One of the most frequently mentioned research studies in the field of developmental psychology is the “marshmallow test.” Conducted in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the experiment considered how children’s ability to exercise delayed gratification would affect their success in life. The test was designed like this: children were offered a single marshmallow by a researcher with the option of either eating it right away, or waiting approximately 15 minutes. If they could stave off temptation, they would receive two marshmallows instead of one. (If only compounding were always so easy.) After the experiment, the researchers maintained contact with the original children from the study. Over the course of several years, they took various measures of the success of the participants, including SAT scores and educational attainment. In a nutshell, the study found that children who chose to wait for the second marshmallow were more likely to have better life outcomes. We see a useful business lesson here: delayed gratification is a powerful force and foundational to success.

In our work as investment analysts, we see the marshmallow test at play across the business world. Every day, managers must decide whether to enjoy a dollar of profit this year or two dollars a few years from now.

Many of the things that are good for the long-term prospects of a business are not necessarily good for short-term profits. Forestalling price increases or making investments in the future, whether they are in the form of a new factory or a growing R&D staff, are not short-term profit maximizing activities. Nevertheless, they are often essential to the long-term success of a business. This makes investing a nuanced balancing act. As long-term investors, although we are attracted to highly profitable businesses, do we want our holdings to be maximizing profitability at all times? Might such an approach not lead towards short-termist, single-marshmallow managers rather than long-term thinkers?

“In our work as investment analysts, we see the marshmallow test at play across the business world. Every day, managers must decide whether to enjoy a dollar of profit this year or two dollars a few years from now.”

A business’s profit is only valuable insofar as that profit is sustainable, meaning that it can be protected and grown well into the future. That protection is provided by a moat, which insulates the business from competition and disruption. But like many good things, moats have a cost – one that well-run businesses willingly pay on a regular basis in order to protect their long-term sustainability. In this View from Burgundy, we will explore some of the ways that moats have a cost, and why that cost is both necessary and desirable despite limiting profitability in the short term. We will explore these costs across three dimensions: restrained usage of pricing power, moat-protecting expenses and moat-protecting investments. While all three can restrain short-term profitability, they serve to increase the sustainability and long-term value of a business.

RESTRAINED USAGE OF PRICING POWER

One important characteristic we look for in our investments is pricing power. The ability to raise prices says something clear about the value a business provides. Warren Buffett once put it best:

“The single most important decision in evaluating a business is pricing power. If you’ve got the power to raise prices without losing business to a competitor, you’ve got a very good business. And if you have to have a prayer session before raising the price by 10 percent, then you’ve got a terrible business.”1

While we agree with Buffett’s assessment of the importance of pricing power, we would add a caveat that this power must be used responsibly and with restraint.

As we will illustrate below with a cautionary tale, a business that overextends its pricing power can suffer for it in the long term.

Long-time Burgundy clients have likely heard us talk about the “razor and razor blade” business model. The term refers to the long-standing strategy of Gillette, the U.S. shaving products brand, in which razors are sold at a low price while razor blades are sold at a steep premium. The key to the idea is that once someone buys the razor, they are likely to continue buying the blades that match it. Historically, due to both the sunk cost of the razor and to consumer habit, Gillette was able to increase the prices of its razor blades with little fear of losing its customers – something it exercised on a regular basis. This strategy helped Gillette build a grooming empire. It was widely celebrated as a model example of pricing power in the consumer staples industry, and Gillette was acquired by Procter & Gamble (P&G) in 2005 for US$57 billion.

We have always liked “razor and razor blade” businesses, which are not confined to just the consumer products industry but can in fact be observed throughout a wide range of industries. Overall, what investors like about this model is that it offers a high level of recurring profitability for owners of the business: once a customer has purchased the razor, the future purchases of razor blades are highly predictable.

But are they still highly predictable if prices continually rise? Let’s look at how Gillette has fared in recent years.

