In a world that begs we take a consensus view, taking the road less travelled can be an uncomfortable choice socially and spiritually. In this View from Burgundy, Portfolio Manager David Vanderwood attempts to answer how to be a contrarian by investigating the rewards and challenges of taking an investment approach that defies the status quo.

KEY POINTS

- If you want to be a successful contrarian, be prepared to look wrong in the short term.

- Being disagreeable is non-negotiable if one is to withstand the inherent social pressure that is out there.

- Contrarian investing pays but is not easy.

- Human nature does not change.

One of our investment interns recently asked me how to be a contrarian investor. I did not have a good answer, and I could see the disappointment on his face as he left my office. In this View from Burgundy, I will attempt to right this wrong. First, by exploring the rewards and challenges of being a contrarian investor. Next, by identifying the personality traits that help. And finally, by examining both how and when to identify successful investments that defy the status quo.

BECAUSE IT PAYS

A contrarian investor will purposefully go against prevailing market sentiment by buying when others are selling and selling when others are buying. Why would anyone want to do this? Because it pays.

Stock prices tend to overshoot, on the upside and on the downside, leading to investment opportunities. A successful contrarian can buy attractive stocks when they are trading for well under intrinsic value. This is a recipe for earning excess returns.

If it pays to be a contrarian, how come more people are not pursuing this approach? Because it is hard. Humans evolved in groups, so we pursue something called social proof. This means conforming so we can be liked and accepted by the group. Standing apart from the crowd goes against the grain, and that can be lonely and difficult. Now that we understand the why, let us discuss how to be a successful contrarian investor.

“To be a successful contrarian, you must be prepared to look wrong in the short term.”

A TEST OF CHARACTER

To be a successful contrarian, you must be prepared to look wrong in the short term. The collective response over the life of a successful contrarian investment is, “You’re wrong. You’re wrong. You’re wrong,” until finally, “You’re right.” Living within the days, weeks, months, or even years before your investment thesis proves correct when others think you are wrong is not for the faint of heart. Thick skin is needed. That is why investing is not a test of intelligence, but a test of character.

And this character will be tested. There are significant potential downsides to being a contrarian if you are wrong (or even if you are eventually right, but too early). Being contrarian at the beginning of a career can put that very career at risk. Since you may get fired during the “You’re wrong” responses, even if the thesis eventually plays out correctly, most choose to play it safe. Jeremy Grantham, Co-Founder of investment firm GMO LLC, once wrote that the “central truth of the investment business is that investment behaviour is driven by career risk.” i

An investment firm takes on business risk by supporting contrarian ideas for the same reason. When the inevitable happens and a firm’s contrarian investments take longer than expected to play out, clients often fire the investment manager. That is why most investment firms are businesses – marketing organizations focused on gathering assets and fees – rather than professions where intelligent investing comes first. They have learned that mediocrity pays, but only for the firm’s owners and never the clients.

Running an investment firm as a profession and striving to generate maximum real returns for clients means taking on individual career risk and collective business risk. These are the prices paid to earn the excess returns promised by a successful contrarian approach. There is no free lunch. A long-term, patient, and independent investment partnership acting as a profession is an ideal structure to allow the time for contrarian bets to play out and add real value.

Ideally, an investment firm run as a profession has clients that share the same values and are willing to take the contrarian journey along with the investment manager. Clients that support a patient, long-term investment approach that stands apart from the crowd underwrite the time for contrarian theses to play out. Morgan Housel described the emotional and temporal support managers can receive from clients in The Psychology of Money: “Having a gap between what you can technically endure versus what’s emotionally possible is an overlooked version of margin of safety.”ii

