks in anticipation of a decline, you may miss some of the best performing days.

If you had invested in the S&P 500 Index for the last 30 years and done nothing else, your investment would have increased over 17-fold. Alternatively, if you had tried to time the market, selling your stock investments when you believed a decline was imminent, you might have missed some of the best performing days of that period. If you missed just the 30 best trading days— the equivalent of one day per year—it would have cost you 80% of your gains, cumulatively (Figure 4).

How do we avoid the mistake of trying to time the market?

Our recommendation: Recognize that predictions about the market are, at best, educated guesses; investors should ignore them.

Accept that volatility will happen. Have an investment strategy that you can stick to in all market conditions.

In the words of Nobel Laureate Eugene Fama, “Your money is like a bar of soap. The more you handle it, the less you’ll have.”

Sometimes, doing nothing is the best thing. It may seem counter-intuitive to do nothing, but applying an inversion lens will often determine this to be the best strategy for an investor, particularly one who applies value principals. Investing is a long-term endeavor and, like many things in life, requires patience.

Invert, always invert.

This publication is presented for illustrative and discussion purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment advice and does not consider unique objectives, constraints or financial needs. It is not intended as an offer to invest in any Burgundy investment strategies. Under no circumstances does this publication suggest that you should time the market in any way or make investment decisions based on the content. Select securities may be used as examples to illustrate Burgundy’s investment philosophy. Research used to formulate opinions was obtained from various sources and Burgundy does not guarantee its accuracy. Forward-looking statements are based on historical events and trends and may differ from actual results. Any inclusion of third-party books, articles and opinions does not imply Burgundy’s endorsement or affiliation. The information in this publication is as of the date of the publication and will not be revised or updated to reflect new events or circumstances.