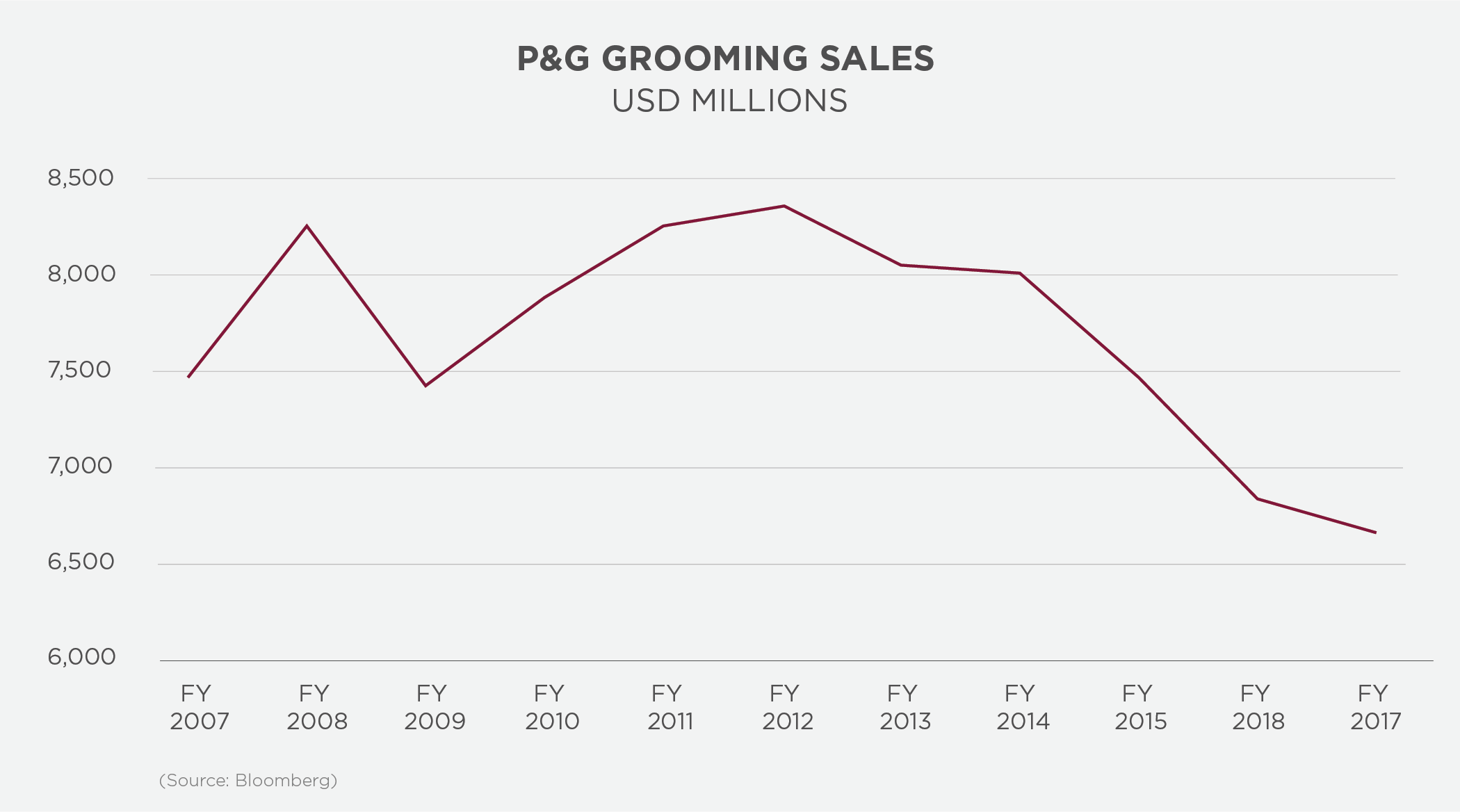

As the above chart indicates, not all is well at the original “razor and razor blade” business. In the last five years, P&G’s Grooming division (which is made up mostly of the former Gillette business) has seen revenues fall by a fifth. Why is this?