DISAGREEABLE PERSONALITY

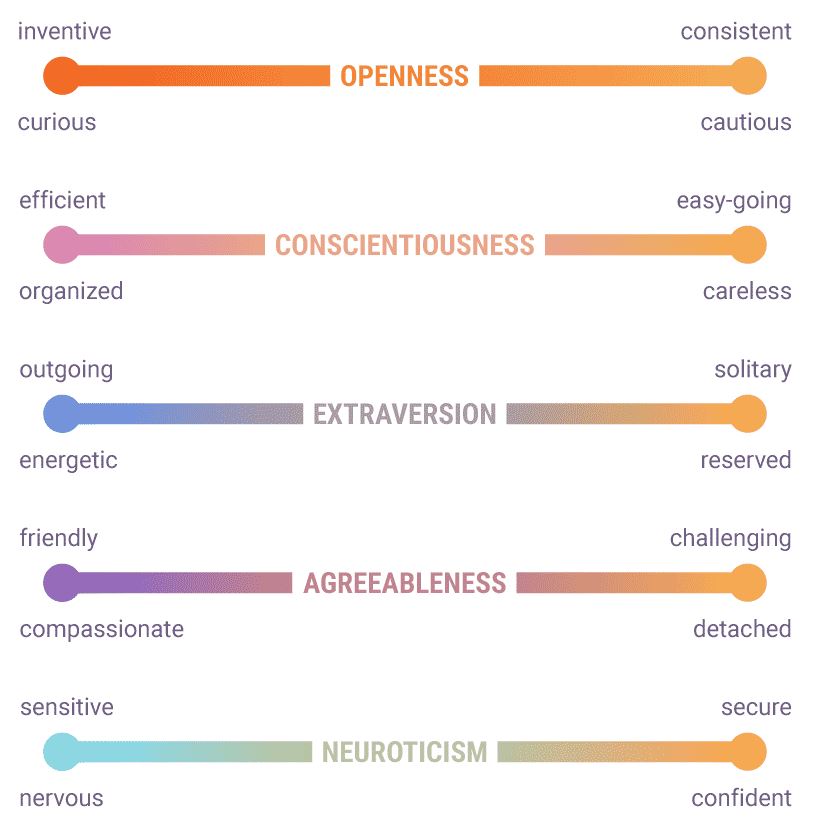

To be contrarian, it helps to have a specific personality type. According to the most widely used personality model, the Big Five Personality Traits (see Figure 1), each of us falls onto a continuum of five characteristics: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism, and most psychologists feel that our individual traits remain stable over time. While it surely helps if an investor is introverted (to love studying businesses and reading history), open (to be curious), neurotic (to constantly worry that something in the analysis has been missed), and conscientious (to be well organized and aware), being disagreeable is non-negotiable if one is to withstand the inherent social pressure that is out there.

FIGURE 1: THE BIG FIVE PRINCIPLE

Copyright Adioma

Disagreeable people tend to want to challenge conventional wisdom. They find it easier to be detached from popular opinion. Both traits are necessary if one is to be a successful contrarian investor. This personality type has an easier time hearing the repeated calls of “you’re wrong” until the investment thesis pays off. Indeed, given the immense pressure, it may be a necessary pre-condition for a contrarian to have a disagreeable personality.

TIMING IS EVERYTHING

Critically, one must successfully identify when to be a contrarian. As I learned the hard way very early in my contrarian career, the consensus is usually right. So being contrarian just for the sake of being contrarian is a costly approach. It takes a tremendous conceit to conclude that everyone else is wrong about an investment. But sometimes they are. This is where it pays to act contrarian.

“It takes a tremendous conceit to conclude that everyone else is wrong about an investment. But sometimes they are. This is where it pays to act contrarian.”

To be successful, one must be able to identify the rare times when the consensus is wrong. This takes an appreciation of the appropriate historical context, a thorough understanding of long-term business economics, as well as an ability to recognize when contradictions are inherent in the consensus point of view. Once identified, great patience is usually called for. As the identified contradictions eventually unfurl, the contrarian investment thesis will play out successfully.

Picking the exact timing is impossible, which makes contrarian investing especially difficult. Even if full of contradictions, the status quo underlying a popular consensus view often lasts far longer than you think possible. But fortunately, it also often changes quickly and dramatically when it does finally change.

CONTRARIAN CASE STUDIES

Now, let’s take a deeper dive into how a contrarian investment approach can be successful using a company example from the Burgundy Canadian equity portfolios.