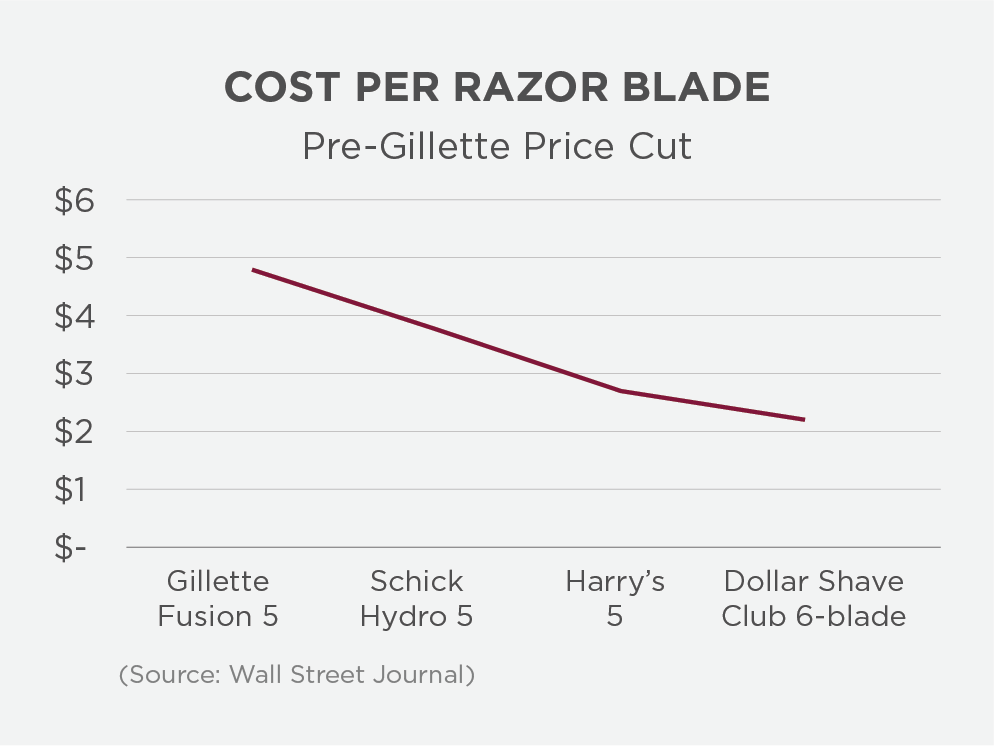

It turns out that while Gillette was busy gorging itself on short-term marshmallows, its price increases created an environment in which new competitors were growing and thriving. Over the last decade, online shaving subscription clubs, such as Harry’s and Dollar Shave Club, emerged. They began to take Gillette’s market share by offering razors at much lower price points – so low that as of 2017, Gillette’s competitors were selling comparable razors from 22% to 54% cheaper for a similar product! It might not come as a surprise, then, that in the same year P&G’s U.S. sales of razor blades were down 18%, or that the company was eventually forced to cut prices up to 20% for some of its most popular razors last year. In so doing, years of price increases were reversed in order to stem the loss of customers.

In the case of Gillette we can see that the overuse of pricing power, while beneficial for profitability in the short term, drove customers away and invited hungry new competitors. The sustainability of its business has been weakened as a result, and time will tell whether its drastic 2017 price cut can reverse the damage that has been done to the Gillette business.

Not all businesses that possess pricing power always make full use of it. Given the competitive and deflationary environment in Japan, we have seen cases in which strong businesses forego exercising their pricing power, choosing to grow profits via other means.

Consider the example of Otsuka Shokai, a Japanese IT system integrator that sells to and services small business clients. Otsuka’s main competitors, such as Fujitsu, are giants that cater to the needs of Japan’s largest corporations. In contrast, Otsuka’s customers are rather tiny, with more than half its client base having annual sales of less than US$100 million. The key element of its business model is that Otsuka is structured in a way that allows it to profitably sell to (and service) these small clients, whereas its larger competitors cannot do so profitably and thus ignore the small business segment of the market altogether. As a result, Otsuka faces very little direct competition in its niche.

Otsuka’s small business customers are sorely lacking in internal IT resources and often rely entirely on Otsuka for their hardware, software and maintenance needs. This puts Otsuka in a strong bargaining position. Yet as the company has grown, gross profitability has not increased much despite it enjoying scale-based cost savings on the purchasing side. With that in mind, in our first meeting with the company, we perplexedly asked what was going on: “Are you passing on the cost savings to your customers? Why not maintain prices so that you enjoy the benefits from your cost savings that come with growing economies of scale, or even raise prices a little bit?” The director we were meeting calmly brought our attention to the last slide in their investor presentation titled “We Live Up to Our Stakeholders’ Confidence,” pointing out the “Customers” segment in particular.

The message: we look after our customers.

Our first reaction was not positive: Was this a for-profit enterprise that treated shareholders equitably alongside its other important stakeholders, or were we merely an afterthought?

After further analysis and subsequent meetings with the company, we have become a bit less critical of their approach. Here is a business that is differentiated from its competitors, has a great reputation, and which has customers that rely upon it for their IT operations. We believe it possesses pricing power, but forgoes price increases. Keeping in mind the example of Gillette, are we so sure that this is unwise? Perhaps Otsuka’s restraint around pricing has actually helped to protect its moat. Otsuka is able to not only enjoy the growth in IT spending among its existing small business clients, but can also grow its customer base. Raising prices can invite competition and new entrants, and Otsuka’s strategy has avoided inviting such threats. With that in mind, the company has been able to grow profits healthily, at a 14% compound rate over the last five years – not through margin expansion, but by growing its customer base and by increasing its share of wallet with existing customers. Importantly, its profit growth has not introduced new threats to the business. While pricing power is perhaps one of the most indicative elements of a business’s competitive strength, foregoing – or at least responsibly using – that power in the name of maintaining a commanding competitive lead is another example of how some businesses can give up a bit of short-term profit in the name of a much more secure stream of long-term profit. Another example a bit closer to home is Amazon, a company whose entire strategy revolves around foregoing profitability in order to win customers, grow sales, crush competitors and pressure suppliers. Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s CEO, was famously quoted saying “Your margin is my opportunity.” While we prefer to own profitable businesses, in the current business environment full of disruptive threats like Amazon, pushing pricing power to its very limit (or beyond) can prove to be self-destructive.

“While pricing power is perhaps one of the most indicative elements of a business’s competitive strength, foregoing – or at least responsibly using – that power in the name of maintaining a commanding competitive lead is another example of how some businesses can give up a bit of short-term profit in the name of a much more secure stream of long-term profit.”

MOAT-PROTECTING EXPENSES

Many of the businesses we own have to spend money on a regular basis in order to maintain their moat. This investment commonly comes in a few different forms. Perhaps one of the most common ones is research and development (R&D), which is a significant expense that is often above 2% of sales and can be much higher in high-tech businesses. For instance, Google spends a whopping 15% of sales on R&D, amounting to US$16 billion in the last fiscal year alone. Given that this is a cash outflow, how should we view R&D expenses? Is this something we’d like minimized so that shareholders can be enriched?

The reality is that R&D is often a necessary expense that in many cases reinforces a business’s moat. This spending is dedicated to improving existing products and services, developing new ones for future growth, and improving internal processes that can reduce costs and improve efficiency – all of which help a business stay competitive and ward off ever-hungry competitors. At Burgundy, we often find R&D spending to be critically important to creating or maintaining product differentiation, which can be a source of competitive advantage. As a result our holdings tend to dedicate a significant amount of sales to this crucial expense.

Another area in which businesses protect their moats at the cost of higher recurring expenses is in providing excellent sales and servicing. While the associated employees can be a significant recurring cost, they can also contribute to a significant competitive advantage. Hoshizaki, Japan’s largest manufacturer of foodservice equipment and a Dream Team name2 in Asia, provides a good example of this.