We have made two successful contrarian investments in grocer Loblaw Companies Ltd. In 2009, Loblaw became the largest holding in our Canadian equity portfolio. The company was in the midst of a major systems integration, necessary after many years of acquisitions left the grocer with an unwieldy mix of different merchandising, warehouse, and transportation management systems. The integration was not going smoothly. What was to be a two-year project turned into a five-year fiasco that left shelves empty and customers angry. Our research concluded that this problem would be solved and so we made an investment. As often happens, we were early and had to endure hearing “you’re wrong” for a few years before we ended up being right. Eventually our thesis played out and Loblaw’s share price went on to double over the next five years. While three years of being “wrong” can be difficult, we had conviction in our research, and we responded to the share price weakness by doubling down on our research and buying more shares. It paid to be a contrarian.

When we re-acquired Loblaw in 2018, the contrarian call was different. Amazon announced the acquisition of Whole Foods that same year, leading to a 15% drop in Loblaw’s share price as investors fretted about the impact of this technology leader attacking Canada’s grocery industry. We viewed this as a contrarian opportunity. Whole Foods had only 12 Canadian stores at the time, compared to over 1,000 for Loblaw, and we felt that this competitive threat would be very manageable. It reminded us of Costco entering the Canadian industry in 1993 and Wal-Mart in 1994. After some machinations in the mid-nineties, Canada’s grocery industry remained a profitable oligopoly dominated by the Big Three: Loblaw, Metro, and Empire (Sobeys). Similarly, we thought this profitable structure would be maintained after Amazon acquired Whole Foods. It was, and with Loblaw’s share price doubling in less than four years, our contrarian investment paid off again.

CONSTRUCTING PORTFOLIOS

While the case studies above are two successful examples, as discussed, this is not always the case, or at least not always immediately. When the “you’re wrong” responses seem correct and last for years, career and business risks can be realized well before the investment turns into a success. Having the right portfolio structure helps mitigate this risk.

Since the sizing of positions is critical, a successful contrarian will pay close attention to portfolio construction. When making an initial investment, care must be taken to leave room to buy more if, as often happens, the stock price drifts sideways for extended periods of time, or even lower, if the contradictions inherent in the thesis take longer than expected to play out. As famed investor Bill Miller once said, one needs to average down because in the long run, the “lowest average cost wins.”

The right portfolio structure also means maintaining adequate diversification by idea “type.” The aim is to avoid having too many eggs in one idea basket. I have also learned this lesson the hard way. With an adequately diversified portfolio, enough of the former contrarian ideas play out successfully in the market, compensating for the ones still stuck in the “you’re wrong” waiting period, such that the overall portfolio return is solid.

“The right portfolio structure also means maintaining adequate diversification by idea “type.” The aim is to avoid having too many eggs in one idea basket.”

THE HEDGEHOG AND THE FOX

If the market is usually right, how can one become better at identifying those rare successful contrarian investments? By becoming a hedgehog and a fox.

In his popular essay, “The Hedgehog and the Fox,” philosopher and historian Isaiah Berlin divided thinkers into two categories. Berlin believed Plato and Nietzsche were hedgehogs, ones who view the world through the lens of one defining idea, and Aristotle and Shakespeare were foxes, ones who draw from a wide variety of perspectives.

Value Investors are Hedgehogs

Value investors find it comforting to think of themselves as hedgehogs with “intrinsic value” – one’s estimate of what a company is worth – the single lens to view the investment world. And while this is a good place to start, it is not enough. Focusing only on intrinsic value, like a good hedgehog, may have worked in the past, but things have changed.

Change is accelerating, both in our daily lives and in business. With the expansion of disruption and competition stemming from the globalization and digitization of commerce, there has been an increasing turnover of companies’ fortunes. According to McKinsey, the management consulting company, the median age of the top-10 companies in the S&P 500 Index has fallen from 85 years in the year 2000 to just 30 years today. Spanning the entire index, the average age of member companies is now under 20 years. Many companies have seen their intrinsic value erode in the face of this quickening change and disruption. It only takes a few so-called “value traps” in one’s portfolio – cheap companies where value erodes after investment purchase – to destroy overall portfolio wealth. This helps explain why pure “value” investment strategies have underperformed since 2007 and why it is not enough to be a good value hedgehog.