Hoshizaki is a titan in the Japanese foodservice equipment industry. Across its main products, which include ice makers, refrigerators, dishwashers and beer dispensers, the company boasts leading domestic market shares that range by product (from as low as 35% to as high as 70%). The key factor to its success in the Japanese market is that Hoshizaki employs a unique business model in which it does direct sales and servicing. This is in contrast to the industry standard approach where equipment is sold into a fragmented network of independent dealerships, which then re-sell the products to the end users, such as restaurants. The advantages of Hoshizaki’s direct sales model are significant. Through direct contact with its end customers, Hoshizaki is better able to understand their needs, which makes its salespeople more effective at selling equipment and addressing the needs of customers. What’s more, by providing equipment servicing with its own employees, it has built a stellar reputation for taking care of its customers. Finally, these service engineers also play a key role in generating new equipment sales. According to the company’s president, 70% of sales are traceable to a Hoshizaki service person pointing something out to the customer, whether it is the need for another repair, an upgrade or a piece of new equipment altogether. Combined, these advantages have placed Hoshizaki firmly at the top of its industry in Japan.

Of course, providing personalized sales and rapid response service to Japan’s 600,000+ restaurants and a host of other customers (hotels, schools, retirement homes, etc.) has a cost. In its Japanese business, Hoshizaki employs 3,100 sales staff and 2,500 maintenance engineers across 447 sales offices in order to maintain so many touchpoints. This is a detractor on the firm’s profitability, which we can see in the company’s regional differences in profitability. Its operating margins are lower in Japan (13%) than in the U.S. (16%),3 where Hoshizaki sells its products through dealers due to the logistical difficulty of profitably running a direct sales model in a country so geographically large. As a result, there are fewer Hoshizaki mouths to feed in the U.S. and the resulting operating expenses are lower.

The important question to ask here is this: all other things being equal,4 would we rather own the higher margin U.S. business or the slightly lower margin Japanese one? The answer is the latter. Although it comes at a cost, Hoshizaki’s Japanese business is more sustainable and less likely to be disrupted. Its knowledge of its customers, said customers’ almost total reliance on Hoshizaki, and its stellar brand lead us to believe that the risk of disruption in Japan is extremely low. This gives us a great deal of confidence in its ability to maintain its profitability well into the future and continue to enjoy the lion’s share of market growth there. In other words, Hoshizaki favours slightly fewer marshmallows today in exchange for many more in the future.

MOAT-PROTECTING INVESTMENTS

While the two examples above directly impact a company’s income statement by reducing margins, the cost of maintaining or growing a moat can come in the form of large investments. Whether by way of capital investment or M&A, sometimes strong businesses must make capital outlays in order to maintain or improve their competitive position. While the upfront cost can be large, the potential long-term benefits of maintaining competitive advantage in a growing industry can be enormous.

Take the example of San-A Corporation, a holding in the Asian Equity strategy that is based in the Japanese prefecture of Okinawa, an idyllic semi-tropical island of 1.4 million people located about 1,500 kilometers south from Tokyo. San-A operates the largest chain of grocery and general merchandise stores in Okinawa and also owns and operates shopping malls. It is the largest company in the prefecture by revenue, and it has a dominant position in the Okinawan retailing industry due to local economies of scale, in-house logistics expertise, and a deep understanding of local consumer tastes.

Okinawa is a very popular destination for regional inbound tourism and has experienced significant growth in foreign tourist arrivals. Weather aside, one reason for the island’s popularity is its favourable proximity to the increasingly wealthy populations of many Asian city centres: it is only a two hour flight from Shanghai or Seoul, a three hour flight from Beijing or Hong Kong, and only 90 minutes away from Taipei. Today, roughly nine million tourists fly to Okinawa every year, roughly in line with that of Hawaii. Tourists from overseas account for only 2.5 million of these visitors today but have grown an astonishing seven-fold, or on average of 47% per year over the last five years!