Being a Fox too

Being a value hedgehog and having “intrinsic value” as your only compass is not enough. A successful contrarian must also be a fox. John Lewis Gaddis, the Professor of Military and Naval History at Yale University who published On Grand Strategyiii in 2018, uses the hedgehog and the fox metaphor to decipher optimal military strategy. While not unsympathetic to the strengths of military hedgehogs, Gaddis argues persuasively that the best military strategists are foxes. He defines a fox as one who maintains “situational awareness,” meaning one who anticipates change.

Applied to investing, a fox maintaining situational awareness asks what is changing that could impact a given company’s intrinsic value, what could change in the future, and what the unknown unknowns are.

A fox also listens to feedback in maintaining situational awareness. In the case of successful contrarian investors, this especially includes taking note of changing stock prices. It is critical to discern whether a declining share price simply represents the collective opinion of a consensus made in error – hence an opportunity – or a decline in intrinsic value because business economics have been, or will be, impaired. This takes a lot of independent research and thought. Being able to discern which is correct is key to whether a potential investment is a value trap or a possible successful contrarian investment.

What about Burgundy?

How does contrarianism tie into Burgundy’s investment approach? At our 2022 Burgundy Forum, Co-Founders Tony Arrell and Richard Rooney shared that contrarianism has always been baked into Burgundy’s approach and that this stance usually involves being able to put up with some rough weather. We do so by allowing ourselves to be foxes that are able to discern quality as well as hedgehogs with a strong sense of direction pointing to intrinsic value. This confluence is what makes up Burgundy’s quality/value approach. Burgundy often takes a subtle contrarian route. We avoid investing in popular stocks when the consensus opinion is that they are “sure things.” Looking back a year ago, these would include highly valued technology and speculative stocks. Today, we are steering clear of many commodity companies. By avoiding potential capital losses when market or sector bubbles are popped or sentiment comes back to earth, a contrarian approach can help preserve capital.

Being a Contrarian

FINAL THOUGHTS

Contrarian investing pays but is not easy. At Burgundy, we take steps to make it work. We structure our firm like a profession and seek out aligned clients to join us on the contrarian journey. We take steps to optimize our portfolio construction, both with initial position sizing to leave room for averaging down and through adequate diversification.

When it comes to identifying successful contrarian investments, we seek contradictions inherent in consensus opinion and recognize that effective contrarians must develop the ability to combine the fox’s discernment of quality with the hedgehog’s sense of direction.

Change may be accelerating, but one thing doesn’t change. Human nature. As the 18th century French philosopher Voltaire once said, “History never repeats itself. Man always does.” Since there will always be cycles of fear and greed and associated market overreactions, there will always be potential contrarian opportunities. In the rare case where a suitable contrarian opportunity is identified, being a disagreeable personality type may be a necessary pre-condition for riding out the calls of “you’re wrong” until the thesis plays out. Investing, and especially contrarian investing, is a test of character. Thick skin will surely follow.

So, the next time an intern asks me how to be a successful contrarian investor, I will have a better answer.

i. Grantham, Jeremy, April 18, 2012, My Sister’s Pension Assets and Agency Problems, GMO.com

ii. Housel, Morgan, 2020, The Psychology of Money, Petersfield, Harriman House

iii. Gaddis, John Lewis, 2018, On Grand Strategy, New York, Penguin Press

This View from Burgundy is presented for illustrative and discussion purposes only. It is not intended to provide investment advice and does not consider unique objectives, constraints, or financial needs. Under no circumstances does this View from Burgundy suggest that you should time the market in any way or make investment decisions based on the content. Select securities may be used as examples to illustrate Burgundy’s investment philosophy. Burgundy portfolios may or may not hold such securities for the whole demonstrated period. Investors are advised that their investments are not guaranteed, their values change frequently, and past performance may not be repeated. This View from Burgundy is not intended as an offer to invest in any investment strategy presented by Burgundy. The information contained in this post is the opinion of Burgundy Asset Management and/or its employees as of the date of publishing and is subject to change without notice. Please refer to the Legal section of Burgundy’s website for additional information.