Faced with this massive growth in inbound tourism, San-A has decided to invest in its future growth by building a new shopping mall designed to cater to Okinawa’s growing international tourist base. This is a significant undertaking, as the new mall is 60% larger than San-A’s current largest facility and would become the largest shopping mall on the island. Of course, San-A’s investment in this project requires a sizable upfront investment of 47 billion yen (US$427 million), which will have a negative short-term impact on San-A’s profitability due to rising depreciation costs associated with the project. As investors, rather than lament this, we are eager for our holdings to make investments that will produce healthy returns over the long term. In the case of San-A, we see an aggressive but well-thought-out growth strategy that will help it maintain its dominant position in Okinawan retailing while growing its exposure to the island’s booming tourism. (Best of all, the project is self-financed due to San-A’s fortress balance sheet.) This is another instance of behaviour designed to grow profits long into the future at the cost of some profits today – a great example of long-term marshmallow maximization.

In our view, some of the leaders in the U.S. technology space provide excellent examples of investing to protect a moat. Consider the example of Google, a holding in our American Equities strategy. The company owns the world’s dominant search engine, which boasts 75% global market share in desktop search and 87% global market share in mobile search. Its search engine processes 63,000 searches per second (roughly two trillion searches per year), which combined with a self-improving algorithm further improves its functionality over time. The company’s moat comes from consumer habit and the fact that its leadership position in search reinforces itself by improving the algorithm on a daily basis. Google’s dominance in search has allowed it to build an online advertising empire that in 2017 earned over US$95 billion.

Google has made a number of key acquisitions that have allowed it to protect its moat over time. The first of these was the acquisition made in 2005 to address the looming threat of internet activity shifting from desktops to mobile phones. As Google recognized that consumer behaviour was changing, the company maintained its leadership in search by buying Android, the largest provider of mobile phone operating systems today. Google was right to be wary of the mobile threat. Today, the company’s search mix has transitioned from 100% desktop in 2007 to a mix closer to 60% mobile and 40% desktop. Remarkably, in hindsight we can say that the rumoured US$50 million spent on Android was obviously an incredibly well-timed acquisition, as it allowed Google to keep its moat in search. But given the value of the search business today, it is clear that even at a price orders of magnitude higher, it would have been worth preserving Google’s immensely valuable moat.

CONCLUSION

At Burgundy, our work as quality investors is not as simple as identifying businesses with stellar economics – that is just the first step, and the easiest. Our assessment of the long-term value of a business concentrates heavily on whether those economics can be maintained, and this is where our attention on the moat comes into play. While we are always focused on threats to the profitability of a business, we welcome prudent decisions by managers to improve a business’s long-term viability, whether they are in the form of responsible pricing strategies, moat-building expenses or moat-building investments. While these decisions bear a cost in the short term, we know that delayed gratification reaps rewards in the future. In other words, we’ll happily wait our 15 minutes.

1. “Warren Buffett: There’s Only One Thing That Matters To Me When I’m Investing In A Company”

2. A Dream Team company is one that meets Burgundy’s assessment of quality but whose valuation does not warrant an investment. We monitor these companies, waiting for the right purchase price

3. This is partially due to product mix but also partially due to the overhead costs in Japan

4. Including growth, though importantly Hoshizaki’s Japan business is indeed growing

This View from Burgundy is presented for illustrative and discussion purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment advice and does not consider unique objectives, constraints, or financial needs. Under no circumstances does this View from Burgundy suggest that you should time the market in any way or make investment decisions based on the content. Select securities may be used as examples to illustrate Burgundy’s investment philosophy. Burgundy portfolios may or may not hold such securities for the whole demonstrated period. Investors are advised that their investments are not guaranteed, their values change frequently, and past performance may not be repeated. This View from Burgundy is not intended as an offer to invest in any investment strategy presented by Burgundy. The information contained in this post is the opinion of Burgundy Asset Management and/or its employees as of the date of publishing and is subject to change without notice. Please refer to the Legal section of Burgundy’s website for additional information.